After graduating in 1945 with a degree in Fine Arts from Calcutta, the young man who was destined to become Nepal’s best-known artist of the 20th century turned away from painting for a few years to author three remarkable novels. They earned Lain Singh Bangdel equal fame as a popular Nepali writer. Today, more Nepalese may know Bangdel for his novels than for his paintings. As ‘art’, the word and the image are closely related. Before mid-century, Nepalese literature was dominated by romantic novels and sentimental poetry written by and for the upper classes. Then Bangdel, a commoner, made a clean break from the past and wrote three novels of social realism. Two of them describe the lives of Nepalese prabasi (exiles, migrants) who sought employment and settled in northeast India as laborers or soldiers returning from military service after World War-II. The third exposes the suffering of a crippled beggar on the streets of Darjeeling. Each reflects the artist’s Nepalese identity, each displays a level of humanism and authenticity unparalleled in previous Nepali writing, and each is clearly the work of an artist.

Bangdel’s novels portray life ‘as it is,’ featuring the struggles of ordinary people coping with difficult circumstances. He wrote as a naturalist who saw the world as a painter sees it, inscribing its colors and its moods in print. One reviewer said his writing demonstrated “a skill which is attributed to his artistic prowess.” Another noted that Bangdel “used nature excessively,” as if struggling to express visual images that, alas, can only be drawn in words. It was also said that his writing depicts “nature in sympathy with human beings.”

The first novel, Outside the Country, is set in a mountain community near Darjeeling in the mid-20th century. It is a compassionate tale about the dukha-kashta, ‘poverty-induced pain’, of five Nepalese exiles whose ancestral home, like Bangdel’s, was in the hills of eastern Nepal.

A ‘Turning Point’ in Nepali Literature

1947 - Muluk Bahira (Outside the Country)

1949 - Maitighar (Maternal Home)

1951 - Langadako Sathi (The Cripple’s Friend)

Realism in painting and writing presents everyday life in a naturalistic manner. It portrays contemporary people and subjects plainly and truthfully, avoiding the artificial, overly dramatic, and sometimes exotic elements of romantic fiction.

While physically settled within a dominant ‘other culture’, the émigrés of this and his second novel, created a Nepalese subculture far from the ‘home’ to which few would ever return. They suffered a condition that one literary scholar calls “Being Nepali without Nepal.”

In the book’s Introduction, Bangdel is characterized as “a descriptor of nature” as it reflects and influences human behavior and feelings. For example −

…the early sunrise made a lovely scene. The sun’s rays on the mountain peaks gave them a golden hue… Mahila Bhujel was about to go out dressed in his daura-surwal made of fine Tuskar silk. He wears a muffler around his neck, giving him a smart and lively appearance.

When the sun is out Mahila Bhujel is happy, but “Oh!” he laments, “Life is like a shadow, sometimes here, sometimes there… The fond memories of childhood make one cry.”

Similar themes emerge in the second novel, Maternal Home, also written in a naturalistic style. One reviewer tells us that although he never went to Rajbari village, Bangdel –

easily takes me there―and there I see a village under the white spot of a full moon. This is where the soft rays of the sun touch the tall, tall trees on a fall morning. I hear the sound of vegetables frying in Hari’s kitchen and I feel enchantment and sometimes disenchantment over the sound of cicadas.

It isn’t much of a stretch here to smell the herbs and spices, the hot ghee, and the wood smoke from the chulo on which the vegetables are simmering.

The same reviewer also imagines seeing “the fog lifting up in thick plumes” outside his window. “In the life of this story,” he concludes, “there is indescribable sorrow and hidden hopes. In the same way, the whole novel is filled with the monsoon rain and the fall moon of August-September.”

In The Cripple’s Friend, the third and most popular of his novels, Bangdel successfully evokes our humanity (human nature) by arousing the reader’s emotions in the face of profound tragedy. By doing so he approximates Leo Tolstoy's classic definition of art as “a means of communication between people, uniting them in the same feelings.”

The Cripple’s Friend is a poignant saga reflecting mid-20th-century society viewed from street level through the eyes and imaginings of a disfigured beggar. It opens in Darjeeling on a cold winter morning as the golden rays of the early sun touch the sacred Mahakal Baba shrine on top of the hill. Farther down where the sun has not yet reached, we see the frozen trees “shiver with cold” and in protected corners, others look forlorn under “an empire of morning dew.” The narrator then takes us to a wretched roadside hut where, in the dim first light of morning, we see a stray dog sleeping beside the tragic figure of the cripple.

In this short novel, we feel the author’s concern for the poor and downtrodden. In the words of the beggar, he writes that “sympathy for the poor emerges from the hearts of the poor. One beggar knows the pain of another.” The dog, he says, is “a creature similar to me, who begs to eat.”

The beggar’s affection for the dog along with his dreams and nightmares are integral parts of the portrait. Together, they set the stage for a surrealistic, almost Shakespearian, conclusion. Reader beware! After the beggar is ill-treated by an irate person and dies of exposure during a wild rainstorm, the dog searches for him in the town graveyard on the hillside below the high school. A watchman later finds them there, man and dog half buried in the mud and sand, their skeletons entwined.

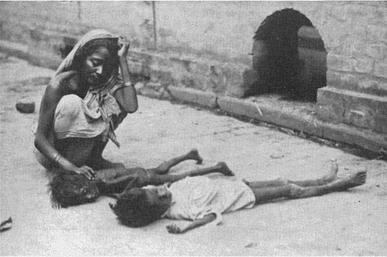

One reviewer has compared The Cripple’s Friend to a painting Bangdel completed in the 1950s entitled ‘Famine in Bengal’. The painting’s evocative quality comes from the elongated physical features (fingers, face, feet) and the artist’s choice of somber blue-green hues that convey despair on the face of the distraught mother holding the lifeless child in her arms next to an empty dish.

Scenes that so vividly portray the human predicament not only reflect what was in the artist’s imagination, they also stimulate ours. Dina Bangdel sees that her father’s strength as an artist “lies in the expressive power, in the depiction of the pathos of his subject matter – of poverty-stricken families, blind beggars, the destitute, the old and the infirm.”

One reader found The Cripple’s Friend to be “a very artistic description of human existence,” a sentiment equally appropriate for ‘Famine in Bengal.’

Each of Bangdel’s novels displays both visual and visceral emotion ― joy, love, happiness, jealousy, fear, misery, great trauma, death, and grief. The novelist moves the reader along from one emotion to the other, something the painter has difficulty achieving on canvas. In the Preface to The Cripple’s Friend, Bangdel says outright, “It is a ‘sketch’ of one beggar and his friend. I thought that writing it on paper would be better than drawing it on canvas.”

Realism in Images and Words

Art speaks with unique voices... An image creates words, but words also create images... ~Lori Greenstone, contemporary artist and author

As a child, Bangdel heard stories about the home his grandparents left behind in Nepal and of their struggles adapting to a new life in the hills of northeast India. He grew up the close-knit, ethnic subculture of a Nepalese laborers’ village on a Darjeeling tea plantation. Some of the principal inspirations for the realism he achieved in his paintings and novels were drawn from those experiences, especially of migrant families far from their ancestral home and of the economic and social traumas and misfortunes they suffered. These are what grounded Bangdel’s identity as a Nepali.

In high school, young Lain’s talents for painting and for writing were recognized and encouraged. He perfected while by studying art and writing novels in Calcutta (1939-50) and by scrutinizing and emulating the styles of the Great Masters. The realism he encountered in Western literature and film also influenced him.

As Dina Bangdel notes, her father’s background and experiences were far different from those of most of his Indian contemporaries. In Calcutta, his creativity benefited from his identity as a Nepali born and raised in the Himalayan hills, and it is clear that the autobiographical overtones from his youth and young adulthood show up in his early paintings and his novels. Later in life, the strong Nepalese themes he wrote into his novels were subsequently reflected in the more mature paintings he produced in Paris and London (1952-60) and in Kathmandu after he and his wife Manu settled there in 1961.

In Bangdel’s search for individuality and identity, Dina writes, “he found distinctiveness in his own ethnic background, particularly through the portrayal of the Nepali people and their social conditions.” She also notes that preoccupation with the themes of poverty and misery in his paintings “derived from the same inspirations as were those in his novels. In fact, the difference between his writings and paintings was only that of the medium; in terms of theme and mood, the message was the same.”

Today, Bangdel’s novels are required reading by students of Nepali literature. They are also recommended for students of the visual arts, as clear examples of a unique talent that produced art in the form of literary realism.

…to draw in words is also an art which sometimes betrays the slumbering of a hidden force. ~Vincent van Gogh

This article was written for the centenary celebration of the Nepalese artist Lain Singh Bangdel (1919-2002). An adaptation of it will appear in a forthcoming book about Bangdel’s life, family, and art edited by Bibhakar Shakya, Deven Shakya, and Liesl Messerschmidt. The book will also include a select gallery of his paintings and tributes to his wife Manu and daughter Dina from colleagues and friends.

Bangdel’s three novels will soon be available in English translation; meanwhile, short descriptions are given in Against the Current: The Life of Lain Singh Bangdel (Messerschmidt, 2004). Besides the biography, parts of this article were also adapted from Lain Bangdel: Fifty Years of His Art by Dina Bangdel (1992), and other sources.