Kasthamandap is Nepal’s heritage defined, a witness to its history and evolution as a nation for almost a thousand years— and likely more. No other traditional building in Nepal could compete in size, antiquity or cultural impact. It must not be allowed to perish.

Kasthamandap is Nepal’s heritage defined, a witness to its history and evolution as a nation for almost a thousand years— and likely more. No other traditional building in Nepal could compete in size, antiquity or cultural impact. It must not be allowed to perish.

- Mary S. Slusser

The imposing wooden pavilion called Kasthamandap was the oldest and largest public building in the Kathmandu valley. Known locally as Maru Sattal, it lay at the crossroads of ancient trans-Himalayan trade routes connecting India to Lhasa and Peking. Kathmandu owes its very name to the venerable pavilion. Kasthamandap, therefore, was the physical and symbolic heart of Kathmandu. But Kasthamandap is no more: it collapsed in a pile of rubble after the April 25 earthquake. We must rebuild it to its full glory. Here is why.

The imposing wooden pavilion called Kasthamandap was the oldest and largest public building in the Kathmandu valley. Known locally as Maru Sattal, it lay at the crossroads of ancient trans-Himalayan trade routes connecting India to Lhasa and Peking. Kathmandu owes its very name to the venerable pavilion. Kasthamandap, therefore, was the physical and symbolic heart of Kathmandu. But Kasthamandap is no more: it collapsed in a pile of rubble after the April 25 earthquake. We must rebuild it to its full glory. Here is why.

Kasthamandap served as a rest-house for local residents and weary travelers for almost a thousand years. In later centuries (and perhaps during its hazy early days), it also housed shrines of different deities, including the well-known Gorakshyanath statue established around 1379 AD. In typical Kathmandu style, the pavilion was to serve both functions, secular and religious, for many centuries to come. Also in Kathmandu style, the pavilion was sacred in both Hindu and Buddhist traditions. The legend about Kasthamandap’s origin recounts local residents who, during the annual sattal puja, shouted loudly about the price of oil and salt still not being equal, as a means of ensuring the pavilion’s longevity. Throughout its rich, long history, the pavilion was used for royalty-sponsored, as well as communal, religions ceremonies. Kanphatta jogis, followers of Gorakshyanath, physically lived in the pavilion for centuries until as recently as 1966. In modern times, ordinary citizen, fruit sellers, Hindu and Buddhist devotees and siddha yogis of all stripes have floated in and out of Kasthamandap’s open terraces and floors. In other words, Kasthamandap has always been a lived space, a community center where local residents come together to worship, rest and socialize. And now it is no more.

Kasthamandap served as a rest-house for local residents and weary travelers for almost a thousand years. In later centuries (and perhaps during its hazy early days), it also housed shrines of different deities, including the well-known Gorakshyanath statue established around 1379 AD. In typical Kathmandu style, the pavilion was to serve both functions, secular and religious, for many centuries to come. Also in Kathmandu style, the pavilion was sacred in both Hindu and Buddhist traditions. The legend about Kasthamandap’s origin recounts local residents who, during the annual sattal puja, shouted loudly about the price of oil and salt still not being equal, as a means of ensuring the pavilion’s longevity. Throughout its rich, long history, the pavilion was used for royalty-sponsored, as well as communal, religions ceremonies. Kanphatta jogis, followers of Gorakshyanath, physically lived in the pavilion for centuries until as recently as 1966. In modern times, ordinary citizen, fruit sellers, Hindu and Buddhist devotees and siddha yogis of all stripes have floated in and out of Kasthamandap’s open terraces and floors. In other words, Kasthamandap has always been a lived space, a community center where local residents come together to worship, rest and socialize. And now it is no more.

A city without a mooring to its past becomes a sterile utilitarian cluster of infrastructure and people (the carnal city of Las Vegas alone in the deserts of Western USA comes to mind). If you identify yourself with Kathmandu, and want to be proud of it, you should strive for more: a tie that binds, a sense of belonging, and of being a participant in a rich ancient saga that has unfolded in our precious little valley through the rise and fall of the Kirant, Licchavi and most importantly, the Malla eras. You must long for that intangible whiff of Kathmandu-ness that is very hard to pin down but very easy to recognize if you have encountered it, even if only once. It is in the roadside chhoila, chatamari and aila we love. It is in the subconscious reach of our hands toward temple bells as we walk past. It is in our habit of collecting together in small groups, as the sun wanes low towards Chandragiri, to discuss the day’s affairs and to look at passers-by in the tole squares. It is in the sweetmusty smell of oil incense dust and lightly rotting monsoon damp that wafts past us on our way from Maru towards Indra Chowk. If you long for this, you are intimately and directly connected to the throbbing heart of our metropolis: Kasthamandap. This landmark pavilion represents the physical and symbolic origin of the 600 year long Newar renaissance that has given Kathmandu most, if not all, of its identity. This is why any person who cares about Kathmandu must care about restoring Kasthamandap. In historic, physical and symbolic ways, Kasthamandap is Kathmandu, and vice versa.

A city without a mooring to its past becomes a sterile utilitarian cluster of infrastructure and people (the carnal city of Las Vegas alone in the deserts of Western USA comes to mind). If you identify yourself with Kathmandu, and want to be proud of it, you should strive for more: a tie that binds, a sense of belonging, and of being a participant in a rich ancient saga that has unfolded in our precious little valley through the rise and fall of the Kirant, Licchavi and most importantly, the Malla eras. You must long for that intangible whiff of Kathmandu-ness that is very hard to pin down but very easy to recognize if you have encountered it, even if only once. It is in the roadside chhoila, chatamari and aila we love. It is in the subconscious reach of our hands toward temple bells as we walk past. It is in our habit of collecting together in small groups, as the sun wanes low towards Chandragiri, to discuss the day’s affairs and to look at passers-by in the tole squares. It is in the sweetmusty smell of oil incense dust and lightly rotting monsoon damp that wafts past us on our way from Maru towards Indra Chowk. If you long for this, you are intimately and directly connected to the throbbing heart of our metropolis: Kasthamandap. This landmark pavilion represents the physical and symbolic origin of the 600 year long Newar renaissance that has given Kathmandu most, if not all, of its identity. This is why any person who cares about Kathmandu must care about restoring Kasthamandap. In historic, physical and symbolic ways, Kasthamandap is Kathmandu, and vice versa.

We can be fairly certain that Kasthamandap existed in as far back as 1143 AD (and possibly in 1090 AD). Kasthamandap was founded during the turbulent, sparsely recorded Transitional Period in Kathmandu history that was sandwiched between Licchavi decline and the rise and eventual glory of the Malla rule. The pavilion is by no means the best example of Newar architectural craftsmanship. It lacks tundaals (struts supporting the overhanging roofs) that add deep tantric mystique to temples of the later Malla Era. It also has no carvings and paintings. But what it lacks in stylistic grandeur, Kasthamandap more than makes up in its sheer size, the association of its iconic three tiers with Kathmandu, and the one thousand years of history it captures within its copper-plate inscriptions, statues and rounds of renovations.

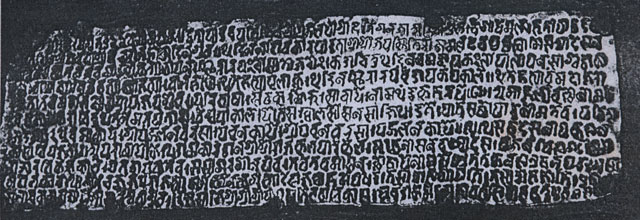

Starting from 1333 AD, no less than six copperplate inscriptions were attached directly to the exterior of Kasthamandap. These inscriptions record various social, cultural, political and religious aspects of then-contemporary Kathmandu. Just to give a flavor, these inscriptions document topics as diverse as the existence of two (or three) townships in medieval Kathmandu, the association of Kasthamandap with Pachali Bhairav, the rise and longevity of the Gorakshyanath cult and its kanphatta disciples, the long (and perhaps longest)-standing Buddhist connections with the pavilion, the gradual merging of local townships into the unified city-state of Kasthamandap-nagar (and subsequently, Kathmandu), the rise of Nepal Bhasa (Newari) as a state language, the dual-kingship sometimes in effect during the Malla era, the continuation of the ancient Licchavi system of coinage/weights, and the importance of guthi associations in the medieval era, still so very relevant in Kathmandu. All of these priceless copperplate inscriptions are now presumed lost or stolen amidst the rubble of Kasthamandap.

Starting from 1333 AD, no less than six copperplate inscriptions were attached directly to the exterior of Kasthamandap. These inscriptions record various social, cultural, political and religious aspects of then-contemporary Kathmandu. Just to give a flavor, these inscriptions document topics as diverse as the existence of two (or three) townships in medieval Kathmandu, the association of Kasthamandap with Pachali Bhairav, the rise and longevity of the Gorakshyanath cult and its kanphatta disciples, the long (and perhaps longest)-standing Buddhist connections with the pavilion, the gradual merging of local townships into the unified city-state of Kasthamandap-nagar (and subsequently, Kathmandu), the rise of Nepal Bhasa (Newari) as a state language, the dual-kingship sometimes in effect during the Malla era, the continuation of the ancient Licchavi system of coinage/weights, and the importance of guthi associations in the medieval era, still so very relevant in Kathmandu. All of these priceless copperplate inscriptions are now presumed lost or stolen amidst the rubble of Kasthamandap.

Very little has been said in the media about the demise of Kasthamandap. Two months after the earthquake, the site was still a pile of rubble, with local residents establishing make-shift tents directly on top of the rubble to escape aftershocks. While our hearts weep for our brothers and sisters traumatized by the earthquakes, we must also ask: do we realize they are sitting atop a pile of history that would be the envy of any civilization? Mary Slusser, the Doyenne of Kathmandu culture and history, believes the four enormous wooden columns and the great central platform, at the very least, date back to the original construction of Kasthamandap. Imagine the value of the wood and bricks, even fragments of them, if they are indeed 900 years old. While the larger wooden remains are now stored within the Hanumandhoka Palace complex (unmarked, and mixed-in with other Darbar Square remains), the precious bricks and other remains are completely unaccounted for. They were eventually bulldozed off in a crass manner by cranes and trucks. Where are these ancient relics now? What have we, citizen and keepers of our priceless living culture, done to seek them out? Where are our public servants, officially responsible for the safeguarding of our heritage sites?

Very little has been said in the media about the demise of Kasthamandap. Two months after the earthquake, the site was still a pile of rubble, with local residents establishing make-shift tents directly on top of the rubble to escape aftershocks. While our hearts weep for our brothers and sisters traumatized by the earthquakes, we must also ask: do we realize they are sitting atop a pile of history that would be the envy of any civilization? Mary Slusser, the Doyenne of Kathmandu culture and history, believes the four enormous wooden columns and the great central platform, at the very least, date back to the original construction of Kasthamandap. Imagine the value of the wood and bricks, even fragments of them, if they are indeed 900 years old. While the larger wooden remains are now stored within the Hanumandhoka Palace complex (unmarked, and mixed-in with other Darbar Square remains), the precious bricks and other remains are completely unaccounted for. They were eventually bulldozed off in a crass manner by cranes and trucks. Where are these ancient relics now? What have we, citizen and keepers of our priceless living culture, done to seek them out? Where are our public servants, officially responsible for the safeguarding of our heritage sites?

When Dharahara collapsed in the major earthquake of 2015, photos immediately circulated in Nepali social media of “priceless” bricks dating back to Juddha Samsher’s time (1934 AD). Should we care more about copper-plate inscriptions, wood splinters and bricks that predate Juddha Samsher by at least 780 years?

When Dharahara collapsed in the major earthquake of 2015, photos immediately circulated in Nepali social media of “priceless” bricks dating back to Juddha Samsher’s time (1934 AD). Should we care more about copper-plate inscriptions, wood splinters and bricks that predate Juddha Samsher by at least 780 years?

The lack of public grieving for Kasthamadap’s demise is partially explained by the popular myth that it was built by Laxmi Narsingh Malla (ruled 1621-1641 AD). This incorrect -- and much later-- dating is inexplicably but consistently repeated in 19th century Kathmandu Vamsavalis (written records of various eras and reigns), and eventually picked up and repeated by early 20th century Western accounts of Nepal. The myth was refuted by the rigorously disciplined Nepali research group Samshodhan Mandal more than 25 years ago. However, the myth has endured. Most of us are therefore not too concerned about Kasthamandap’s fall because it was “only 400 years old”.

We must take immediate steps to secure the remains of Kasthamandap, and to plan its renovation. Private groups are trying to collect funds towards this, but there are no commitments or a formal plan yet. Kathmandu residents with deep connections to this venerable sattal must get involved to make sure that the funds do get collected, that the rebuilding does happen, and that it happens in a faithful, earthquake-resistant manner. Along the way, we must not be shy about demanding accountability and results from our public servants, who are paid with our money to take care of heritage sites like Kasthamandap. An immediate challenge here seems to be confusion about which institution owns the main responsibility for heritage conservation: The Ancient Monuments Act assigns the responsibility to the Department of Archaeology, but local governance laws point to municipal bodies. Then there are NGOs such as Kathmandu Valley Preservation Trust and others. Let us fix this by assigning clear roles and responsibilities, transparent chains of command, and clear coordination between all relevant groups. Modern Information Technology makes the management and communication of all this straightforward. What is more challenging, of course, is for all stakeholders to agree on policy and priorities. But it must be done.

We must take immediate steps to secure the remains of Kasthamandap, and to plan its renovation. Private groups are trying to collect funds towards this, but there are no commitments or a formal plan yet. Kathmandu residents with deep connections to this venerable sattal must get involved to make sure that the funds do get collected, that the rebuilding does happen, and that it happens in a faithful, earthquake-resistant manner. Along the way, we must not be shy about demanding accountability and results from our public servants, who are paid with our money to take care of heritage sites like Kasthamandap. An immediate challenge here seems to be confusion about which institution owns the main responsibility for heritage conservation: The Ancient Monuments Act assigns the responsibility to the Department of Archaeology, but local governance laws point to municipal bodies. Then there are NGOs such as Kathmandu Valley Preservation Trust and others. Let us fix this by assigning clear roles and responsibilities, transparent chains of command, and clear coordination between all relevant groups. Modern Information Technology makes the management and communication of all this straightforward. What is more challenging, of course, is for all stakeholders to agree on policy and priorities. But it must be done.

Certainly, we must restore Kasthamandap for future generations, so that they may revel in its presence, as so many of us have over the last 900 years. We must also do it to rekindle tourism as a contribution towards reviving Nepal’s post-quake economy. But most of all, we must do it for ourselves, the citizen of Kathmandu, some of us descendants of the very builders of Kasthamandap. The Newar culture that peaked in the late middle ages was born in the making of Kasthamandap. The spirit of our metropolis courses through our many bahas, bahis, stupas, pithas and temples, collects in our streets and gallis, but is finally rejuvenated and sent gushing back to us by the throbbing heart of Kasthamandap. Restoring Kasthamandap is the first step towards a physical and spiritual renewal of Kathmandu. Without Kasthamandap, we would be living in a city whose heart has stopped beating.

Certainly, we must restore Kasthamandap for future generations, so that they may revel in its presence, as so many of us have over the last 900 years. We must also do it to rekindle tourism as a contribution towards reviving Nepal’s post-quake economy. But most of all, we must do it for ourselves, the citizen of Kathmandu, some of us descendants of the very builders of Kasthamandap. The Newar culture that peaked in the late middle ages was born in the making of Kasthamandap. The spirit of our metropolis courses through our many bahas, bahis, stupas, pithas and temples, collects in our streets and gallis, but is finally rejuvenated and sent gushing back to us by the throbbing heart of Kasthamandap. Restoring Kasthamandap is the first step towards a physical and spiritual renewal of Kathmandu. Without Kasthamandap, we would be living in a city whose heart has stopped beating.

For more on Kasthamandap, visit www.rebuildkasthamandap.com

Note: Photos from above - Min Ratna Bajracharya (the first three photos), Prajwol Maharjan, Hari Maharjan, Kashinath Tamot(2009 publication in www.nepalmandal.org), Hari Maharjan, Sameer Tuladhar.