A lot more needs to be done to make Nepal’s beautiful handicrafts more competitive in today’s globalized world.

Be it via grassroots brands, personal connections, or what have you, the element of ‘special items’ has a peculiar place in developing nations such as Nepal, that demands recognition. Niche production avenues that can represent a sense of identity, storytelling, and cultural presence have started growing at high rates due to the nature of the global industry and market forces.When one immediately thinks of Nepal’s export handicrafts, you’d generally think of pashmina shawls, khukuri knives, sarangis, thangkas, clothes, and so on.

It is no secret that in the 21st century, traditional artisan narratives seem to be predominantly ‘up against it’ throughout the Third World, mostly due to being undermined by cheaper, lower quality artificials, such as plastic and cement products, taking their place, but also due to a lack in consumer demand and the base cash flow being diminished by globalization and corporate businesses.

The concept of an ‘up against it’ artisan due to globalization may be coming full circle. A contemporary revolution of appreciating a defrosted window of tailored items that are qualified iconographic; handmade, unique, thought provoking, and/or protruding a sense of spirituality or ‘exoticness’. Throughout the saturated market of products for tourists, collectors, circumstantial locals, and the like, there is often a lack of this ‘unique item’ catching your peripherals if you’re dancing in the rivers of the streets of Thamel and Jham’el this July. It’ll more likely be online.

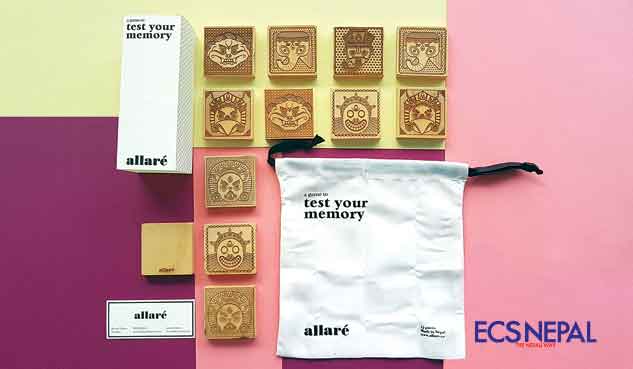

ECS Nepal sent me to inspect a company that is producing such items, Allare, a small startup that has been steadily releasing small batches designed by them and outsourced to artisans, and packaged and sold. In Kazi Studios, a modern-oriented open office space, I met with the brain of the project, Kreeti Shakya.“My brand’s goal is to make things that are Iconic,” she says, opening a white box, with minimalist black latticed design, to show a USB 3.0 pen drive “Many people see this and they know it’s from Allare; it’s iconic.” The drive has a wooden casing with the intricate carving of the face of a wolf, in a design drawn with inspiration from styles evident in Nepal’s sacred spaces.

She shows us a series of her works that are on the market today, most of which have a theme within them telling a story, and paying homage to cultural roots, besides being recognizable—from an aluminum bookmark inspired by the latticed woodwork of Newari windows, to an anodized bottle opener, to coasters that are laser cut, and Nepali traditional pottery and metal utensils used in everyday life for centuries, but lacking presence in modern urban Nepali homes.

“I think I owe it as a mother to be able to keep the stories of these artifacts alive, not only for my child, but for all of those worldwide, Nepali or non-Nepali,” she says. This responsibility of educating people on Nepali culture and identity through new products in simple design that neatly pleases—essentially, this is a case in point of iconography and postmodernism.

Starting seven years ago as a one-off venture, and fresh from her design studies in the U.S., the project is still part time, and full of prototypes. “We usually make around twenty of each item, put them on the market, and see the response. It’s quite a large effort even producing twenty pieces, as they are all handmade,” she explains, adding, “I hire local artisans and pay them a wage for their work that is fair. If they are doing quality work that can sell, and present the idea to us, then they deserve to be given a decent salary.” Indeed, with statistics pointing to more of these skilled laborers shifting their careers abroad for a salary that can support a family, a rise in employing and using artisans to export niche products could be one of many solutions towards creating a Nepali Industry that has full local ownership, pride, and expertise.

As mentioned, there is a saturated market competing to sell such items that are gift-able and iconographic. The industry can be cruel. “I keep many of my design methods and practices out of the public eye while they are made, as I don’t want people to steal ideas and undermine the concept,” responds Shakya to my question of exactly how the items are made.

The market has an increasing number of platforms to release their work, as well, with the #made in nepal campaign starting to gain traction; it is not alone, though. This campaign is marred by no one securing the brand export rights, and a search in Facebook will provide you with over ten pages claiming stake to the brand and logo of ‘Made in Nepal’. Though it is commonly practiced to describe that the product was ‘Made in Nepal’, it hasn’t been commercialized, as other countries have.

Research on the Made In Country index 2017, published by German company Statista, shows that branding a nation and its outbound products with such a title increases knowledge of the country, and also a sense of quality assurance and international perception/association. The research conducted with 43,034 respondents from 52 countries, describing the perception or image of the country and its relevant growth or demise through variables of gross sale, exporting presence, and product quality/satisfaction.

There needs to be quality that is visible,which creates respect that doesn’t just sell one Nepali brand, but generates trust in all. Nepal has a great capacity to win hearts, be it through its beautiful people, its diverse flora and fauna and lovely landscapes, its many religions, or its famous handicrafts. Expanding discussions and representations of the broad identity and artworks of Nepal, besides improving their quality, is a way to preserve and celebrate culture and tradition. It keeps our artisans inspired and busy, and brings home the rice