It is a curious fact of life that sometimes the deepest mysteries lie right under our very noses. Datura is an excellent case in point. A herbaceous shrub with fragrant white or light purple trumpet-like flowers and spiny round seed pods, Datura grows abundantly all over Nepal, and not just in the wild; it has long been cultivated as a garden ornamental but also thrives, much like cannabis, on unkempt wasteland and along riverbanks.

Datura shares its place in the Solcanaceae family with other flowering plants such as Belladona (Deadly Nightshade), Mandragora (Mandrake) and Brugmansia (Angel’s Trumpet). Of the fifteen different species of Datura, two, Datura metel and Datura stramonium, are commonly found in Nepal. Because the plant grows all over the world, it has amassed a prolific number of names. In English alone it is variously known as Datura, Thornapple, Jimsonweed, Prickly-burr, Devil’s Weed, Devil’s Apple, Zombie Cucumber and the Sorcerer’s Herb.

Datura shares its place in the Solcanaceae family with other flowering plants such as Belladona (Deadly Nightshade), Mandragora (Mandrake) and Brugmansia (Angel’s Trumpet). Of the fifteen different species of Datura, two, Datura metel and Datura stramonium, are commonly found in Nepal. Because the plant grows all over the world, it has amassed a prolific number of names. In English alone it is variously known as Datura, Thornapple, Jimsonweed, Prickly-burr, Devil’s Weed, Devil’s Apple, Zombie Cucumber and the Sorcerer’s Herb.

Those rather sinister names give us a clue as to what sets Datura (and in fact all members of the Solcanaceae family) apart from most other attractive flowering plants. All of them contain organic compounds called tropanes, most significantly the tropane scopolamine. In minute doses scopolamine has long been known to have medicinal effects, especially in the treatment of motion sickness and asthma, but in larger doses the effects of this fearsome alkaloid are an altogether different story.

I first read about the use of Datura in a magico-religious context in Nepal in John T. Hitchcock’s seminal work Spirit Possession in the Nepal Himalayas. There it is mentioned in passing in the context of certain tantric rituals of Vajrayana Buddhism. I remember at the time that it piqued my interest but since I neither knew what the plant looked like nor what it was called in Nepali I did not feel that I was in a position to pursue any particular line of inquiry into the matter. It was only many months later, in the unlikely context of reading a Nepali textbook aimed at grade six schoolchildren, that I made the discovery that the English word Datura was virtually the same as its Nepali cognate, dhaturo. In fact, both words are derived from the Sanskrit da dhu ra whose da stem appears to be derived from another Sanskrit word dhat, which usually connotes a poisonous quality. Until recently it had been supposed that the Datura genus was endemic only to the continents of the New World. However, the Hungarian linguist Bulescu Siklos argues convincingly that one particular Datura species was well known on the Indian subcontinent long before the Colombian age, from which time onwards plants endemic to the Americas spread across the world with remarkable rapidity. Siklos writes, “Datura metel, under the name dhattura, has been known in India for centuries. There are references to it in the Amarakosa, Vatsyayana’s Kamasutra and the Matsya Purana, and doubtless also in many more texts.” One of the two Kamasutra references (4th to 6th century AD) advises a man to anoint his penis with honey infused with Datura and long peppers before sexual intercourse to make his partner, ‘subject to his will.’

Siklos’ main focus, however, is on the Vajramahabhairava Tantra, a 10th century AD Indian Buddhist tantric ritual text written in Sanskrit of which only a Tibetan translation is still extant.

Siklos’ main focus, however, is on the Vajramahabhairava Tantra, a 10th century AD Indian Buddhist tantric ritual text written in Sanskrit of which only a Tibetan translation is still extant.

In this translation, a number of passages outline magic spells which involve the use of Datura. One such passage states, ‘Then, if the mantrin wants to drive someone insane, he takes Datura fruit, and, mixing it with human flesh and worm eaten sawdust, offers it in food or drink. He recites the mantra and that person will instantly go insane and die within seven days.’ It is on the basis of these described effects that Siklos proposes that the plant in question is certainly a member of the Solacanaceae family and, to his mind, almost certainly Datura metel.

With the help of a friend I began to search for this mysterious and dangerous plant in Kathmandu. Almost immediately we found copious amounts of large plants growing along the banks of the Bagmati bearing both the trumpet-like white flowers and the distinctive seed pods which have led to Datura being known as the thornapple in English and other European languages. We picked several seed pods for further identification at home using the internet. Our conclusion was that what we had in fact found was Datura stramonium, not Datura metel whose seed pods are noticeably rounder rather than egg shaped. In any case, all species of Datura contain scopolamine and are therefore likely to be used indiscriminately for magico-religious purposes.

The next step was to find individuals with firsthand knowledge of the effects of Datura. Theoretically these people could have been religious members of either Hindu or Buddhist traditions but since the Vajrayana Buddhist tradition is often willfully hidden from the purview of outsiders by those who practise it, I thought it wisest to make inquiries amongst the yogis of the Kal Mochan temple in Thapthali, one of whom I was on relatively good terms with at the time. It is well known that yogis smoke psychoactive plants in order to awaken the shakti of the Kundalini Snake which otherwise remains coiled at the base of the spine; this psychic energy then winds its way up through the chakras of the body until the yogi’s consciousness merges with Cosmic Consciousness or Brahman. Once inside the temple I unwrapped a seed pod and presented it to my sanyasi friend. He instantly identified it as Datura. When asked if he had ever tried smoking or eating the harmless looking seeds he shook his head in dismay, adding that the plant was highly poisonous. Three more yogis joined in our discussion. One of them who, perhaps not by coincidence, had a slightly crazed twinkle in his eyes, said that he had smoked several seeds in a chillum once in his life, on Maha Shivartri, the Night of Shiva. When I asked him about the effects he ruefully told me that he had gone mad for three days. This was why he never planned to repeat the experience. Finally I asked the group if they knew of any yogis with more experience of Datura intoxication to which they all agreed that the great Datura experts were the Aghori babas, one of whom was currently resident in Pashupatinath, Nepal’s most important Shiva temple.

The next step was to find individuals with firsthand knowledge of the effects of Datura. Theoretically these people could have been religious members of either Hindu or Buddhist traditions but since the Vajrayana Buddhist tradition is often willfully hidden from the purview of outsiders by those who practise it, I thought it wisest to make inquiries amongst the yogis of the Kal Mochan temple in Thapthali, one of whom I was on relatively good terms with at the time. It is well known that yogis smoke psychoactive plants in order to awaken the shakti of the Kundalini Snake which otherwise remains coiled at the base of the spine; this psychic energy then winds its way up through the chakras of the body until the yogi’s consciousness merges with Cosmic Consciousness or Brahman. Once inside the temple I unwrapped a seed pod and presented it to my sanyasi friend. He instantly identified it as Datura. When asked if he had ever tried smoking or eating the harmless looking seeds he shook his head in dismay, adding that the plant was highly poisonous. Three more yogis joined in our discussion. One of them who, perhaps not by coincidence, had a slightly crazed twinkle in his eyes, said that he had smoked several seeds in a chillum once in his life, on Maha Shivartri, the Night of Shiva. When I asked him about the effects he ruefully told me that he had gone mad for three days. This was why he never planned to repeat the experience. Finally I asked the group if they knew of any yogis with more experience of Datura intoxication to which they all agreed that the great Datura experts were the Aghori babas, one of whom was currently resident in Pashupatinath, Nepal’s most important Shiva temple.

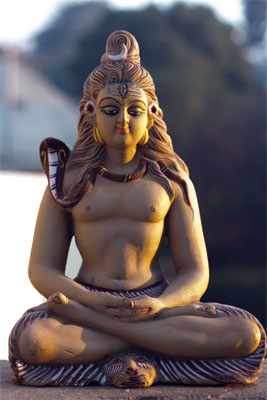

I felt that I was edging closer to the heart of the Datura mystery. It made sense to me that Aghori babas would be the most knowledgeable about Datura since the Aghori are a Shaivite sect and Datura is explicitly linked to Shiva in the Hindu scriptures. For example, according to the Vamana Purana, Datura grew from the chest of Lord Shiva, while in the Garuda Purana, it is said that Datura flowers were offered to the god Yogashwara (Shiva) on the thirteenth day of the waxing moon in January. I wondered if the yogi at Kal Mochan had exaggerated the length of his Datura intoxication for my benefit but further research into the effects of ingested Datura made his claim entirely plausible. Scopolamine is technically not classed as a psychedelic but as an anticholinergic delirient. A list of effects include, “a complete inability to differentiate reality from fantasy; hyperthermia; tachycardia (raised heartbeat) bizarre, and possibly violent behavior; severe mydriasis (pupil dilation) with resultant painful photophobia (intolerance to light) that can last several days and pronounced amnesia.” The mental state brought about by Datura outlasts all other experiences caused by ingesting psychoactive plants. Timothy Leary, the controversial academic hippie advocate of psychedelic drug use in1960s and 70s America is alleged to have said that he had never heard of such a thing as an enjoyable scopolamine experience. Why then, it might reasonably be asked, would anyone repeatedly smoke the seeds of the Datura? And the answer, I suppose, is that like any potent mind altering substance, Datura has the power to transport the mind into other worlds which, while potentially terrifying, are also potentially divine. However, Datura seems to conjure its magic in a particularly fierce, unforgiving and dangerous way.

I felt that I was edging closer to the heart of the Datura mystery. It made sense to me that Aghori babas would be the most knowledgeable about Datura since the Aghori are a Shaivite sect and Datura is explicitly linked to Shiva in the Hindu scriptures. For example, according to the Vamana Purana, Datura grew from the chest of Lord Shiva, while in the Garuda Purana, it is said that Datura flowers were offered to the god Yogashwara (Shiva) on the thirteenth day of the waxing moon in January. I wondered if the yogi at Kal Mochan had exaggerated the length of his Datura intoxication for my benefit but further research into the effects of ingested Datura made his claim entirely plausible. Scopolamine is technically not classed as a psychedelic but as an anticholinergic delirient. A list of effects include, “a complete inability to differentiate reality from fantasy; hyperthermia; tachycardia (raised heartbeat) bizarre, and possibly violent behavior; severe mydriasis (pupil dilation) with resultant painful photophobia (intolerance to light) that can last several days and pronounced amnesia.” The mental state brought about by Datura outlasts all other experiences caused by ingesting psychoactive plants. Timothy Leary, the controversial academic hippie advocate of psychedelic drug use in1960s and 70s America is alleged to have said that he had never heard of such a thing as an enjoyable scopolamine experience. Why then, it might reasonably be asked, would anyone repeatedly smoke the seeds of the Datura? And the answer, I suppose, is that like any potent mind altering substance, Datura has the power to transport the mind into other worlds which, while potentially terrifying, are also potentially divine. However, Datura seems to conjure its magic in a particularly fierce, unforgiving and dangerous way.

The resident Aghori baba of Pashupatinath temple lives in a small room on the north side of the Bagmati opposite Bhasmeshvar ghat. As I enter he is sat crossed legged on his bed, smoking a chillum. Huddled on the floor are a group of youths, at least two of them busy packing chillums. Adorning the walls of the cell are two human skulls, one with a half smoked cigarette lodged between its jaws. The effect is grotesquely comic and also a little voodoo. The Aghori, a small bearded man of 75 years dressed entirely in black, smiles at me and welcomes my questions. I show him two seed pods, one Datura stramonium and one Datura metel which I have purchased from a stall outside the temple that sells votive offerings to Shiva devotees.

When I ask him which type, if any, he smokes, he interestingly picks out the Datura stramonium. Next I ask him how many times he has used the seeds. He ponders this a moment and then replies with total nonchalance, more than one thousand times. His reply is so different to every other yogi’s response so far that I wonder if he’s joking, but he looks entirely serious. I reflect that if anyone has willingly dosed themselves with Datura that many times then a member of a sect rumoured to indulge in necro-cannibalism and other taboo busting practices is about as likely a candidate as I’m going to come across. The Aghori then shares with me a recipe which he says removes some of the poison from the seeds – he prefers to cook them in ghee before eating them rather than smoking them. He then issues me with a firm warning: eating the seeds turns you into ‘half a man’ for many days. Finally, the old man leans forward and draws a black line across my forehead. It is a masan tika, made from the ash of a cremated human corpse. Somehow it seems like a fitting end, a line under my search for Shiva’s chest hair. n