Forty years after the first human conquest on Everest in 1953 by Tenzing Norgay Sherpa and Sir Edmund Hillary, the world’s highest peak was still an untouched territory for Nepali women. By 1993, 16 female mountaineers from different countries had already broken stereotypical barriers by setting foot atop 8,848 metres defying the male-dominated mountaineering expeditions. However the country that was home to the mountain was still cold to its own women — no Nepali women had so far stood atop Everest. History was waiting to be written. It still was a feat for most of the Nepali men as well.

On April 22, 1993, 31-year-old Pasang Lhamu Sherpa accomplished what no Nepali women, and only a few Nepali men had in the country’s mountaineering history — against all odds, she became the first Nepali woman to summit Everest.

Reports of Pasang Lhamu’s notable summit success circulated the country’s mainstream media. But it was rather short-lived. The days that followed then focused on the disappearance of the first Nepali woman who until a few days had stood on top Everest. 18 days later, on May 10, her body was found — she lost her life on her descent at South Summit due to unfavourable weather conditions in the high altitude.

Reports of Pasang Lhamu’s notable summit success circulated the country’s mainstream media. But it was rather short-lived. The days that followed then focused on the disappearance of the first Nepali woman who until a few days had stood on top Everest. 18 days later, on May 10, her body was found — she lost her life on her descent at South Summit due to unfavourable weather conditions in the high altitude.

An ordinary individual from an ethnic Sherpa background suddenly became a household name in Nepal. The saga of Pasang Lhamu’s life and death added a new perspective to women’s role in Nepali society. For a country that was undergoing a socio-cultural revolution, for many girls growing up during that time, Pasang Lhamu’s feat would become a milestone – they would later learn about her in their school curriculum and also aspire to follow her footsteps.

Almost twenty years later, it did turn out to be that way. It seems the first Nepali woman mountaineer had inspired a generation.

Twenty-nine-year old Chhurim Sherpa grew up in the shadows of the Himalayas. While helping her parents in running their family guest house, she often looked at the trekkers passing by her village in Taplejung district, gazed at the snow-capped Himalayas and dreamed that one day she would also carry a backpack and go trek.

Twenty-nine-year old Chhurim Sherpa grew up in the shadows of the Himalayas. While helping her parents in running their family guest house, she often looked at the trekkers passing by her village in Taplejung district, gazed at the snow-capped Himalayas and dreamed that one day she would also carry a backpack and go trek.

But it was Pasang Lhamu’s story that she came across as a fifth-grader which sowed an interest in young Chhurim.

“I didn’t think a woman was capable of getting there,” she said reflecting her childhood thought. “After reading her story, I just thought one day I might as well be there. After all, I was interested in adventure.”

In May 2012, Chhurim stood at the peak where her icon once stood, and she did it two times setting a new record to climb the world’s highest peak twice in a week.

“I really want other Nepali women to get involved in mountaineering,” she said expressing her dissatisfaction towards the lack of women’s participation in this field. Out of the 219 women who have climbed Everest so far, only 21 are Nepalis, and Chhurim wants that to change.

And so did Pasang Lhamu.

In a file footage video that is now a part of a documentary highlighting her life, Pasang Lhamu reiterates her romance with the mountains. And a belief that, she like the ones who summited the highest mountain, could do the same. Having attempted Everest three times before she made it to the top, she just didn’t want to give up. She had already summit Mt. Mont Blanc in France and Mt Pisang and Yala Peak in Nepal.

“So far, 16 women from different countries have climbed [Everest],” she says in the footage of the documentary The Glass Ceiling. “It feels sad that despite the peak being in our country, no Nepali woman has climbed so far.”

“So far, 16 women from different countries have climbed [Everest],” she says in the footage of the documentary The Glass Ceiling. “It feels sad that despite the peak being in our country, no Nepali woman has climbed so far.”

Her brothers and father speak of her fortitude and strength – one of her brothers say that she was “like a man.” But Pasang Lhamu, instead of proving that she is no less than a man, wanted to establish a new identity for women and becoming a telling example that gender roles could be switched when it came to mountaineering.

“There is nothing that we cannot achieve if we try,” she said at a press conference before her expedition. “I was not born as a mountaineer; I am a housewife. I am trying and hopeful I will succeed. I am doing this to inspire other women.”

Twenty years later, she in fact has inspired young women to breathe the thin air and do something that was once unconventional and was thought to be only reserved for men. Like Chhurim, there are other women mountaineers and maybe male mountaineers alike who have been inspired by Pasang Lhamu.

Asha Kumari Singh and Chunu Shrestha, both in their late twenties, credit Nepal’s first Everest woman summiteer for shapeing up their recent conquests. Singh and Shrestha were a part of the first inclusive women’s Everest expedition in 2008. Since then, along with five other women members, their team of Seven Summits Women are on a mission to climb the highest peak in every continent deliberating the message of girls’ education and women empowerment.

Both women admit that after studying about Pasang Lhamu’s story in their school curriculum, they questioned if they could even dare to do something of that magnitude. But somehow, Pasang Lhamu’s story made a significant impact that today has led them to follow the footsteps of Nepal’s first.

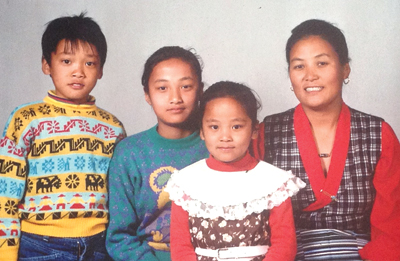

As a mountaineer, while Pasang Lhamu has inspired the future of women climbers in Nepal, as a a parent, she has left her legacy with her three children.

Her eldest daughter Dawa Futi Sherpa remembers her mother as “a woman who dared to dream and reach the top of the world.” It was in fact a dream that defied typical gender realm.

“She has taught me to never be afraid to try,” Dawa Futi says, adding that one day she would also be able to accomplish something that is significant and meaningful to others.

In an upcoming documentary about her mother’s life and legacy, the daughter sketches a picture of Pasang Lhamu as a strong, resolute woman who wanted to climb Everest so she could represent all the marginalised women.

“I think she wanted to be that figure that people—women, children—could look up to and say ‘You can do it,’” Dawa Futi says as she sums up her mother’s quest with moist eyes and a voice choked with emotional drift.

And that was something that Nancy Svendsen, the director of The Glass Ceiling, wanted to tell through the documentary.

Amid a handful of Pasang Lhamu’s family, friends and fans in Kathmandu, Svendsen said that Pasang Lhamu’s story is about overcoming gender stereotypes and making women realise of their potentials.

“In a male-dominated society, as a woman, she did something unthinkable,” Svendsen said of Pasang Lhamu. “The determination, vision and drive – it’s a story that needs to be told. It’s a universal story for men and women, which relates to dreams and determination.”

Anil Chitrakar, a social commentator, said that Pasang Lhamu’s story helps to understand the Nepali society two decades ago.

In the wake of a new-found democracy after the 1990 political referendum, Nepal was embracing strings of socio-political changes, and women’s rights was at the forefront of the evolving social movement. Women were breaking away from the traditional gender norms and Pasang Lhamu’s story evidently represented that shift.

“Future generations will be inspired by her,” Chitrakar said. “She represents a hero.”

A hero in her own rights, Pasang Lhamu has also been recognised by the nation for her attempts and accomplishments. She was posthumously conferred various titles, including the Nepali Tara becoming the first Nepali woman to receive the recognition. The Government of Nepal also issued a postage stamp on her name, renamed the Jasamba Himal as Pasang Lhamu peak and also named a special wheat type as Pasang Lhamu wheat. The Trishuli-Dhunche road has also been named as the Pasang Lhamu highway in her memory.

Twenty years after her death, as the nation commemorates the 60th anniversary to the first feat to Everest, Pasang Lhamu’s name has been etched into Nepal’s mountaineering history. Two decades later, students in their school curriculum closely study her story, either inspiring to be her like or taking lessons from her life.

The new generation of Nepali women who are taking a lead in shaping up the “new Nepal” are a testament. They represent similar hopes and dreams of a woman who is remembered for being the first woman to climb Everest. But it is also important that Pasang Lhamu’s success should be underscored more than from the sole gender perspective – her accomplishments and dreams have inspired a generation, men and women alike. For that reason, she is a true hero.

“She was a fighter and a believer in women’s strength to achieve greatness,” Dawa Futi sums up her mother’s extraordinary characteristic. “Whenever I feel like I cant do something, I always think of her and find strength.”