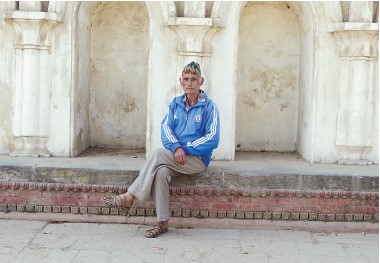

Tall and upright, he walks in fast, brisk steps. With the energy he displays, it is hard to believe that this man is 81 years old. A secret to his healthy old age? He says it’s the daily diet of fresh, pure milk and dairy products he grew up with.

“It was common for every household to own one or two cows,” he says. “After finishing the daily morning routine, the first thing my father did was to head to the cowshed with his milk bucket and milk the cows.”

Every household extracted its own ghee and mohi (skimmed milk) and fermented curd, and along with milk, these were parts of the everyday meals for people from Khanal’s generation. “Perhaps, I might have drank more milk and mohi than water in my life,” he tells me, suggesting the huge quantity of these products his generation consumed growing up.

As I talked to Khanal, who sat cross-legged opposite me by the banks of the Bagmati River in Sankhamul, I felt as if he was echoing what my father had been telling me for many years. For, whenever I ask my father, born 25 years after Khanal, to tell me how things were when he was younger, one of the favorite things he likes to repeat is the abundance of pure milk and dairy products he enjoyed growing up and into his early adulthood.

The meals he ate growing up in Lamatar, a village to the south of Lalitpur, was no different from Khanal's, especially when it came to consumption of dairy products.

Kathmandu Valley was still largely a pastoral place at the time when my father was growing up, and more so in Khanal's time, except for a small urbane area in the Kathmandu core.

Behind Khanal's house, that lies right by the ghat in Sankhamul, began the old Newar settlement of Patan with its lines of compact houses and narrow alleys. But in front of his house, on the other side of the Bagmati River, spread stretch after stretch of fields that grew crops and vegetables throughout the year. Depending on the season, rice, wheat and corn and other crops were cultivated, along with vegetables like cauliflowers, potatoes, radishes, garlic, turnips, spinach and the green leafy saag. Farming apart, kitchen gardens were an integral part the concept of houses embodied.

Living in these agrarian settings, the country not yet opened to the outside world, and untouched by technological modernity, food for the denizens of the Valley from Khanal's generation was simple, mostly confined to what their ancestors had passed on to them. The main meals in the morning and evening were comprised of rice, daal and vegetables, in almost all cases produced by individual families in their own fields. Complementing these food was fresh milk and other dairy items like curd, milk, ghee and mohi.

Khanal says that spices that are so extensively part of Kathmandu’s culinary culture today were not in their mothers’ recipes.

“Every vegetable has its own unique taste and smell and texture,” he says. “Mothers in our times used the simple spices of ginger and turmeric that retained these qualities. And the vegetable on the plate smelled the same as it smelled when we plucked it out from the field. The cauliflower smelled like cauliflower, bottle gourd smelled like bottle gourd, and simi [beans] like simi,” he says, adding that the use of too many spices today kills vegetables’ original taste and quality.

Oil used would be mustard oil, pure and locally produced. For Khanal, he got it delivered at his home from no other place than the place best known for it – Khokana.

It is only natural that the concept of breakfast, still largely unknown to Nepal’s food culture today, was missing during these bygone times. Even tea came much later. So, the first thing that touched Khanal's mouth everyday was the morning meal that people ate between 8 to 9 am.

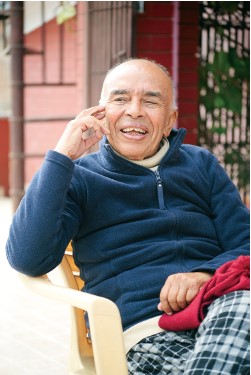

Food was not significantly different for Bhairab Risal, 90, born in Dhadhikot of Bhaktapur. But for his family and many in his village, unlike Khanal's, not every meal was made of rice. Corn and maize were other grains that were used as alternatives to rice as main meals, dhindo, roti, chyankhla (grit) being the different dishes made out of them.

“If some family ate rice daily, most likely it was well to do," Risal says. For his family and others in his village on the outskirts of Kathmandu, rice was prized food that was served on special occasions, or when they had meat.

Like rice, meat was also not easily affordable. The well-off bought it from goat butcheries in Khichapokhari in the core of Kathmandu. But for the majority of Valley denizens, especially those in the villages, meat was a rare indulgence.

“During Dashain or special days like Janai Purnima or Maghe Sankranti, villagers would butcher goats and divide among each other,” says my father.

In spite of this slight difference in food consumption resulting from variations in economic status, the food culture shared by Kathmandu’s common folks in Khanal and Rijal’s younger days or even my father’s time, were very similar. This commonality extended to khaja (afternoon snacks) as well.

“Afternoon snacks meant three things – bhuteko makai bhatmas (roasted corn and soybean), and roti,” my father says. Every day, after returning from school, he and his sisters headed straight to the kitchen where their sister-in-law would have makai bhatmas or roti, along with vegetable— mainly potatoes, radishes or other seasonal vegetables—ready for them.

Ratna Bata Shrestha, 55, reminisces savoring makai bhatmas and roti with fresh garlic, onions or radishes from his farm. “I’d run to our vegetable farm with the makai bhatmas or roti mother gave me and pluck a leaf of garlic or onion or uproot a radish and eat in the field itself,” he says in one breath, in the tone suggestive perhaps of the same childhood excitement he must have carried inside as he ran to the field.

A Newar native of Bode in Bhaktapur, he says that for most Newars, afternoon snack equally meant beaten rice (chiura) or baji as is called in Newari. Shrestha's wife Sabitri agreed, and remembers that often as a young girl she took baji to her parents working in the field.

The labor that went into its preparation made chiura prized, reserved for special occasions like Dashain, and for Newars, their traditional feasts (bhoj). And, the farther back we go, the more prized we find it to be.

“Our mother would have beaten chiura just as Dashain began,” Risal says. “But she’d store it secretly. The whole house smelt of it, but we wouldn’t get anything until when we got meat for the festival.”

Only after the seventh day, when the goat was sacrificed, he got to eat chiura with meat. It would then be served throughout Dashain, after which the family would have to again wait for other special occasions for it.

Even the Newars, Shrestha said, saved the best chiura for bhoj because it was prepared in mortar (okhal) or dhiki (manual wooden thresher), something which was a laborious, tedious process.

Perhaps, it is this labor that went into food production that connected food with the idea of being something hard-earned and to be respected in the imaginations of the generations from yesteryears. One of the common views those I talked to expressed is that food and cooking in those times were woven into a range of intense emotions. They remembered how the process of producing and cooking food involved tremendous dedication and sacrifice by mothers and other females in every family. In the morning, they were the first to rise, well before dawn, so they could fetch drinking water and complete all household chores and cook on time. And in the afternoon, it was them who went to collect firewood for cooking and fodder for the cattle.

Food was cooked in an ageno (traditional earthen stove), and whether it was the mother, sister-in-law or sister cooking, they would have to continuously blow the dhungro (traditional iron pipe to blow fire) to keep the flames going.

“Now that I think of those times, I feel that the females of the houses literally breathed life into the food we ate,” Khanal says.

What was common of the meal times was also how everyone gathering together for meals was a tradition strictly adhered to. “Everyone had to sit down in the kitchen before the plates were filled with food,” my father says.

While food in the Valley was mostly a simple, uncomplex affair, and produced domestically with family members’ own dedication and labor, the idea of food as externally produced, and available in the space outside of home was also gradually emerging around my father’s and Shrestha’s generation. And it was in the urban Kathmandu existing alongside the pastoral where this notion found a boost. It is also important to see that by the mid-1970s, Thamel had already emerged as a hub of hippies, and the place already offered the pizzas, burgers and many other dishes of the West entirely unknown to the Valley’s common populace.

Modernization and increasing interactions with the outer world was also gradually transforming the food of the common people.

Prem Khanal, born in the early 70s in Thapathali, much closer to Kathmandu’s core, is representative of the generation that grew up during this gradual transformation.

“When I was growing up in the 80s, bakery items like loaves of bread and doughnuts were slowly becoming available in the shops,” he says.

As these changed the ways Kathmanduites adapted their snacks and consumed food, Khanal was to witness a revolutionary shift in the food culture of Kathmandu. This concerned momo, a Tibetan delicacy that entered Nepal in the 1960s with Tibetan refugees and Newar traders.

While the first momo shop was already opened in the early 1960s in New Road, the food was still not very popular when Khanal was a young boy in the 1980s.

That the meat was not grilled was something which many people deemed to be “dirty”. And, in those days, momos were only prepared of buff.

“It was something like momo being synonymous with buff,” Khanal says.

Many people raised in different cultural backgrounds that do not accept buff meat found the food unacceptable and disliked it, said Khanal. Hence, only a few eateries limited to places like New Road served momo. And their customers were confined to a small group of people, mainly Newars.

But innovations happened around 1987/88. Some shops started selling momos stuffed with chicken meat instead of buff. It was after this that the dish increasingly became popular among people from different backgrounds. And for Khanal and his friends, what they sought when they had some money was a combined meal of momos and chowmein.

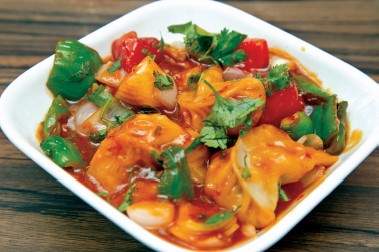

Today, as his son’s generation are growing into teenagers, momo stands as one of the most popular and diversified foods with vegetarian adaptations filled with paneer, cabbage, and tofu instead of meat. And in addition to momos, teenagers and youths today find themselves in the Valley’s sophisticated food culture that blends urban and rural and local and global.

Today, as his son’s generation are growing into teenagers, momo stands as one of the most popular and diversified foods with vegetarian adaptations filled with paneer, cabbage, and tofu instead of meat. And in addition to momos, teenagers and youths today find themselves in the Valley’s sophisticated food culture that blends urban and rural and local and global.

Unlike yesteryears, food is no longer something mostly confined within the realm of the household only. Instead, with the rising culture of street food, it might even be that for this generation of teenagers or youths, food is a matter more of outside than the territory of home.

To teenagers, especially girls like Shrestha’s daughter Sadichhya, 17, the list of staple snacks is ever increasing. The latest addition to the already long list of her generation’s favorite khaja, which includes momos, chowmein, noodles, sausage and a range of other street dishes, is laphing - a Tibetan noodle dish seasoned with spices.

“If I don’t eat laphing for two days or more, I really start craving it,” she says.

But her own Newari meat dishes of choyala, kachela, chatamari and many other food items, staples to her Newari bhoj as much as they are in the restaurants of Kathmandu, have never been erased off that list. The yomari stuffed with chaku or khuwa is among her best sweet dishes.

What her list of khaja explicitly shows is that it is a mixture of both her own Newari traditional food together with a plethora of food from other cultures that came to blend with the cultures of the Valley. And, it is her generation whose tastes and preferences will shape this historical Valley’s food culture in the days to come.

For now, the elderly generation, who saw revolutionary transformation of the Valley’s food culture in their lifetime, receive the commodification of food in Saddhichya’s generation with mixed emotions.

“Food might be more plentiful today than when we were young,” Risal says. “But with so many chemicals used in every crop and vegetable, we are not sure what we are eating.”

He laments the vanishing of the Valley’s fertile soil that grew its healthy crops and vegetables.

That stretch after stretch of land in front of his house now crowded with concrete structures, and Khanal agrees with Risal. He also feels that commodification is attacking the idea of food as an output of labor and something to be respected.

“Until some decades ago, food was hard-earned. It was filled with mother’s love, and we ate with respect,” he says. He feels that today, these are the things that Kathmandu’s food culture is missing most.