The Chinese Connection

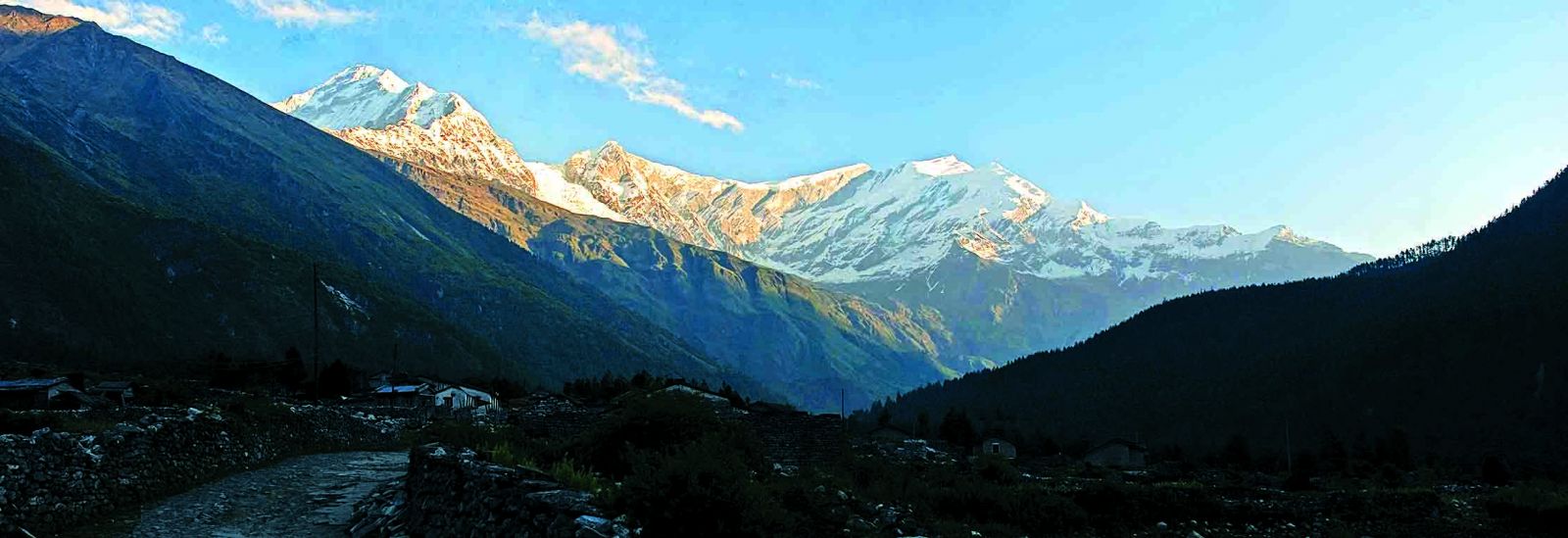

Nepal and China are linked by the mighty Himalayan range, and since time immemorial the relationship has been as enduring as the majestic peaks.

Nepal is now, officially, a partner of the One Belt One Road (OBOR) initiative, China’s historic plan to revive the ancient Silk Road trade routes. Spanning some 65 countries, this massive infrastructure project is certain to result in super-connectivity between nations and fantastic commercial opportunities. This grand vision was introduced in 2013 by Chinese President Xi Jinping, and on February 15, 2016, the first train dispatched under the initiative arrived in Tehran from Zhejiang Province of China. In January 2017, the service sent its first train to London, which connects onward to Madrid and Milan.

If you think about it, the OBOR is pretty similar in concept (on a different scale, mind you!) to one of our very own grand visions—the Great Himalayan Trail (GHT), a network of connecting trails stretching across the greater Himalaya region. About 2,800 km long, the GHT, in its entirety, passes through Nepal, China (Tibet), India, Bhutan, and Myanmar, passing under the shadows of the world’s highest peaks, all fourteen of the eight-thousanders (peaks 8,000 m and above). The 1,700-km-long Nepal section stretches from Taplejung in the east to Darchula in the far-west, and is divided into ten connecting treks, with two routes available—the high route (3,000 m-5,000 m) and the low route. The Nepal section of the GHT was completed for the first time in 2008 and 2009 by Robin Boustead and his team in 162 days, while the first commercial trek was completed in 157 days in 2011, from February to August.

In a manner of speaking, Nepal can claim to have at least something in common in recent times with its giant neighbor—a vision as grand in its own way as that of China’s OBOR. It is not that these two countries.—one a giant covering an area of 9.6 million square kilometers, with a population of about 1.40 billion, and the other covering some 147,181square kilometers with a population of about 29 million—do not have more in common. In truth, we have had a lot to share since the ancient days—since as far as back as the beginnings of Buddhism as a world religion, and the era of architect, artist, and sculptor Arniko and Emperor Kublai Khan.

Arniko, Liang Guo Gong and Architect Extraordinaire

Let’s go back to the year 1260. That was when Kublai Khan, the great Mongol Emperor, ruled over China. He was a faithful disciple of Chos-rje pa Sakya, a spiritual teacher he especially revered. After his death, Kublai Khan ordered his current spiritual teacher, Lama Phags-pa, to have a golden stupa built in Lhasa to honor Chos-rje pa Sakya. It was not as easy task, given the paucity of good architects in the country. However, relations with neighboring country Nepal was excellent at the time, and so Phags-pa sent an emissary to the Nepali king, Jaya Bhim Dev Malla, requesting him to send a capable architect.

The king, in turn, ordered Arniko, a young sixteen-year-old lad who was gaining quite a reputation for his architectural and artistic skills, to gather a team to go to China. In due time, eighty artisans were on their way to fulfill their important task. At the end of it, the Emperor was so pleased with their work that he had Arniko summoned to his court, not only to congratulate him, but also to test him further. The young man was asked to restore a metal statue, an important gift from a Song emperor, to its former glory, which the court artisans had declared to be beyond repair. Arniko took up the challenge and restored the statue to its original perfection, although it took a very long time. Kublai Khan was impressed, to say the least.

Thence on, the young Nepali architect was commissioned many works all over China. These included the White Pagoda (a.k.a. White Dagoba) of Miaoying Temple in Beijing, which became his most famous work. It took him eight years (1271-79) to finish it, but it was well worth the time and effort (it was declared a national treasure by Premier Zhou Enlai in 1961 thus saving it from the ravages of the Cultural Revolution). Other notable works included one Taoist palace, two Confucian shrines, nine Buddhist monasteries, and the Archway of Yungtang. Arniko was a great painter, as well, and his portraits of Chinese emperors were much admired.

He was conferred the title of Liang Guo Gong (Duke of Liang), became a minister in the emperor’s court, and was awarded 15,000 acres of farmland, 1,000 serfs, and 100 cattle. His biography is included in the history books of imperial China; a unique feat, considering the rarity of foreigners so featured. By the time of his death in 1306, at age sixty-two, Arniko had disseminated Nepali art and architecture all over China and Mongolia, and even to places as far as Indonesia. Doubtless, Arniko played a very important role in developing mutual respect between Nepal and China, and fittingly, in 2010, the Nepal Arniko Center of the Nepal Pavilion at the World Expo Park of Shanghai was the center of attraction for thousands of visitors.

Buddha’s Blessings

Yes, Arniko achieved what many others couldn’t do; he earned great name and fame even in a country like imperial China, where outsiders were generally looked upon with disdain. So, it is most apt that a statue of him stands proud in Miaoying Temple, Beijing, a worthy symbol of Nepal’s significant role in a part of China’s cultural history. However, the connection between China and Nepal goes even further than Arniko and Kublai Khan.

The ancient Silk Road was established during China’s Han Dynasty (BCE 202 – CE 220), linking different regions in commerce. It stretched from China through India, Asia Minor, Mesopotamia, Egypt, the African continent, Greece, Rome, and Britain. Today, there are over 40 countries alongside the historic Land and Maritime Silk Roads. The maritime routes, linking the East and the West, were used mainly for the spice trade, and so were known as the Spice Routes.

The routes were also instrumental in disseminating religious beliefs throughout Eurasia, and this included Buddhism, which spread all over Asia, with Mahayana, Theravada, and Tibetan Buddhism being the three major schools. Chinese pilgrims traveled on the Silk Road to India to acquire Buddhist scriptures. Because of its cultural significance, aside from the commercial aspect, UNESCO listed the Silk Road as a World Heritage Site on June 22, 2014.

One has to go back as far as the seventh century. That was when Songsten Gampo, the king of Tibet, was wed to Bhrikuti Devi, a princess of Nepal, who brought along with her sacred texts of Buddhism and images of Buddhist deities like Akshobhya Buddha, Tara, Maitreya, and Avalokiteshvara. Together with the king’s Chinese wife, Wencheng, a devout Buddhist herself, they built imposing landmarks like Jokhang and Potala Palace in Lhasa, as well some temples in Bhutan. Thus was Buddhism introduced in Tibet, and it was further entrenched during the reign of King Trisong Detsen (755-797).

Now, enough of ancient history, let’s come back to present times. Here’s something interesting I discovered on Wikkipedia (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Buddhism_by_country) – “China is the country with the largest population of Buddhists, approximately 244 million.” Did you know that? I certainly didn’t. So, back again to history to know why—apparently, the first Buddhist scriptures came to China during the time of the Han Dynasty (B.C. 206 - 220 A.D.), and the religion took hold in a big way. Buddhism certainly has a long history in China, so is it any wonder that the connection between China and Nepal has been so enduring down the ages? A connection that surely has the blessings of Lord Gautam Buddha, who was born in Nepal, and is as revered in China as he is here.