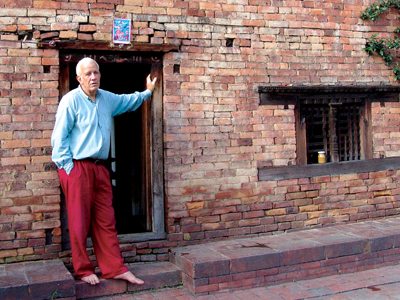

We left Bhaktapur and headed for Jaukhel, crossed a bridge, turned left and after some looking around, found the narrow path that led towards the woods. Walking for about five minutes on this mud path, we found a still narrower path on the right that went through lush green paddy fields. We walked the final bit up some wet steps of large bricks and stone, and there above us stood Niels Gutschow, standing barefoot; smiling, as if relieved that we had not lost our way. The house stood on top of a tree-lined hill, looking every bit like a typical Newar dwelling, except for the pati, which has a washbasin at one end, a table and some chairs that distinguish it from its counterparts around Bhaktapur.

From the moment we met, Niels seemed like an extraordinary man. Totally dedicated to research and writing books, he tells us, “If I stack up my books, they will stand one meter tall, but of course, many of them are in German.” That, however does not mean he has no time for other interests. He has added a few constructions around the old house. “I have to practice, no? And I like to experiment with different materials and different designs,” he goes on to

From the moment we met, Niels seemed like an extraordinary man. Totally dedicated to research and writing books, he tells us, “If I stack up my books, they will stand one meter tall, but of course, many of them are in German.” That, however does not mean he has no time for other interests. He has added a few constructions around the old house. “I have to practice, no? And I like to experiment with different materials and different designs,” he goes on to

explain as he shows us around the compound. Amazingly, Niels has refrained from using cement and all the walls are plastered with clay, although we would have failed to notice on our own. A man passionately involved in restoration and conservation, he loves to leave things as he found them. The windowsills in his house are worn out with age, and the wood of the latticed windows is broken in places. The wooden steps - seven are mandatory (six are meant to deceive demons) - leading up are typical Newar, left unchanged. The wooden ground floor is one major change from the original construction and the top floor with beautiful natural lighting and slanting wooden ceiling, are the only western influences in the design. The top floor serves as his work place where we found Bijay Basukala (with whom he worked for 17 years) making some fine drawings of Tibetan chörtens.

Niels is not just a writer; he is an architect first. We could sense his love and passion for his work in every gesture and explanation that he gave for all that he has created around the house. A guest- house he built with brick, mud and wood behind the old house, can accommodate quite a few visitors with sleeping arrangement on the floor. The walls are lined with books. We came upon some wooden pillars, which he had brought all the way from South India and has already shipped some to Germany. The chaitya in the shape of a Kadam Chörten he has added to the landscape is only appropriate as he published his massive work, “The Nepalese Caitya” in 1997. It is the most extensive research on chaityas of the Kathmandu valley. He has written several books on Bhaktapur and one of them is entitled “Bhaktapur.” Another book, “Newar Towns & Buildings,” was written in collaboration with Indologist, Bernard Koelver and linguist, Ishwaranand Shresthacarya. At the moment, Gutschow is working on a book on ‘Nepalese Architecture’ and has only recently returned from a trip to Tibet. There he researched the Jhokhang Monastery in Lhasa, which according to him (besides fragments of chaityas) is the only extant building, representing Lichavi period architecture, built by Newar craftsmen 1350 years ago. A massive book on Benaras (Banaras) is to be published very soon. His work rate is staggering, as when he is away, he regularly produces books in his mother tongue, German, concentrating on 20th century urban planning in middle Europe.

Recently, the Itumbaha of Kathmandu made much news headlines after restoration saved it from certain ruin. This was one of the many restoration works undertaken by Gutschow around Kathmandu valley. Another famous undertaking of his was, in collaboration with Goetz Hagmueller and supported by 25 dedicated carpenters from Bhaktapur, the Chyasalin Mandap in Bhaktapur Durbar Square - a present to the Nepali people, presented by chancellor Helmut Kohl in 1987. It was rebuilt from scratch in accordance to historical photographs, which ironically, were well preserved while the pavilion itself had been totally destroyed by the great earthquake of 1934. Making use of some original pillars and lintels and mostly new woodwork, the pavilion was built from the ground up. This new pavilion has been featured in many a magazine.

Niels made his first trip to Nepal in July 1962, while on his way to Burma and Japan. He crossed the Caspian Sea by boat, changed buses a hundred times and crossed Afghanistan through Mazar I Sharif. After spending some time in a monastery in Burma, the French colonial Messageries Maritime took him from Singapore to Kobe. In Japan, he worked as a carpenter. He also crossed the Pacific and Atlantic oceans by boat, exploring the United States of America with his brother who lives in Vermont. He spent only a couple of weeks in Nepal then, but the Himalayan country had already charmed him as he reminisces, “I already knew I would be coming back.” Before arriving in Kathmandu, he had met a Rana gentleman in Jaipur, who gave him a letter addressed to his father in the capital. The elder Rana accepted the letter and lent his German guest a cottage behind his Lakshmi Niwas palace in Maharajganj. It was a grand introduction to life in Nepal and he remembers attending the Rato Matsyendranath festival in Patan.

Born on 27th November 1941, in Hamburg, Niels Gutschow came into a world torn apart by the Second Great War. He received most of his education in Hamburg, but after high school decided to see the world rather than start with his studies. Surprisingly, his father consented, and he set out on his long voyages. After traveling around the world, he decided to study architecture, which he completed in 1970 from Darmstadt, Germany. He then returned to Japan for his PhD. on Japanese cities. At the age of twenty-three, he got married, but he likes to explain, “We in the west get married twice. The first is a learning experience, something like an initiation, and then comes the real thing.” So his first marriage ended in divorce and then in 1989, he walked into a government office in Dilli Bazaar and tied the knot (or rather put his thumb prints on paper) with Wau, with whom he lives in Tahaja, Bhaktapur. Wau hails from Ludwigshafen. The two met in Germany and now share three daughters and a son. They have been blessed with seven grandchildren whom they love to visit and are eagerly awaiting a visit by two of them, who will arrive in Bhaktapur next April.

Back in 1970, Niels paid his second visit to Nepal; this time to study the gates of Marpha and Tukche. It was then that he heard of the German embassy’s plans to set aside funds for the restoration of the dilapidated Pujari Math (Hindu priest’s dwelling place in the past centuries) in Bhaktapur. After seeing the ruins, he made a proposal for its restoration. “It’s a most wonderful building, but it was in ruins and on the verge of collapsing,” says Niels, recalling the state of the Pujari Math before it was restored. He and a few friends were assigned the job by the German Foreign Ministry, and they started work in 1971, receiving just a small allowance. “We worked for pleasure; we really enjoyed doing the work,” explains Niels. “The first secretary of the German Embassy, Heinrich Seemann, came up with an ingenious idea,” recalls Gutschow, “And decided to restore the building as a wedding gift to King Birendra.” It was a very unusual present and is now the ‘Woodcarving Museum,’ harboring some of the finest works in wood around the valley.

Niels was at the time in and out of the country quite frequently. He went back to Germany and returned in 1974 with a scholarship to work in Bhaktapur on ‘Urban Space & Rituals.’ He also prepared the seed paper for the Bhaktapur Development Project which was funded by the German government for a period of twelve years. The project got underway in 1974 and Gutschow got busy working on his research on urban space and rituals, documenting processional routes and mapping the social topography. It was then that he made a big decision in life: “I will work for the rest of my life in Bhaktapur,” he told himself.

He has also kept himself busy writing books in German on Urban Planning History, besides working on archives in Russia and Poland. He often visits his twin brother who lives in Japan and says, “There is a group of Japanese and German experts in conservation, who meet to discuss ideas and the philosophy of conservation; we architects like to exchange ideas and learn from each other, but this does not happen in Nepal.” That aspect of sharing ideas seems to be non-existent in Nepal. Niels has experienced hindrance rather than sharing of ideas while working on projects in Nepal. He exclaims, “Working on the Itumbaha restoration was one of the most difficult projects, because we received little co-operation from the parties involved, but ran into trouble instead. Thus, I have decided not to undertake such projects again.”

In 1980, Niels came back to Nepal along with ethnomusicologist, Dr. Gert Wegner, who came to study the drums of Bhaktapur. Wegner went on to establish and run the Department of Music of the Kathmandu University in Bhaktapur. Gutschow had come to carry out an architectural survey of Gorkha and Nuwakot under the funding of the German Research Council, documenting the palaces of the early centres of Nepal. When this project was over, he began work on the book on Chaityas, which took ten long years of research. At the same time he wrote a host of books in German. Talking about the book on chaityas, he says, “There are about three thousand chaityas in and around Kathmandu valley, so I chose three hundred of the historically most interesting ones among them to document - but I have seen them all!”

The German Research Council sponsored projects in northern Nepal in the early nineties. Niels headed to Mustang to document ritual actions in space in three villages, namely Kag, Khyinga and Te. The latter being “one of the most unique settlements in the world,” as he says. “Documentation is probably the only form of lasting conservation of architectural heritage, as rapid social and economic changes will cause the abandonment of the original settlements in favor of new ones, or rather a house in the Kathmandu Valley,” states Niels.

In 1989, Niels worked on the Swayambhunath Conservation Master Plan. Then in 1992, he joined the German Technical Cooperation, GTZ, the only time he worked with the German INGO. At that time he was involved in the Patan Conservation & Development Programme (1992-93). Along with Hagmueller and Erick Theophile, he worked on the survey, restoration and rehabilitation of quite a few buildings and tried to formulate a policy for architectural preservation. He even proposed scrapping the Ancient Monuments Act entirely in order to get rid of an outdated British legacy and replace the law along the lines of modern conservation policies adopted globally since the 1960s. But HMG decided to add another amendment to turn the law into an impenetrable jungle.

Asked why so many Germans love Bhaktapur, Niels replies, “Many young German architects come here. It’s like the realization of a dream. A similar experience is not found anywhere else in the world.” He adds, “In their circle, architects always discuss urban space and have a sentimental attitude towards this subject. However, the discourse in the West about the sense of ‘place’ and the meaning of ‘urbanity’ is constantly fuelled by such an experience. One could call it ‘learning from Bhaktapur’ - not from Las Vegas, as a critic said in the 1970s. ‘Learning’ is not meant literally, but it implies a growing sensitivity towards the complexities of an urban scene beyond pure consumerism. Bhaktapur is unique and over the years, I have begun to understand and appreciate the different roles played by each individual in the Bhaktapur society.” He is fascinated by the complexity of life here and loves to observe the slow and at times sudden changes taking place.

The peaceful setting of his home in Tahaja is the ideal work place for Niels, and these days, he rarely ventures out. “We don’t need to go out,” he says. “And happiness is working on books like the one on caityas. To look at detail for years, to slowly learn by touching these details, an architectural historian enjoys an experience akin to enlightenment. It is a kind of meditation, not much different from what the Buddha achieved under the Bodhi tree.”

As we walk down the steps together, Wau informs us with a twinkle in her eye, “In the evenings, the owls start to hoot and soon the jackals begin to howl.” Obviously, the couple loves the natural surroundings they live in, and are happy to be away from the motor road and the bustle of the city. The trees they have planted around their vast compound have grown big, and there are no boundary walls to separate them from the neighbors. As we head back, Niels leads the way, and is soon far ahead of us, walking briskly along the narrow path, with no trace of aging in his gait. At 63, Niels Gutschow seems to be enjoying the fruits of having lived close to nature, devoted to research and conservation with unrestrained passion.

Some lesser-known vegetable dishes from the southern plains

I’m not a vegetarian but I love vegetables. And whenever I get to the southern plains of Nepal, I try...