“It would be all right if all my works were burned, except for Muna Madan,” the Nepali poet Lakshmiprasad Devkota is reported to have said on his deathbed in 1959. His epic poem - Muna Madan - is a long tragic romance in verse form about a husband who sets off as a trader for Lhasa leaving behind his beloved wife and mother. The poem represents a relatively early and naive work in the career of Nepal’s most famous and prolific twentieth century writer. However, for all its simplicity in narrative and structure, Devkota managed to capture something in the essence of Muna Madan which can arguably never be replicated. As a work of Nepali literature, it stands on the threshold of modernity, borrowing themes from Sanskrit poetry and Newari literature as well as reclaiming the populist jhyaure folksong tradition. At the same time, it forges a new Nepali literary identity based on simple homely values, love and inclusiveness. In this way the poem manages to look both at the past and at the future, remaining fresh and timeless for readers.

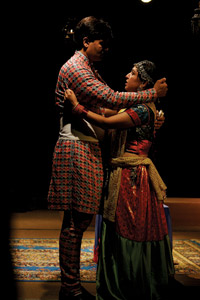

The poem’s principal characters Muna and Madan are a young couple struggling to make ends meet in 1930s Kathmandu. The poem, often though not always in dialogue form, opens with Madan announcing his decision to travel to Lhasa (Tibet) to seek his fortune in order to take proper care of his wife Muna and his aging mother. Muna responds in a flood of tears. She is agonized by the prospect of losing her beloved husband but Madan holds fast in the face of her entreaties; he must go but promises to return within forty days. In his absence Muna pines for Madan. The words of various urban characters make Muna pine all the more as they attempt to sow seeds of doubt in her mind by suggesting that Madan has forgotten her or has died along the way. In fact Madan has arrived in Lhasa and is so enchanted by the city of the gods that he does forget all about his promise to Muna and remains there for several months. One day, however, he abruptly realizes how much time has passed and sets out across the passes with a group of fellow traders in order to return to Kathmandu. On the way Madan contracts cholera and is left for dead in the forest by his heartless companions. There a local man, a Tibetan who lives alone with his children in the forest, saves Madan, takes him in and painstakingly nurses him back to health. When Madan is fully recovered he takes his leave of the Tibetan, offering him a bag of gold for his kindness. The Tibetan rejects the offer on the grounds that he has no need for riches. Madan returns hastily to Kathmandu but he is too late – Muna has died of a broken heart and his mother of old age just before his return. Madan is so grief stricken that he falls ill and ordering the doctor to leave, he too succumbs to his sorrow and dies. That is the sad tale of Muna Madan.

The poem’s principal characters Muna and Madan are a young couple struggling to make ends meet in 1930s Kathmandu. The poem, often though not always in dialogue form, opens with Madan announcing his decision to travel to Lhasa (Tibet) to seek his fortune in order to take proper care of his wife Muna and his aging mother. Muna responds in a flood of tears. She is agonized by the prospect of losing her beloved husband but Madan holds fast in the face of her entreaties; he must go but promises to return within forty days. In his absence Muna pines for Madan. The words of various urban characters make Muna pine all the more as they attempt to sow seeds of doubt in her mind by suggesting that Madan has forgotten her or has died along the way. In fact Madan has arrived in Lhasa and is so enchanted by the city of the gods that he does forget all about his promise to Muna and remains there for several months. One day, however, he abruptly realizes how much time has passed and sets out across the passes with a group of fellow traders in order to return to Kathmandu. On the way Madan contracts cholera and is left for dead in the forest by his heartless companions. There a local man, a Tibetan who lives alone with his children in the forest, saves Madan, takes him in and painstakingly nurses him back to health. When Madan is fully recovered he takes his leave of the Tibetan, offering him a bag of gold for his kindness. The Tibetan rejects the offer on the grounds that he has no need for riches. Madan returns hastily to Kathmandu but he is too late – Muna has died of a broken heart and his mother of old age just before his return. Madan is so grief stricken that he falls ill and ordering the doctor to leave, he too succumbs to his sorrow and dies. That is the sad tale of Muna Madan.

The poem’s central message is that material wealth cannot compare with the value of familial bonds and interpersonal relationships. This idea recurs throughout the poem but is famously captured in the following lines spoken by Muna:

What’s to be gained, Lord, leaving her [Madan’s mother] for Lhasa?

What’s to be gained, Lord, leaving her [Madan’s mother] for Lhasa?

Bags of gold are dirt on your hands, what can be done with wealth?

Better to eat nettles and greens with happiness in your heart,

Oh my beloved, with a wealthy heart!

Madan learns this lesson the hard way, by losing everything of real value to him. His avarice accounts for his undoing though we sympathize with him since it was for his mother and Muna’s benefit as well as his own that he set off for Lhasa in the first place. For all his ignorance about the true values of life, Madan does show a progressive attitude towards his low caste rescuer, the beef-eating Tibetan. Speaking about himself, Madan says:

This son of a Kshetri touches your feet,

But touches them not with contempt,

A man must be judged by the size of his heart,

Not by his name or caste.

These are important lines in the poem since they foreground Devkota’s rejection of the validity of the Hindu caste system which was not officially abolished in Nepal until 1963 and still holds enormous sway over society today. In the poem the Tibetan is the lowliest of all the characters in terms of caste and social station yet he is also seen as the most noble by virtue of his acts of unconditional kindness to a stranger; here the influence of the English Romantic poet William Wordsworth, with his insistence on the spiritual purity of the simple life, can be keenly felt in Devkota’s work.

Though Madan describes himself as a ‘son of a Kshetri’ in the poem, academic commentators largely agree that Devkota probably had in mind a member of a Newar Hindu caste for his poem’s lead character. The reason for this is that the narrative of Muna Madan is based on a tradition within Newari literature which focused on the lives of Kathmandu-Lhasa traders. Historically these men belonged to Newar Buddhist castes such as Uraay and Bania but it seems Devkota deliberately ‘Hindu-fies’ his main protagonists, perhaps in order to make his poem more appealing to a wider Hindu readership. It is clear from the many references to Hindu deities in their dialogue that Muna and Madan are a Hindu couple. Anxiety on the part of the wives of Newari traders about the beauty of Tibetan women in Lhasa is a common theme in the literary tradition that Devkota borrowed from. Historically, many Newari traders did in fact marry Tibetan women and raise families with them in Lhasa. Foreign women, it has been suggested, represent the greatest threat to the Newari trading community by disrupting the solidarity of the homestead. Nowhere is this more clearly symbolized than in the Simhalasarthabahu Avadana in which beautiful foreign women turn into demons and devour a caravan of Newari traders.

Though Madan describes himself as a ‘son of a Kshetri’ in the poem, academic commentators largely agree that Devkota probably had in mind a member of a Newar Hindu caste for his poem’s lead character. The reason for this is that the narrative of Muna Madan is based on a tradition within Newari literature which focused on the lives of Kathmandu-Lhasa traders. Historically these men belonged to Newar Buddhist castes such as Uraay and Bania but it seems Devkota deliberately ‘Hindu-fies’ his main protagonists, perhaps in order to make his poem more appealing to a wider Hindu readership. It is clear from the many references to Hindu deities in their dialogue that Muna and Madan are a Hindu couple. Anxiety on the part of the wives of Newari traders about the beauty of Tibetan women in Lhasa is a common theme in the literary tradition that Devkota borrowed from. Historically, many Newari traders did in fact marry Tibetan women and raise families with them in Lhasa. Foreign women, it has been suggested, represent the greatest threat to the Newari trading community by disrupting the solidarity of the homestead. Nowhere is this more clearly symbolized than in the Simhalasarthabahu Avadana in which beautiful foreign women turn into demons and devour a caravan of Newari traders.

Muna, too, is troubled by this anxiety:

The maidens of Lhasa, [their] nimble eyes, sculpted in gold,

[Their] nightingale speech, roses flowering in [their] cheeks,

Let them all play, let them all dance, on the hills and the pastures

But Devkota’s poem does not contain the misogynistic paranoia that some of its source materials could be argued to contain and in this way too it confirms its modernity. Madan is unmistakably the poem’s weakest character. Although Muna does a lot of weeping in the poem, when she visits the gossip-loving barber’s wife to have a pedicure, she reacts as follows to the insinuation that Madan has forgotten about her in Lhasa:

From her eyes shone a momentary fork of lightening, gone in a flash.

Patiently, with tenderness, she said, ‘Oh my friend the barber’s wife!

You must understand that I do not think like others, my friend:

If this type of talk reaches strangers’ ears they shall listen eagerly.

In her heart Muna does not doubt the constancy of her husband and this behaviour befits the dedication that is expected from a separated lover in Sanskrit epic poetry which explores the concept of viraha (the pain of longing), another tradition that Devkota drew on in his composition of Muna Madan. By the end of the poem we learn that Muna’s earlier pleadings were imbued with a prophetic power wholly lacking in Madan’s own plans:

But if you forget me, these tears will cause you suffering: this I say in fear.

Be on your way, bringing darkness on the house and the town.

Madan is seen as inferior to his mother in terms of understanding as she recognizes, in her dying words, the truth that is the kernel of the poem’s message:

What I have given I take with me, what goes with me in truth?

The wealth you acquire in this dream is in your hands when you wake.

But it is the humble Tibetan who teaches Madan the error of his ways. The Tibetan’s wife has died (“the clouds are her only jewels”) and his subsequent suffering has afforded him insight:

What’s the use of gold, of wealth, when Fate has plucked her away?

He has become wise through suffering, and through wisdom, the kind father of two happy children. This is the process that Madan must also now undergo but tragically he has left it too late; his wife is dead, he is childless and his mother is about to die too. Although it is too late for Madan, it’s not too late for us, the readers, to learn and we are addressed directly by the poet in the final lines of the poem in an echo of poetry from the Bhakti tradition:

Have you washed the dust from your eyes, brother and sister?

If life were just eating and drinking, Lord, what would living be?

Our deeds are our worship of God, so says Lakshmiprasad.

The particulars of Muna Madan may feel dated to a modern reader, after all border crossings have closed and rapid change has affected almost every aspect of Nepali society in the last half century, but the poem’s main concerns remain as topical today as ever. With the continued migration of rural people to urban centres and the huge number of young married Nepali men seeking financial security by working abroad, the decisions Madan is forced to make and their possible ramifications will chime with the lives of many ordinary Nepali people today and for many years to come. Also, anyone at all familiar with village life will recognize as distinctly Nepali the simple homespun wisdom which the poem peddles. And if anybody doubts whether Muna Madan really is a poem read and enjoyed by ordinary people today I would respond by saying that it is the only poem in any language I have ever heard teenage schoolgirls happily recite from at length, in this case on the roof of a bus on a winding mountain road in Dolakha.