A run-in with an enterprising grandma moonshiner in Kirtipur results in a bottleful of brew with a kick that takes the writer on 20 km walk to Bhaktapur.

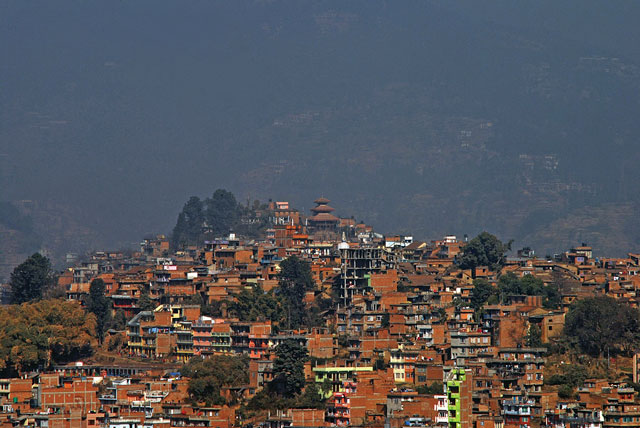

The nooks and crannies of Kirtipur felt silent, with not a soul in sight. Barely audible metal clanks, revving tractor engines, and indistinct chatter seemed distant. Under the warm winter sun, inescapable siesta was perhaps culpable for the deserted streets. I walked around, enjoying take-away bara to appease a growling tummy, and a bottle of Coke to quell that sugar craving, keeping a later professional rendezvous in mind. I swung the empty coke bottle in the air, walking up towards Uma Maheshwar Temple atop the hillock looking for a trash can.

As I walked up the dodgy cobbled alleyways, it would take the most harmless action of carrying around an empty plastic bottle to discover Kirtipur’s cheeky secret. Little did I know that an aimless stroll along the streets of the old town would result in a monumental intoxicated march to Bhaktapur. For, in the midst of silence and calm, came a low pitched summon, “Oh, baucha!” I heard an aged voice calling me from somewhere in the endless row houses that surrounded me. “Oh, baucha,” she called again. I looked up to barely make out a grandma-figure hidden behind flower pots on the roof, making gestures I couldn’t comprehend.

As I walked up the dodgy cobbled alleyways, it would take the most harmless action of carrying around an empty plastic bottle to discover Kirtipur’s cheeky secret. Little did I know that an aimless stroll along the streets of the old town would result in a monumental intoxicated march to Bhaktapur. For, in the midst of silence and calm, came a low pitched summon, “Oh, baucha!” I heard an aged voice calling me from somewhere in the endless row houses that surrounded me. “Oh, baucha,” she called again. I looked up to barely make out a grandma-figure hidden behind flower pots on the roof, making gestures I couldn’t comprehend.

“Hajur?” I duly replied.

I looked more closely, and saw she was giving me a repeated and frantic thumbs-down. Perplexing, to say the least.

“Hajur?” I asked again, confused.

She wasn’t speaking; she just moved her lips and gave a thumbs-down, almost as if she didn’t want anybody else to hear.

“Say it out loud,” I said.

“Raksi halne ho bhanya?” she finally shouted aloud, almost getting annoyed. She was offering me a batch of her homemade moonshine.

Now for a little background. The moonshine in question is raksi, a clear but slightly murky triple-distilled millet based local brew, rather tough on the nose, but surprisingly smooth on the throat. Though technically wine, there’s nothing Victorian about it, especially considering the way it’s drunk traditionally from dirty tiny tea cups, or straight out of jerkins (Nepali for jerry cans) by bandsmen at weddings, followed by primal grunts of approval over sittan, or munchies, comprised of bone marrow extract and medium-rare brain matter, along with deep fried innards and chewy goat testicles, to name a few popular delicacies raksi goes well with. The drink is served in almost all Newari festivals and social gatherings, and often consumed as God’s offering. Also called tharra, tin-pane, and solmari, the drink comes in several varieties, depending on ingredients added, yet the essence and spirit of the drink remains the same. Revered as it is during festivals, it’s interesting, though unsurprising, to note that raksi gets an unfavorable rap among infuriated wives waiting for their husbands to return home from late night debauchery in bhattis serving said spirit discreetly and less-than-legally so.

Now for a little background. The moonshine in question is raksi, a clear but slightly murky triple-distilled millet based local brew, rather tough on the nose, but surprisingly smooth on the throat. Though technically wine, there’s nothing Victorian about it, especially considering the way it’s drunk traditionally from dirty tiny tea cups, or straight out of jerkins (Nepali for jerry cans) by bandsmen at weddings, followed by primal grunts of approval over sittan, or munchies, comprised of bone marrow extract and medium-rare brain matter, along with deep fried innards and chewy goat testicles, to name a few popular delicacies raksi goes well with. The drink is served in almost all Newari festivals and social gatherings, and often consumed as God’s offering. Also called tharra, tin-pane, and solmari, the drink comes in several varieties, depending on ingredients added, yet the essence and spirit of the drink remains the same. Revered as it is during festivals, it’s interesting, though unsurprising, to note that raksi gets an unfavorable rap among infuriated wives waiting for their husbands to return home from late night debauchery in bhattis serving said spirit discreetly and less-than-legally so.

That brings us to our next point: raksi can only be produced and consumed for personal use, and can’t, technically, be sold commercially. Hence, the thumbs-down in Kirtipur turned out to be granny’s cryptic gesture to fill the empty Coke bottle with raksi. Epiphany!

I had no reason to decline the non-conformist grandma’s offer, and happily played along. “Thaana waa,” she ushered me down the street, and into a quarter well hidden from Big Bro’s watchful eyes. It was her micro brewery, a secret lair in a shabbily kept hall of an abandoned construction site. Not a brewery you’d imagine with mile-long conveyor belts, skyscraping smokestacks, and an army of blue collar workers a thousand strong. But, rather, we walked into the lady’s beau, her partner in crime, stirring metal pots stacked up on a firewood furnace. A giant drum in the corner, meanwhile, steamed off freshly prepared raksi that smelled like sweet heaven.

“How much do you want?” the lady asked.

“To the brim,” I replied adventurously, trying to reinforce her idea of the maverick of a drunkard she assumed I was. I dropped a meager Rs. 80 for the bottleful of authenticity and fun I walked out of the distillery with.

I sat on the ledge by Uma Maheshwar, the highest point of Kirtipur, and soaked in the good vibes. Over swigs of the handcrafted spirit, the bird’s eye-view of Kathmandu from the temple couldn’t have gotten any better. The lovely taste complemented the ambience, the sights, the breeze, and the peace. Little by little, I felt thrown into what could be called a state of trance, until I realized the bottle was almost totaled, and that I had a meeting to attend in Bhaktapur some 20 km away. I downed the last gulp, and proceeded to stand up, only to discover that the mellow taste of the spirit was a far cry from the punch it packed. The world in front spun and instantly put me back on my throne, giving me a reality check. I got hold of myself, though barely, and in an attempt at sobriety, embarked on an epic journey to Bhaktapur—on foot.

Long story short, a few hours later, I found myself struggling hard to hold a straight face at the meeting, which thankfully (after what felt like forever), concluded without arousing suspicion. In a poetic justice of sorts, sandwiched between bleating, constipated goats and compatriots reeking of the same spirit on a bus back to Kathmandu was no laughing matter. The inconspicuous run-in with Kirtipur’s grandma took its toll and sent me to bed with a promise, albeit in retrospect a short-lived one, to never again touch raksi.