Sitting on an iron bench propped against a wall below the stairs of a temple in Patan Durbar Square, legs crossed, and hands over his walking stick, a fluff of long, white hair coming out of the traditional Nepali dhaka topi he is wearing, Lok Bahadur Shakya basks in the sun in early December, carrying the contended and confident look of a man who has passed many summers and winters. He has already crossed eighty-seven winters, and he finds a gigantic gulf in the winters of yesteryears from those of today.

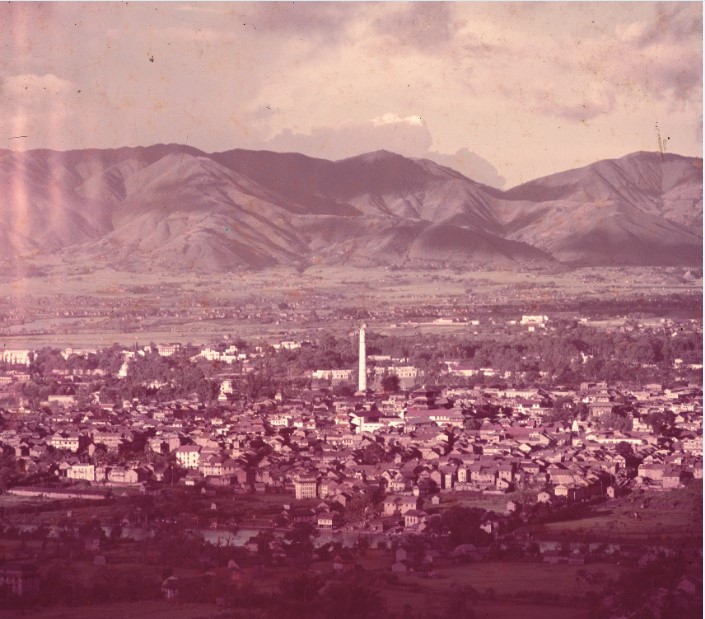

"Compared to what winters were like, you can't even call this cold," he says, as his 82-year-old friend, Saila Shakya, nods in approval. In a clear, confident tone that can only come from experience, he tells me of winters in Kathmandu when it would be shrouded in thick fog in morning, veiling everything that lay beyond a meter or two. Gesturing with his hands, he recalls stretches of fields and grounds covered in frost, and thin layers of ice on the surface of small ponds in Kathmandu Valley.

"If you kept a bowl of water outside at night, you'd wake up in the morning to find the water frozen," he says, reclining his head towards me, seeming to ask if the example succeeded in making me reckon how chilly Kathmandu winters used to be. Not only individuals from these two octogenarians' generation, morning frosts and fogs are etched in the memories of those as young as the millennial generation. They also remember winters that were longer than those in recent years. Raju Kapali grew up in Tahdhoka, on the periphery of Patan core, in the early eighties. Chill pervaded the Kathmandu air as early as Dashain, which falls in the Nepali month of Asoj (September-October), he recalled. "Our mothers dug into the tin trunks just around Dashain came around," he says in a tea shop in Pulchowk. "They wouldn’t let us running about to fly kites without wearing sweaters."

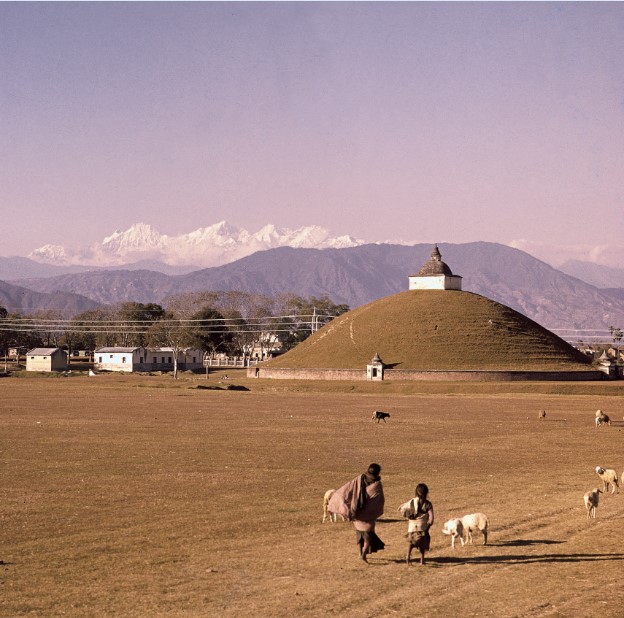

Temperatures dipped each subsequent day after Dashain, and with the onset of Paush (December-January) commenced the coldest period of the year. It would be so freezing during this time that, as the story goes, even fishes deep under the waters felt the chill and hid under the rocks for fifty days to protect themselves from the cold. This is what the terminology minpachas refers to—min means fish, and pachas means fifty in Nepali—so, minpachas means the coldest time of the year, when even fishes feel the cold!

You enter a conversation with someone in their forties or older about their school years, and most likely, the conversation would not end without them mentioning minpachas, which was used to refer to the fifty-day-long winter vacation schools in Kathmandu Valley and some other parts of the hilly region provided. This was a much-awaited yearly event, mostly associated with the spirit of leisure, adventure, and excitement. As students wrote their final exams in the first week of Paush, they found some relief from the stress due to the anticipation of minpachas beginning right after the exams. Almost all schools closed for the vacation in mid-Paush that extended all through the month of Magh (February-March).

As all lifestyles and elements of culture are, the tradition of minpachas was rooted in climatic, social, and cultural contexts of Nepal decades ago, and embodies special cultural and social value. How and when it started, what were its social meanings, and how this practice ended, are some important issues that could provide insights into the social, political, and cultural milieu of the bygone years.

Education was indubitably one of the areas to suffer most during the 104 years of Rana oligarchy that lasted until 1951 in Nepal. A few Sanskrit schools were scattered about the country in the name of formal education. Except for a few comparatively well-equipped schools like the Durbar High School, students studied in decrepit huts, or on mats spread on open ground, or traditional Newari resting places (falchhas). In winter, the cold became too unbearable to continue school activities.

For students who were kept under strict discipline under the teacher’s unforgiving eyes for the entire year, minpachas offered freedom. Depending on generation and the socio-economic class, people valued and spent the holidays differently. Bhairab Risal, 87, Nepal’s senior journalist, was born in Dhadhikot, a village on the foothills along the border of Bhaktapur and Lalitpur. He says, “Even today, the villages on the outskirts of the Kathmandu city have much colder winters than the city. This was much more the case when we were children."

Most people in the kaanth, as the villages dotting Kathmandu’s core are called, like Risal's village, lived hard lives, mostly relying on subsistent farming. “Our teachers and parents worried that we might run astray and deviate from studies during this long recess, so we were asked to go to our teacher’s house to read,” adds Risal. Walking seven kilometers to one of his teacher’s home in Badikhel, and walking back seven kilometers again after classes, is one of his major minpachas memories.

Another prominent memory he carries from the minpachas holidays is of sitting around the ageno, a traditional Nepali fireplace. When temperature plunged with dusk, after dinner, Risal's family huddled together around the ageno. Far from Risal's village, in the city area, too, the sight of people sitting around a fire was common. Even during the day, people wrapped in blankets would be seen clustered around fires in the streets, while stacks of firewood were put on sale in every shop, shares Lok Bahadur. Risal told me that winter in those days tested your endurance, because people lacked enough clothes to keep themselves warm.

The Adventure and Excitement of Minpachas

Over generations, the general hard times associated with minpachas dissipated, and adventure and excitement overbore the hardships of the cold. By the time of my father’s generation, in their late fifties now, minpachas was already a time when peers planned travel and adventures in advance. He and his friends and cousins living in Kathmandu’s core hiked to Shivapuri, Chandragiri, Pulchowki, and other hills surrounding Kathmandu. When the day was brighter and warmer, they went swimming in Bagmati, Bishnumati, or other rivers in the valley that then ran large and clean. In some vacations, they also traveled to Gosainkunda in Rasuwa and Manakamana Temple in Gorkha.

Manakamana Temple and Gosainkunda were, in fact, popular travel destinations during the holidays. Jitendra Baidya, who grew up in Chabahil, remembers that students planned for these trips even before the holidays started. The 51-year-old details that it was more common to take a combined trip including several places—travel to historical Gorkha, then to Manakamana Temple, and then finally to Pokhara.

While older teenagers anticipated travels and tours, the children excitedly waited for the long break, which for them was a season of games. The games children indulged in certainly depended upon specific regions and locales, but some were common. "Marble season," Raju Kapali exclaims, excitement of recalling the marble days visible in his eyes. In courtyards, in alleys, in footpaths, sights of children preoccupied in aiming marbles were common. And, when schools reopened, children bragged about how many marbles they won. By that time, the tips of their fingers would have the skin peeled off, and the back of their hands dried after being exposed to the cold.

"Coincidentally, it was just the minpachas when children played marbles," he shares. "The marbles that came out with the start of the holidays mysteriously disappeared the moment the holidays ended. Children in the countryside had more options when it came to games and adventures. Growing up in a village in the southern end of the valley, my father and other children hunted for fruits like lapsi, or when the sun was shinier and warmer, went for a bath in the stream. Or, if they desired to have more adventure, went to the jungle, stealthily, lest their parents found out.

For 55-year-old Rabindra Man Joshi and peers from his locality, the holidays meant days of fishing. Like Baidya, he was born and grew up in Chabahil, then a small village dotting the banks of Bagmati. Fishes were abundant in the fresh and clean Bagmati waters. For Joshi and his mates, preparing fishing lines and catching fishes was a favorite minpachas event.

He feels that when it comes to minpachas, perhaps no children were as much privileged to experience the adventure that he and his friends did. The airport in those times was more like a grazing field for cattle that were cleared when a plane landed or took off. With the core airport area only bounded by wire nets, it was easily accessible for common people. And, getting across the wire nets to the airport was one of the favorite activities expectantly waited for by Joshi and his peers. There in the large garbage bins, they dug through its contents little things that could make prized keepsakes for children. They mostly sought after empty colorful packets of cigarettes thrown by foreigners. On occasions, the hanger would be open, as well as the plane inside. The children climbed into the planes and hunted for chocolates and toffees and their bright wraps.

Picnics were another happening during minpachas, providing both a day out and an opportunity to bask in the sun. Godavari, Sundarijal, Thankot, and Nagarkot were popular picnic spots. While friends organized picnics among themselves, this was also a communal event, organized by a group of families of a certain locality.

With all the 'out-of-home' events minpachas motivated, it was also the moment of family reunions. If you ask anyone who grew up in the eighties, or before, about their visits to maternal homes, they are most likely to tell that these happened during this holidays. In Nepal's context, maternal homes are mostly located far away from homes. So, the vacation was opportune moment for children to visit their grandparents and cousins.

Many denizens of the valley had agricultural farms in the Terai then. Every year in minpachas, these families moved to their farmhouses. Acclaimed Nepali composer and director Yadav Kharel, 75, has shared in his various media interviews that his family traveled to their house in Nargho, in Saptari, to spend minpachas. As the schools in the plains would be running, he enrolled in a school and studied until the holidays.

While the adventure, excitement, and anticipation that minpachas offered to students away from their books, the holidays itself offered reason to celebrate books and academic spirit. As the new academic session started after the holidays, students waited with excitement to begin the next class. Jitendra Baidya explains that, in those days, unlike today, all schools had the same books. Most students sold books to their juniors at half the price that had cost them the year earlier when they bought them from seniors.

While in the academic year, the teachers constantly nagged students to focus on their books, this role shifted at least momentarily during the minpachas. "The new books, and the anticipation of going up to a new class, enthused us so much that we sought our teachers, asking them to help us read the new books," Baidya says. Children pursued the buy and sale and displayed their new possessions with a festive spirit.

It is these celebratory, romantic, and adventurous spirits of minpachas that have mostly remained in the imaginations of those who experienced it, and in those who have learnt about this from the former. What is almost entirely unspoken about it is the sad reality underlying this long winter vacation. The tradition of summer and winter vacations is not only a common, but an essential, component in education institutions, or any other institutions. But, the 50-day-long holiday in the Nepalese context is also deeply interlinked to Nepalis' tough lifestyle and big class divide. Talking to the elderly generation makes evident the underlying cause of poverty that made this holiday indispensible.

Especially, today's septuagenarians and older generations harbor mixed emotions and feelings about minpachas—the excitement of having long holidays blended with the ghastly reality of having to suffer in the cold for lack of warm clothes. In an interview to a digital newspaper, Nepal's known writer and literary researcher Shiva Regmi, 76, remembered how he and his classmate, Nepal's most beloved singer, the late Narayan Gopal, shivered in the classroom for lack of enough clothes, adding that warm clothes was a privilege of the rich only. Slippers, shoes, even socks, were privileges of the small upper class only. Moreover, as most students had open ground for their classrooms, academic sessions were impractical to carry on during winters.

Risal told me that, during minpachas, parents of those times often repeated a Nepali adage—ketaketi ko jado bakhra le khancha—which translates to mean that the cattle takes away the children's cold, perhaps suggesting that more cattle staying close meant more warmth in the surrounding. "As children, we actually believed this," he says. "In retrospect, I feel that the parents repeated this to provide psychological strength to children to face the cold."

One reason for the end of the tradition of the minpachas has certainly to do with Nepali society's increasing resilience to winters. The shift in the academic calendar in the mid-1990s, as well as the rise in the number of boarding schools, which started scheduling their terms and holidays to meet the requirements of students from outside the valley who needed longer breaks during Dashain and Tihar to be with their families, are also other reasons for slashing the winter holidays.

There were political and social causes also. The political uncertainty that dawned in Nepal after 1990 severely impacted educational institutions with political strikes, which were sometimes directly aimed at education institutions, disrupting the academic calendar. Hence, many forced closures compelled schools to cover up by slashing holidays. Addition of other individual holidays related to events and festivals of various ethnic and indigenous groups after 2006 also led to the cut in winter vacation. And, of course, winters in Kathmandu are getting warmer, owing, among others, to rapid urbanization and air pollution.

Perhaps, what better affirms this strong impact is the choice of the title "Min Pachas Ma" (translated as "During Min Pachas") of a 1995 album by Nepal's most popular musical band, Nepathya. The title evokes memories of minpachas. It also reaffirms the cultural importance the holidays had as a time of happenings for generations of Nepalis.