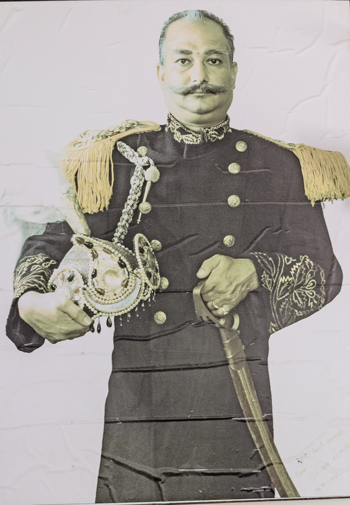

For many years after the advent of television in Nepal, Nepalis throughout the country were regaled with the highly entertaining, yet socially meaningful, dramas produced, directed, and acted in by an actor whose versatility knew no bounds.

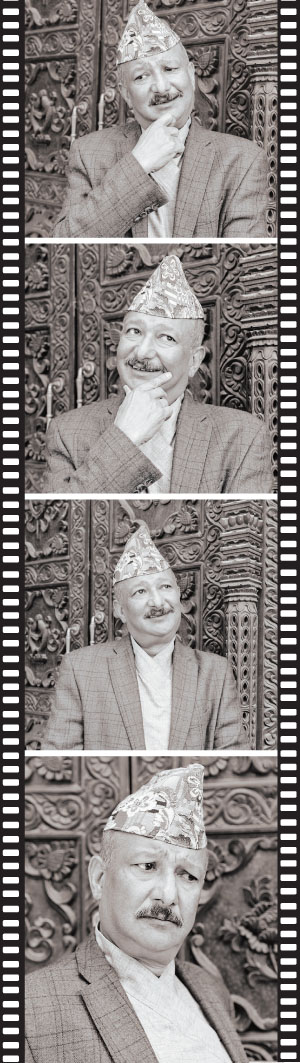

Based on our talk over the phone, I showed up at Santosh Pant’s neighborhood at precisely 9 a.m. on a Saturday morning, and waited for a few minutes in front of a red-brick house, Santosh ji’s home, located in a quiet, residential locality of Dhapasi Heights. Next to the house, two women were bent over a patch of vegetable garden, most likely domestic helpers collecting ingredients for lunch. The garden extended further; flowering plants swayed in neat, well-maintained spots. Two small dogs yelped and circled around me, as I took note of this calm, beautiful setting.

Based on our talk over the phone, I showed up at Santosh Pant’s neighborhood at precisely 9 a.m. on a Saturday morning, and waited for a few minutes in front of a red-brick house, Santosh ji’s home, located in a quiet, residential locality of Dhapasi Heights. Next to the house, two women were bent over a patch of vegetable garden, most likely domestic helpers collecting ingredients for lunch. The garden extended further; flowering plants swayed in neat, well-maintained spots. Two small dogs yelped and circled around me, as I took note of this calm, beautiful setting.

A minute or two after my presence was noticed by one of the helpers, Santosh ji peeked out from an upstairs window, and after exchanging a few words with me, swiftly came downstairs and opened the front door. I followed him to the living room near the entrance. It was a typical middle-class Kathmandu setting, bright curtains hung over a sofa set. Framed photos of Santosh ji and his family members adorned the walls. Numerous certificates were displayed inside a wooden closet with sliding glass doors. Photos and certificates also lined a curving stairway that snaked upwards from the other side of the living room.

After a brief introduction, I thanked Santosh ji for his time. When I asked him about his childhood, he retorted, “Why does every interview start with the same basic questions?”, so I promptly changed gears to Hijo Aaja ko Kura, his claim to fame. “When it first aired on Nepal Television, I had named the show Aaja Bholi ko Kura,” he began. “That was around 1995. It used to be a fortnightly show back then. That same year, I was invited to the palace at Sharada sarkar’s residence, along with a few other artists.” The royal family had gathered for their regular dinner, and the artists were seated in an adjoining room. At one point during the evening, King Birendra spoke to him, in English, “Why don’t you run this show on a weekly basis?” Promptly turning to Nir Shah, he ordered, “Can you make the necessary arrangements?”

After a brief introduction, I thanked Santosh ji for his time. When I asked him about his childhood, he retorted, “Why does every interview start with the same basic questions?”, so I promptly changed gears to Hijo Aaja ko Kura, his claim to fame. “When it first aired on Nepal Television, I had named the show Aaja Bholi ko Kura,” he began. “That was around 1995. It used to be a fortnightly show back then. That same year, I was invited to the palace at Sharada sarkar’s residence, along with a few other artists.” The royal family had gathered for their regular dinner, and the artists were seated in an adjoining room. At one point during the evening, King Birendra spoke to him, in English, “Why don’t you run this show on a weekly basis?” Promptly turning to Nir Shah, he ordered, “Can you make the necessary arrangements?”

On hearing this, Santosh ji was a bit worried at first. He was used to a two-week timeline to produce an episode. At a meager fixed remuneration of Rs.20,000 per episode (it went up to Rs.80,000 after a few years), he was responsible for the story, direction, and production, which meant recruiting supporting actors, scheduling shoots, and arranging meals. NTV provided the equipments and technicians. Following the monarch’s wish, he started a weekly production, and changed the name of the show.

Hijo Aaja ko Kura will no doubt be regarded as one of the most popular television shows in the history of Nepali television. It ran regularly for almost a dozen years on Nepal Television, with a total of 565 episodes. (The show also had a two-year run in Kantipur Television later.) “I think the reason for its success was because I was able to connect with the largely middle-class television-viewing audience. Since I also consider myself middle-class, I created stories based on what I knew, stories about everyday problems that we all faced,” he explained. Another reason why the show had such a massive impact was that he was able to convey social messages in a clever, satirical, and humorous way.

“I think that artistic entertainment should always have some kind of purpose,” he declared. “What’s the use of making a fool of oneself in front of a camera if the only point is laughter? And, why would anyone follow an actor if the actor doesn’t have valuable messages?” To stretch that idea, I pushed him with “That means you consider yourself to be an artist with a vibrant social consciousness?” “Yes,” he replied. “I consider myself to be a born artist. I never received any formal training in this field. And my work is often focused on socio-political issues.”

On that note, our conversation inevitably veered towards politics. “Look,” he turned towards me with a grave expression, “I’m not saying democracy is bad. Democracy is like a truck carrying valuable resources. To take the resources from one point to another, there needs to be cooperation. Cooperation to load the truck and clear the way. Finally, an able person who is widely trusted needs to drive the truck from point A to point B. In our case, we haven’t had a driver like that. As a result, the resources are not getting to places where they are most needed.”

On that note, our conversation inevitably veered towards politics. “Look,” he turned towards me with a grave expression, “I’m not saying democracy is bad. Democracy is like a truck carrying valuable resources. To take the resources from one point to another, there needs to be cooperation. Cooperation to load the truck and clear the way. Finally, an able person who is widely trusted needs to drive the truck from point A to point B. In our case, we haven’t had a driver like that. As a result, the resources are not getting to places where they are most needed.”

“There hasn’t been any leader in Nepal who is as visionary and committed to the country as King Mahendra,” the actor continued. “I will not hesitate to say that the country was better off during the monarchy. As soon as King Gyanendra realized that a lot of lives were at stake, he gave the country back to the people. He could have wiped out thousands of lives if he had wanted to. And Prachanda? He killed some 17,000 people, and rose on their blood without any remorse.”

“There hasn’t been any leader in Nepal who is as visionary and committed to the country as King Mahendra,” the actor continued. “I will not hesitate to say that the country was better off during the monarchy. As soon as King Gyanendra realized that a lot of lives were at stake, he gave the country back to the people. He could have wiped out thousands of lives if he had wanted to. And Prachanda? He killed some 17,000 people, and rose on their blood without any remorse.”

“But, Santosh ji,” I tried to reason with him, “King Mahendra and his politics is generally criticized because he suppressed multiple voices and pushed a national agenda that benefitted selective groups and excluded others…”

“How can you say that?” he questioned. “When King Mahendra noticed the plight of the Manang people, he provided tax-free business opportunities for them. During his reign, Hiralal Bishwakarma and a couple of other Janajati leaders became ministers. He brought people from the pahad to the terai, so that they could assimilate more smoothly with each other, and there wouldn’t be ethnic divide in the future.”

“But it’s precisely because of this move that there is such historical grievance, about the way a lot of pahadis were granted land that belonged to native Tharus of the terai…”

“That’s not true. He granted land that belonged to the government. In any case, King Mahendra also made moves to open border access to China, so that the country wouldn’t have to depend on India alone. How can you compare all that to the crop of politicians who have been trying to run the country after multi-party democracy entered the scene?”

“That’s not true. He granted land that belonged to the government. In any case, King Mahendra also made moves to open border access to China, so that the country wouldn’t have to depend on India alone. How can you compare all that to the crop of politicians who have been trying to run the country after multi-party democracy entered the scene?”

His political stance is understandable, because his work has been directly affected by the country’s instability. He largely blames the load-shedding routine for disrupting his success. “When there is no reliable electricity, one can’t count on a loyal audience. It was easier when we first started, because everyone could count on Friday nights. Now, there is no certainty. As a result, I don’t get the same support from the TV channels. Besides, it’s all about money and the market now. Whoever can pay the channels get the desired time-slots. These people also largely produce and dictate the content. And, there is no guarantee that they are the most qualified or talented.”

It is important to remember that Santosh ji was born into a comfortable Kathmandu family in Naya Bazaar. He entered Lab School when he was three, but since his father was a chief district officer who got frequent transfers, the young Pant attended school in various parts of Nepal along with his siblings (he is the fourth child among five). Although a government official, his father was inclined towards arts and literature. But, it was an uncle and his eldest brother who were the biggest sources of encouragement when it came to developing the actor’s inherent talent.

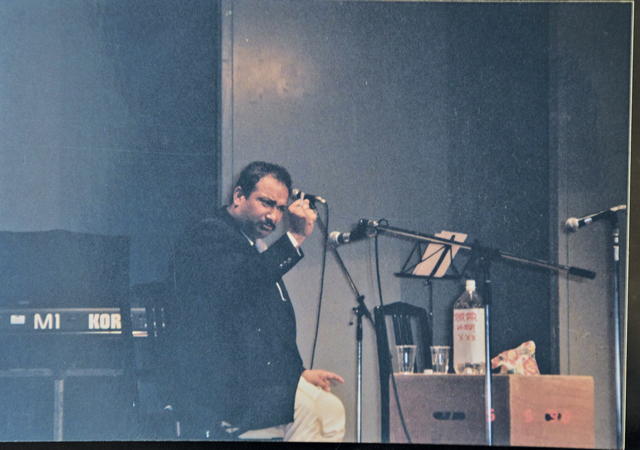

It wouldn’t be a stretch to say that Santosh Pant had an ideal home environment that nurtured him, and set the stage for his fame. Soon after high school, starting in 1975, he began performing in the annual Gai Jatra live shows, along with other comedians like Bhim Nidhi Tiwari and Harihar Sharma. “For 10 years straight, I received the top Gai Jatra awards, and gradually became well-known. When Nepal Television launched in 1985, Nir Shah provided a platform for me to expand on the work I was already involved in.” He produced and acted in a couple of other NTV shows before Hijo Aaja ko Kura.

When I got curious about his experiences with the mainstream Nepali film industry, he strongly stated his preference for television. “Most movies made back then were imitations of C grade Bollywood films. Besides, I was quite busy for a few years, and did not have much time. But, in recent years, there has been a surge of new energy in the film industry, with some earnest efforts.” When I asked him to offer some names, he mentioned that he liked Nir Shah’s Seto Baagh, along with some others’ movies, such as Nai Nabhannu La and Wada Number Chha.

“I don’t like the intense schedule and the night shifts that these film people stick to,” he also said. “That’s the Bombaiya way. They bring in technicians from Bombay who are used to this kind of lifestyle, but it’s different in Nepal. I wake up early and eat daal bhaat at ten, so I can’t do that.”

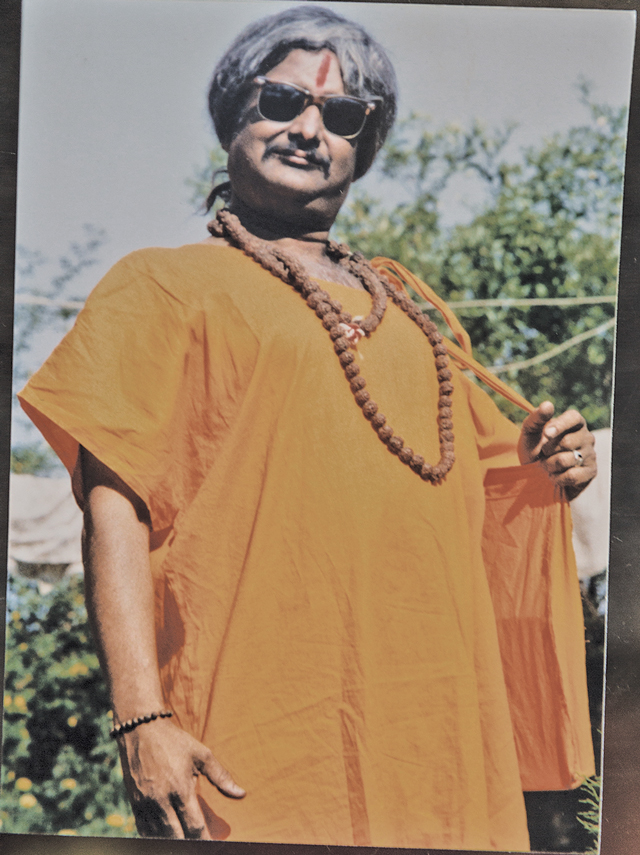

During his busiest phase, Santosh ji stuck to a strict schedule. He would shoot on Mondays, Tuesdays, and Wednesdays, edit on Thursday, and take the weekend off. “I liked going to Sauraha on Friday, and returned on Saturday. On Sunday, I worked on the upcoming story.” That is another noteworthy thing about the famous actor, which he made a point to emphasize. “I helped boost domestic tourism. Back then, very few Nepalis went to Sauraha, but since I was attached to the place, I based a couple of episodes there. Even then, tourism didn’t pick up. So I got an idea one day—children. I showed kids riding on elephants and boats. As you know, once kids are into something, it’s easy to get the parents on board. After that, domestic tourism in Sauraha rose sharply.” Santosh ji is also a vice president of the Nepal Rafting and Canoeing Association.

During his busiest phase, Santosh ji stuck to a strict schedule. He would shoot on Mondays, Tuesdays, and Wednesdays, edit on Thursday, and take the weekend off. “I liked going to Sauraha on Friday, and returned on Saturday. On Sunday, I worked on the upcoming story.” That is another noteworthy thing about the famous actor, which he made a point to emphasize. “I helped boost domestic tourism. Back then, very few Nepalis went to Sauraha, but since I was attached to the place, I based a couple of episodes there. Even then, tourism didn’t pick up. So I got an idea one day—children. I showed kids riding on elephants and boats. As you know, once kids are into something, it’s easy to get the parents on board. After that, domestic tourism in Sauraha rose sharply.” Santosh ji is also a vice president of the Nepal Rafting and Canoeing Association.

So, what next? He is interested in producing a reality TV show along the lines of Crime Patrol and Sawadhan India that he watches regularly. Just like Hijo Aaja ko Kura, he wants to be involved in a project that is socially relevant and can help the public in some way. He has already pitched the idea to some channels, and is waiting to hear from them. He also appears on the big screen now and then, and spends some of his valuable time guiding and working with his son who is managing Pant Film Productions. The production company launched a YouTube series, Hospital, in 2013, a reality TV show that aims to provide relevant information to the public. Apart from the son and one daughter at home, he has another daughter who lives in the United States.

I felt honored to meet the famous actor and converse with him. The interview went smoothly, and lasted for about 90 minutes. Mrs. Pant walked across the room a couple of times on her way back and forth from the upstairs landing. At one point, she paused and inquired whether I wanted tea. I didn’t. I had asked for a glass of water at the beginning of the interview, which she had been brought to me earlier, along with a glass of lemon water for the famous actor.