The intriguing painting of a belly-protruding Mahadev

I have seen Indian soldiers patrolling the area around my house in 2017 BS (1961),” he says. “That was when the first movement for democracy succeeded in bringing multiparty politics into the country. Since then, I have never trusted the multiparty system.” It must have been a bitter pill to swallow for an intellectual of his kind. “And, in 2046 (1990), while people celebrated the return of multiparty democracy, I retreated into a shell.”

Manuj Babu Mishra, an artist and literateur who is held in the highest esteem by intelligentsia nationally and internationally, has now thus lived indoors for almost 10 years. “It is not that I am a royalist, it is just that I do not like this multiparty system at all.” He will be 75 years old in August. “There are some in Germany and Italy who celebrate my birthday every year on 13th August,” he says proudly, but adds, “Actually I was born on Janai Purnima Day.”

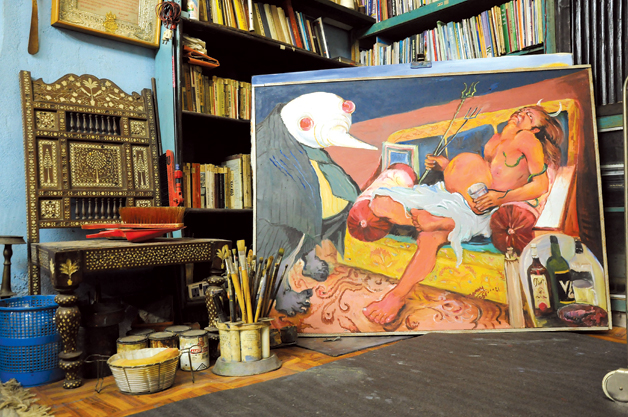

His abode is in on the way to Teen Chule on Pasang Lhamu Road in Bouddha. Fittingly, it is called the ‘Hermitage’. Actually, a hermit is what he likes to call himself. He lives in an old cottage which has one long room with tall shelves crowded with all sorts of books, an alcove holding his finished paintings, and a small room divided by a make-do curtain that serves as his bed room. A bathroom is next to it. As expected, there are lots of colorful canvases hung on the walls. His working table too looks pretty crowded with all sorts of things. He sits down on the carpeted floor and takes a sip through a plastic pipe attached to a large bottle that is half full with water. “Easier this way,” he says. “Especially when I’m painting.”

Clearly, Mishra likes to display his eccentricity - one that he has taken pains to develop. “I live here, sleep here,” he says. “My wife Ramola lives in the house across the garden.” Mishra has two sons and a daughter who are living separate lives. One, Ravindra Mishra, is a BBC correspondent, the other, Roshan, is in London working as a computer animator and the daughter, Manju, is the founder principal of the country’s first college of mass communication and journalism.

He might call himself a hermit, but actually, he is far from being one in the real sense of the word. For one thing, he lives in a veritable Eden. The expansive garden is chok-a-block with trees and plants of every hue and color. One will finds lots of different fruits growing on many trees at any time of the year. Mangoes waiting to ripen, hang heavily from tired branches; pears too can be seen in abundance as can ‘jamuns’, small pale green fruits that have a fragrance similar to jasmine and tastes delicious (the artist himself plucked a few for us with the aid of a long pole with a hook at the end). Grapes, persimmons, apricots and figs - the hermit indeed has taken care to surround himself with the bounties of nature!

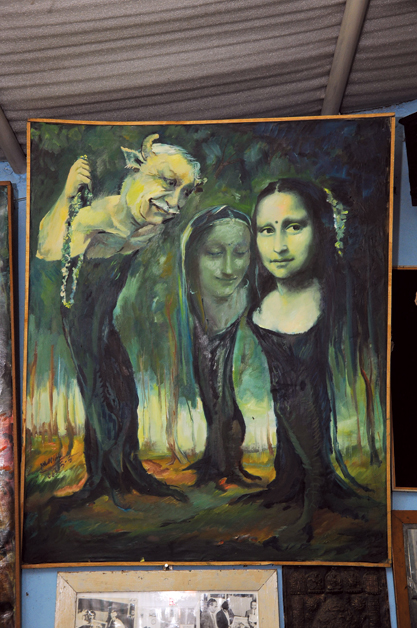

Mishra's Mona Lisa muse

Mishra is originally from Gorkha . An old photograph in black tie and suit attests to the fact that he was a handsome specimen of Nepali manhood in his younger days. The highlight of his once ordinary life was when he became a deputy secretary in government service. “I left the service after three-four months,” he says. “I realized that signing papers all day long was not my forte. I believed I was meant for something different.” His wife brings us cold curd water drinks. Mishra smiles and says, “That was the first time my wife cried.”

Frankly, I am more than a bit intrigued by the nature of the man. I want to know more about his lifestyle. “I go to sleep between 6:30 to 7 pm. I wake up at 2 am,” he discloses, adding, “This has been my habit since the last 10 years.”

So, what does he do whole night long? “I sketch, paint, write. Sometimes I just stare at the ceiling!”

He shows me a couple of heavy sketch books. “There are plenty more,” he says. Flipping the pages makes one engrossed. His sketches are mesmerizing. They are clearly the works of a master. “It will take you days to go through all my sketches,” he says. Mishra uses sharpened bamboo tips dipped in ink to draw his sketches. A smaller pad is like a pictorial encyclopedia of Nepal’s who’s who. It contains sketches of many of the country’s well known artists and literateurs. “They are all autographed,” he points out.

Mishra is relatively fit for his age but does complain, “I can’t walk around much. It’s my back.” Sitting down on the carpet in his room, however, he appears to be comfortable enough. He points to the sofa I’m sitting on and says, “You know, once I imagined Lord Mahadev to have come here in the dead of night. He slumped down on that very sofa. He was exiled from his temple in Pashupati and so had come to take refuge.” He points to a large painting at one corner. It shows a belly protruding Mahadev sprawled on the sofa. He is obviously drunk - there are some empty whiskey bottles beside him. A suited figure with a white oval head and a beak is staring down at him. I ask, “What is that figure?’

“He is one of those who exiled him, what do you think?” This painting was done around the time of Gyanendra’s ousting from Narayanhiti Palace. “You will see a lot of ‘dinosaur’ like figures in my paintings. They are dinosaurs assaulted by my ego. "

His ego? Well, it is a fact that many, if not all, of his works have wide (wild) eyed - some very much devilish - faces of the artist himself. One painting in particular is especially interesting. It shows the artist painting a full length nude figure of Venus (‘Boticelli’s Venus’, he informs). The artist’s silver hair is twisted at the sides to resemble horns and he has a gleeful look on his face. In short, he seems to be really enjoying himself! A couple of other paintings have Mona Lisa (some ethnically clad) as a central figure. What’s this obsession with ML (mysterious lady)? Well, there’s a tale behind this too.

“Once I was assigned to paint my version of Mona Lisa for a European connoisseur. The painting, after it was finished, stayed here for some time before being taken abroad. Once it was gone, I felt a void in my life. I was used to looking at her every day. To fill this void, I have made Mona Lisa an integral part of many paintings.”

Mishra’s works are rowdily extravagant in nature and it is clear that they are no-holds-barred efforts. But, a better explanation of his style can be understood from a statement in ‘In the Eye of the Storm’ published in 2009 by Nepal Investment Bank, kind courtesy of its Chairman, Prithvi Bahadur Pandey: ‘The basic concept of my work regardless of the media I use, are the result of, and a reaction to, the churnings of my mind.” These are actually words vague enough to mean anything. But it must be said that the artist paints for himself, and only for himself which, looking at his lifestyle, can be said to be characteristic of the man. In fact, one has to ask, ‘How else could it be otherwise?’ He writes on the back page of his printed resume, ‘One’s mind is full of ideas, experiences and knowledge. If you are over burdened by ideas in mind it will be difficult even to live … Art for me is inner expression to vacate the inner load of mind.’

Clearly, Mishra is a ‘been there, done that’ kind of man who has realized that no matter how big or how populated the world is, one has to live a life that is in reality within oneself. Fame has become his companion and perhaps the nine feet tall statue of the legendary Arniko in his garden is a constant reminder to him, the hermit, that he himself stands several inches taller than the normal man. “You won’t find a comparable statue of Arniko in Nepal,” he says. “I had it built myself.” It’s an impressive statue, no doubt about it.

Much smaller but no less impressive is a small (one could almost say, a miniature) well framed painting in his room. It is a full length portrait of his father, Tulsi Singh Mishra, snappily dressed in a daura suruwal, waistcoat, coat, and Bhadgaunle cap. Mishra declares, “I wouldn’t sell that painting for even 20 lakh rupees.” Why? “It is one of the only remaining works of Anand Muni Shakya and was painted a hundred years ago!” He elaborates, “Anand Muni was the son of Siddhi Mani Shakya, one of the greatest artists of Nepal. He painted the 108 figures on the first floor of the famous Akash Bhairab Temple.”

The hermit is a knowledgeable man and he bandies about names of famous Europeans with ease. He has travelled to all corners of the globe. In the process, he has made many friends and collected quite a number of artifacts. Among them are some ancient Roman coins and, “I also have a 25000 year old jaw bone of a dinosaur!” On a table are some expensive looking glossy art books. “My European friends often send me gifts like those,” says Mishra. He himself has written 20 books, one of which has been translated to English. “It’s called Dream Assembly,” he says.

The artist himself

Mishra is an atheist through and through, a trait perhaps handed down from his father who was likewise one. “For me, if I have to say it, then the late king Mahendra, was a god.” One notices the late king’s photos around the room, some on old calendars. It must be surmised that the hermit has quite a few definitive opinions. And these opinions are not based on outdated information and knowledge only of the yesteryears. A stack of newspapers in the room, added to a radio and many magazines on the table, make it obvious that he keeps up to date with the goings on around the world - another feature of his lifestyle that makes it difficult to believe that he is really living the life of a hermit, as he claims to do.

All this however, is a moot point when you consider his abilities and his dedication to art. I ask him, “Don’t you think it would be a good idea to have a permanent museum of your works? One, where art lovers and students of the craft can come and view your canvases?” His answer is succinct, “You can listen to music anywhere. You can watch movies on television and cinemas. To see art you have to go either to exhibitions in galleries or you have to visit the artist’s place of work. For those who want to see my paintings, they can come here anytime. All are welcome.”

Manuj Babu Mishra may not be as completely a hermit as he tries to be, but he definitely is an oddity. And that is how Sangeeta Thapa, who edited the book, ‘In the Eye of the Storm’, describes him, ‘Manuj Babu Mishra is both an oddity and an icon on the contemporary art scene in Nepal.’