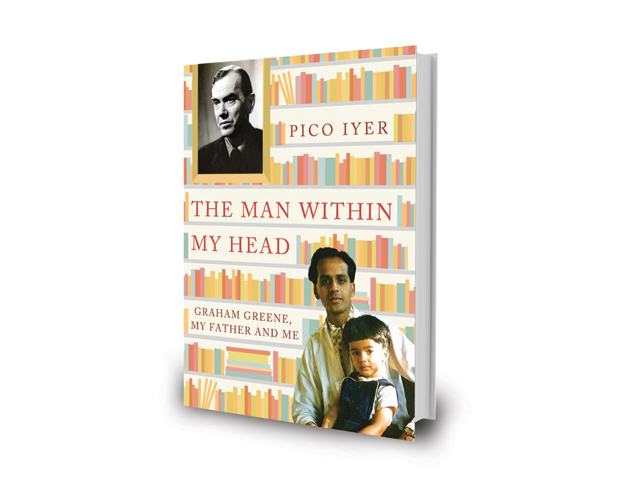

It is winter in Thimphu, Bhutan. Pico Iyer is reading his favorite author, Graham Greene. It is something he has done several times over the decades since he first read Greene as a schoolboy. But then, suddenly, he has a strange feeling. Iyer feels as if he is “on the inside of the book, a spotlight trained on something deep inside me. Whatever questions the story was posing to Brown [a character in the book], about where he stood and what he’d do, it seemed to be posing to me.” Suddenly, the lights go out. There are no candles in the room, no matches. He moves to the only light in the room – the two orange rods of the gas heater – and begins to read. Iyer finishes reading, his heart thumping at what has just happened. To calm down – or to make sense of what had possessed him – he begins to write “a confession and an essay.” The next day he posts his six-page letter to Graham Greene, in Antibes, France.

Not an extraordinary incident—certainly not when we think of some of the events that Iyer has given us in his travel pieces. But what makes it strange is the fact that Iyer has never met Greene. But Iyer’s letter is not a letter to a stranger; on the contrary, it is to a confidant. Iyer repeatedly stresses in the book that “knowing” someone is not always about knowing them in person, and that there are sides to a person that not even their closest relations or friends know, or understand, a side that is best known, inexplicably, to an outsider. Greene is that outsider in Iyer’s life, although he has taken up permanent residence in the latter’s head. Iyer feels that Greene understands him better than anyone else, and he in turn gets from Greene’s books things that other readers never see. It is as though the route to his core passes through Greene’s works: Greene’s shadow illumines Iyer’s inner corners.

Fans of Iyer’s work, especially his nonfiction, needn’t worry about the book being a fan’s homage to his literary idol. It is a masterly weaving of Iyer’s life, from his childhood to his schooldays in Oxford to his Ecstasy-inspired love affair. A few pages are devoted to tracing Greene’s life, and he also goes back to his own father’s life. He also draws from his nearly three decades of traveling and travel writing, presenting amusing and moving tales of adventure, misadventures, spooky places and shady characters (too much like a Greene novel, he would say). But he uses these to ultimately highlight a point Greene had made decades ago in some book.

The Man Within My Head is an outpouring of the author’s impressions and insights into one of the most famous novelists of the twentieth-century, a long conversation that a man has kept having with himself (Iyer never got to meet Greene; his written request for an interview, when Greene was eighty-five, was politely turned down by the novelist). It is like a revised, longer version of the letter he dashed off to Greene. Because it comes from the depths of privacy, the book’s contents – Iyer’s confessions, Greene’s doubts – strike a chord with the part of us that carries certain thoughts locked in our heads, thoughts we want to share, if only to better understand ourselves through them. The book, with its elegant style and probing content, is likely to remain within the heads of readers for some time.