123 years ago this month, on December 1, 1896, Buddha’s birthplace was ‘discovered’ in the Nepal Tarai. If you’ve read much about Lumbini, you may know that two people claimed to have discovered it, after it had been lost for over a thousand years in the fog of history.

Based on his interpretation of the events of that December 1st, a German archaeologist in the employ of British India’s Northwest Provinces claimed to have discovered it. Dr. Anton Alois Führer was a narcissist who inflated his role in finding Lumbini out of all proportion to the truth. The sense of his own importance and a deep-seated need for public attention and professional acclaim drove him to brag a lie.

The other claimant was a historical figure of some notoriety in Nepal who is recognized today as the true discoverer of Lumbini. Gen. Khadga Shamsher J.B. Rana was a man of considerable pride and ambition. Some called him a Prince, and to others he was the ‘Raja of Palpa.’ In fact, he was the Governor of Palpa and adjacent districts in western Nepal, including Rupandehi District where Lumbini is located. As Governor, he represented the Rana government of Nepal, and on this December day he was Dr. Führer’s mentor and host.

The complex and sometimes startling story of that day is told in ‘The Buddha and Dr. Führer: An Archaeological Scandal,’ a book by the popular historian Charles Allen. In it, and from related sources, the true nature of Dr. Führer’s character around whom professional scandals seemed to swirl is revealed,.

Two pillars

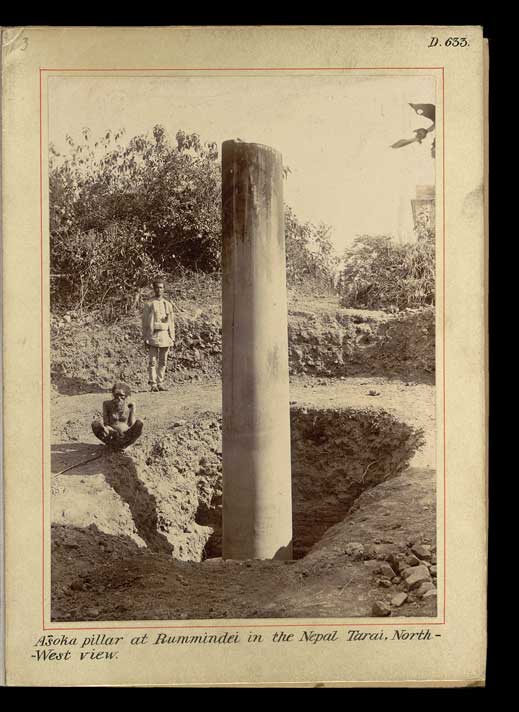

In 1895, while employed by the Archaeological Survey of India in Lucknow, Führer was invited to Nepal by the Ranas to examine a strange object in the Tarai jungle that the indigenous Tharus called ‘Bhimasena-ke-nigali’ (Bhimsen’s Smoking Pipe).

After it was dug out of the earth where it lay partly buried, Führer identified it as a tall sandstone pillar in two pieces, lying near the small Nigali Sagar (pond). Near the top, he found some graffiti scribbles in Nepali and Tibetan but far more importantly, near the bottom he uncovered an edict in ancient Pali dating to the time of King Asoka of India’s Mauryan Empire.

Asoka reigned during the 3rd century BCE. During his rule he traveled widely across India leaving behind numerous edicts inscribed on pillars and rock faces, some of which attested to his visits to sacred sites associated with the life of the Buddha three centuries earlier.

After Khadga read Führer’s report on the Nigali pillar, he went there to see it and confirm the findings. The fact that it was of Asokan origins fascinated his inquisitive mind.

Thus, when a second pillar was found standing erect but mostly buried in a mound near a village called Padariya, 13 miles east of Nigali Sagar, Khadga assumed it was of some importance. To confirm his hunch, in late November 1896, when Führer returned to Nigali Sagar for further research, Khadga sent a message urging him to come to Padariya forthwith. He did, and now the story of who ‘discovered’ Lumbini begins to warm up.

What Dr. Führer saw

Khadga was encamped at Padariya that winter for his annual tour of the Tarai. Expecting Führer to show up on time, Khadga was waiting to show him the pillar. Also present with Gen. Khadga was Duncan Ricketts, in no official capacity other than that he was a manager of a colonial estate no more than five miles south, across the India border. Ricketts and other colonials, scholars, and civil servants were keenly interested in any archaeological findings in the vicinity, and the rumor of a second pillar encouraged him to cross the border to join Gen. Khadga at the site that day.

After Dr Führer arrived and his crew set up his camp at Padariya, he joined Khadga and Ricketts at the pillar mound less than a mile to the north. Führer expressed some confidence that the stone column he was shown there was of Asokan origins. He didn’t need to tell Gen. Khadga to order his sappers to dig the soil away down to the base, for that was already Khadga’s plan; he was waiting for Führer to arrive and see it done.

A short distance from the pillar, Führer also noted a pond south of both the pillar and a small Hindu shrine to the goddess Rummini (Rupa Devi). The shrine, pond, and pillar had all been described in Chinese Buddhist pilgrim journals dating to the early 1st century CE. Though the shrine’s attendant did not allow Führer to enter, he glimpsed in the dark interior what appeared to be a crude sculpture of Mayadevi, the mother of Buddha, at the moment of the Sakyamuni Buddha’s birth.

After Khadga ordered his sappers to dig down to the base of the pillar, Führer inexplicably left the site; perhaps exhausted from the morning’s elephant ride and in need of a meal and some rest.

When he returned late in the day to examine the pillar, Khadga showed him an inscription that had been uncovered near the base. Khadga also gave Führer rubbings he had made of the script. Führer could undoubtedly read enough of it to know it what it revealed about the site, but he seems to have shared remarkably little about it with Khadga.

What Dr. Führer wrote

Three weeks later, after conducting further research near Nigali Sagar, Führer returned to Lucknow and sent the pillar rubbings off to his mentor, Prof. Johann Georg Bühler, in Austria, for detailed interpretation. Shortly thereafter, the eminent Prof. Bühler published the translation to the excitement of scholars around the world, for it clearly stated not once, but twice, that the Lord (of the world), the Sakyamuni Buddha, was born at this place known as ‘lummini-gama,’ the village of Lumbini.

In Lucknow, Führer also wrote up his version of the discovery and sent it to the ‘Pioneer,’ a popular English colonial newspaper in nearby Allahabad, to publish. In it he made the startling claim that he alone had discovered Buddha’s birthplace. A week later, on December 28, 1896, his account was republished in The Times of London for the English-speaking world to read. As you can imagine, the ambitious, acclaim-seeking Dr. Führer was thrilled!

In India, however, his actions set off a firestorm of controversy. Scholars and colonial officials couldn’t believe what they were reading, for nowhere had Fuhrer mentioned or credited his host, nor the presence of Duncan Ricketts as witness to events.

Führer’s official report of the ground-breaking ‘find’ furthered his self-serving version of the discovery. Soon enough, however, a rival scholar who was briefed on what had transpired at Lumbini challenged Führer’s veracity in an open letter to a Calcutta newspaper, later reprinted in a scholarly journal. “It is somewhat amusing,” he wrote, “after all [that] Dr. Führer has claimed in regard to this discovery, to find that not only did he not initiate that search but he had nothing to do with the local discovery on the spot, not even with the unearthing of the famous edict-pillar there, which fixed the spot beyond all doubt.”

These insinuations prompted Führer to ask Gen. Khadga to confirm his (Führer’s) role in discovering Lumbini. Given what Khadga wrote in reply, Führer probably regretted asking.

In his reply, Khadga described the saga, starting with instructions from the Prime Minister about Führer’s initial excavation of the pillar at Nigali Sagar. Khadga then went on to say that when he saw the Rummini-Lummini-Lumbini pillar near Padariya for the first time it “struck me very much for its unique shape and surroundings characteristic of Asoka-pillars.” Gen. Khadga was only too happy, he wrote, “to embrace this auspicious occasion by purposely arranging our meeting... so that I might not lose the opportunity of getting my own views regarding this monolith corroborated by a learned antiquary like you.”

In conclusion, Khadga magnanimously acknowledged that Führer “certainly had a good share in identifying the birthplace of Buddha.” But a “good share” is not the full share nor the main share and in the end what Führer “corroborated” did nothing more than confirm Gen. Khadga’s well-founded hunch and his own principal role in the discovery.

There is much more to the story of Asokan pillars in Nepal in Charles Allen’s book, The Buddha and Dr. Führer (London, 2008). It includes details of Führer’s other scandalous behavior – faking artifacts, plagiarizing the work of other scholars, and the like. Another important source for this story is Führer’s and General Khadga’s ‘Correspondence of 1898: Two letters on the discovery of Lumbini pillar,’ reprinted in Antiquities of Buddha Sakyamuni’s Birth-Place in the Nepalese Tarai, edited by Harihar Raj Joshi and Indu Joshi (Kathmandu, 1996).