A glimpse into the history of Nepal’s eldest newspaper

It is difficult, for many of us, to imagine a life without computers, mobile phones or tablet devices, these little virtual windows to a reality that is not physically present before our eyes. Go a hundred years back in time and you will get to a Nepal where people were doing perfectly fine without cell phones or the internet, or for that matter, the TV or even electricity. News came in the manner of rumors and gossips in the neighborhood junctions. People perhaps went to dhunge dharas, chautaris and patis in the evenings to get a daily dose of their newsfeeds which these days we can get on our cell phones with a flick of a fingertip. Mass communication was done through traditional techniques like ‘Katuwal Karaune,’ ‘Jyali Pitne’ and ‘Shankha Phukne’. It was during those darker and quieter times that the first printing press rattled at a corner of Thahiti, Kathmandu and for the first time brought voices from people living far away, much farther than just the next neighborhood or the next village.

The Back Story

The Back Story

My quest for the story behind the origins of this time-honored newspaper began from the book Nepal ko Chapakhana ra Patrakarita ko Itihaas, considered one of the first and finest books on the history of media and journalism in Nepal. The author Grishma Bahadur Devkota often punctuates the barren academic tone of the book with interesting anecdotes and original excerpts from many documents that partook in the birth of Gorkhapatra, documents now long lost and mostly forgotten. As I leafed through the chapter on the history of Gorkhapatra, it began to dawn on me that the terrible period in the history of Nepal when the country was under the iron soles of the Rana regime might not have been as terrible as I had thought.

We generally view the 104 years of Rana rule as among the dark eras in the history of Nepal, since the country, its people and its resources were all severely exploited to serve the extravagant needs of a few elite. Rana oligarchs didn’t let education reach the general public and denied them the freedom of expression or information. Yet not all those who came to power were inconsiderate, self-serving tyrants, and certainly not all of their deeds, regardless of their intentions, have been detrimental to the nation. The story of Gorkhapatra, and with it the history of print media in Nepal ironically begins with the rise of Junga Bahaur Rana as he set out to establish a dictatorship that shrouded the country for over a century.

Once Junga Bahadur had eliminated his major rivals in the royal court ensuring his ascension to the post of the prime minister, he took a trip to Britain leaving from Calcutta in April 1850 and returning to Kathmandu in February 1851. He returned with several ideas for modernization and policies to strengthen ties with the Great Britain. Among many things that Junga Bahadur imported from his trip besides European architecture, fashion and furnishing was a printing press. This hand press that had an Eagle trademark on it was called Giddhe Press, and was first used to print the 1400 page Muluki Ain, an early attempt to codify laws for the nation, in 1854. The printing press was kept at the Prime Minister’s Palace at Thapathali, Kathmandu and mostly remained dormant for about half a century until it was dusted off to print Nepal’s first newspaper in 1901 AD.

Once Junga Bahadur had eliminated his major rivals in the royal court ensuring his ascension to the post of the prime minister, he took a trip to Britain leaving from Calcutta in April 1850 and returning to Kathmandu in February 1851. He returned with several ideas for modernization and policies to strengthen ties with the Great Britain. Among many things that Junga Bahadur imported from his trip besides European architecture, fashion and furnishing was a printing press. This hand press that had an Eagle trademark on it was called Giddhe Press, and was first used to print the 1400 page Muluki Ain, an early attempt to codify laws for the nation, in 1854. The printing press was kept at the Prime Minister’s Palace at Thapathali, Kathmandu and mostly remained dormant for about half a century until it was dusted off to print Nepal’s first newspaper in 1901 AD.

Two print publications in Nepali language already existed during that time. ‘Bharat Gorkha Jeevan’ was the first Nepali magazine published monthly from Banares, and ‘Sudhasagar’ was another Nepali Literary magazine published from Kathmandu. But both publications did not survive for long due to the lack of financial resources, infrastructure and support from the government.

Two print publications in Nepali language already existed during that time. ‘Bharat Gorkha Jeevan’ was the first Nepali magazine published monthly from Banares, and ‘Sudhasagar’ was another Nepali Literary magazine published from Kathmandu. But both publications did not survive for long due to the lack of financial resources, infrastructure and support from the government.

Dev Shumsher Rana was the most liberal and reformist of the Rana Prime Ministers, and it was under his initiative that the Nepali people got their first taste of print journalism. As one of his reformative enterprises, he handed over the Giddhe Press also known as the Type Press, and a Lithograph Press to Pandit Naradev Pandey, the former editor of ‘Sudhasagar’, and authorized him to publish ‘Gorkhapatra,’ a newspaper from the land of Gorkhalis. With full support from the Prime Minister, it became the first newspaper to be published in Nepal.

The Birth of an Era?

The Birth of an Era?

Gorkhapatra was a golden beginning for print journalism and mass media in Nepal. A modern equivalent would be the advent of the Internet in the 90’s. During the time of its publication, it was among the few newspapers that were being published in the whole of South Asia in local languages. It began as a weekly newspaper and remained so for the next four decades. The first issue was eight pages long, which celebrated this advent in the field of mass communication through poetry and prose. The editorial called ‘Editor ko rai’ explained the importance and purpose of Gorkhapatra for its readers with the central message: ‘Information is knowledge’. It claimed that the newspaper would serve the public by disseminating news, information, education and inspiration acting as a bridge between the ruler and the people.

While information is knowledge, it also empowers. Rana rulers did not want to weaken their hold over the country, but an increase in awareness and education among the people could pose a threat to the regime, so the paper was subjected to strict supervision by the authorities. A royal decree called ‘Sanad’ was in place which had the guidelines for what could and could not be published in Gorkhapatra. Before any material was printed, it was sent for a final review by Lieutenant Colonel Dilli Shumsher Thapa Chettri before being published.

Nonetheless, if we take a look at the Sanad issued by Dev Shumsher, it shows how progressive and far ahead of his contemporaries Dev Shumsher really was. The entire document is reproduced in Devkota’s book. One of the lines in the document says that any unjust decisions made in courtrooms can be reported in the newspaper. The next one adds if any government official is found to be showing neglect in his duties or is absent from his office during office hours, such situation shall also be reported in the newspaper. Another one says “any reports of injustice or violence in the hills or terai should be published without any charge to the reporter.” Under the heading “What not to publish” was also this: “Don’t publish our [the Prime Minister’s] praise and plaudits.” These show that despite the dictatorial powers held by Dev Shumsher, the man was a true reformist with modern visions for the nation. It should not be so surprising then, that he was the prime minister who attempted to introduce a parliamentary system in the country way before it finally came into practice more than half a century later.

Nonetheless, if we take a look at the Sanad issued by Dev Shumsher, it shows how progressive and far ahead of his contemporaries Dev Shumsher really was. The entire document is reproduced in Devkota’s book. One of the lines in the document says that any unjust decisions made in courtrooms can be reported in the newspaper. The next one adds if any government official is found to be showing neglect in his duties or is absent from his office during office hours, such situation shall also be reported in the newspaper. Another one says “any reports of injustice or violence in the hills or terai should be published without any charge to the reporter.” Under the heading “What not to publish” was also this: “Don’t publish our [the Prime Minister’s] praise and plaudits.” These show that despite the dictatorial powers held by Dev Shumsher, the man was a true reformist with modern visions for the nation. It should not be so surprising then, that he was the prime minister who attempted to introduce a parliamentary system in the country way before it finally came into practice more than half a century later.

‘Gorkhapatra’ was founded with the view to drive the nation forward by revolutionizing communication and media. The founders of the newspaper were aware of the importance of newspapers for a country’s development. A long list containing fourteen points on advantages of having a newspaper was published on the second page of the first issue. While the list was meant to promote the paper among the public, it also demonstrates the promises the paper carried for its founders. It was a birth of a new era in mass com munication. The readers were going to be able to have their news on local, national and international affairs, market prices of goods, exchange rates and much information for which they had to pay high prices before delivered right to their hands for a mere 4 rupees a year. The paper was also going to serve as a medium for the public to express their problems and grievances to the government. Like a lamp lit in a cave, it was going to slowly eliminate the darkness of illiteracy and ignorance.

munication. The readers were going to be able to have their news on local, national and international affairs, market prices of goods, exchange rates and much information for which they had to pay high prices before delivered right to their hands for a mere 4 rupees a year. The paper was also going to serve as a medium for the public to express their problems and grievances to the government. Like a lamp lit in a cave, it was going to slowly eliminate the darkness of illiteracy and ignorance.

Crumpled Hopes

Individuals with progressive ideas and motives like Dev Shumsher were a rarity during his time. His reforms were not being held in a positive light by his associates in the palace. Gorkhapatra’s early awakenings could not last while the palace was dominated by the hidebound factions of Rana aristocracy. Less than two months after the publication of the first issue of Gorkhapatra, Dev Shumsher was deposed from the post of the prime minister and replaced by the hardliner Chandra Shumsher. Many liberal policies introduced by Dev Shumsher were suspended by the new prime minister who saw those policies as a threat to the Rana Regime.

Gorkhapatra was lucky to survive but it wasn’t allowed to grow. Harsher rules were put into effect to limit media activities. The number of copies of the newspaper printed per issue was brought down to 200 from 1000. While even Gorkhapatra was under a constant threat of being shut down, it was the only wide-print publication in Nepal to make it through the 31 years of Chandra Shumsher’s iron-fist rule.

During the Rana years, Gorkhapatra had to struggle to maintain its readership. While the literate population itself was a tiny minority, even among them the newspaper was not so popular because of the tight government control over its contents. The newspaper functioned as a mouth piece of the government. Other contents were subjected to heavy censorship. Local and national news came from government offices, and there were no ‘news reporters’ designated by the paper. International news were translated from foreign newspapers. Due to this, the newspaper contents tended to be stale and unappealing to the readers.

Gorkhapatra Archives

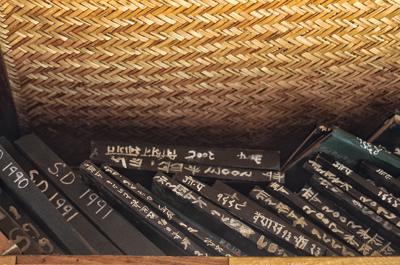

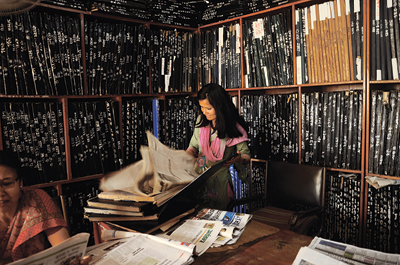

Only one copy of the first issue of Gorkhapatra survives till this day, preserved at the Madan Puraskar Library in Patan Dhoka. Because the library was undergoing internal changes I could not get access to the paper. So I went to Gorkhapatra Sansthan to see if I could lay my hands on any early issues of the newspaper. And voila, there in the archives on the top floor of the building were shelves filled with oversize folders containing old issues of Gorkhapatra.

These issues were dated as early as 1958 BS (1901) the first year of its publication. Slightly smaller than the broadsheet dailies we get today, these more than a hundred years old papers were of a yellowish, off-white color with a thin layer of dust. The 8-page papers were torn at places and filled with columns of text from top to bottom and left to right with barely readable font. Except on the front page where above the name ‘Gorkhapatra’ is an imprint of the goddess Sawaswoti holding her veena, these issues contain no pictures.

Unlike in modern papers, the contents of the early papers were not clearly categorized and organized in a particular sequence. They look like exceptionally long articles extending over multiple columns and pages.

Sections containing moral, spiritual, practical and health related messages appear regularly in the early issues, an equivalent of lifestyle and health sections in today’s periodicals. National news under the section “Deshko Khabar” has accounts of activities of the prime minister or the king, mostly about their official visits to distant villages and public acts of community service. The issues in the month of Baisakh also have a series of reports about marriages and other family celebrations held within the circle of Rana aristocracy. The international news were mostly about wars happening around the world without much commentary. The weather section reported the weather conditions in various places in the country as observed during the previous week.

Sections containing moral, spiritual, practical and health related messages appear regularly in the early issues, an equivalent of lifestyle and health sections in today’s periodicals. National news under the section “Deshko Khabar” has accounts of activities of the prime minister or the king, mostly about their official visits to distant villages and public acts of community service. The issues in the month of Baisakh also have a series of reports about marriages and other family celebrations held within the circle of Rana aristocracy. The international news were mostly about wars happening around the world without much commentary. The weather section reported the weather conditions in various places in the country as observed during the previous week.

Gorkhapatra played an important role in providing the platform for a literary awakening during the dark years of Rana regime. Before that literature especially poetry was limited to small academic and elite circles, while the rest were confined to oral traditions. Until the literary monthly Sharada began its publication in 1935, Gorkhapatra provided the much-needed forum for the publication of poems, stories and articles. Serialized fiction and pieces of proto-types of modern short stories can be found through out the early issues of Gorkhapatra. During late 80’s and 90’s, many distinguished poets of Nepali literature most notably Siddhicharan Shrestha and Gopal Prasad Rimal launched their literary career by publishing their poems in Gorkhapatra. Rimal’s poem titled Kavi ko Gaan or “Poet’s Song” which was acclaimed as the first Nepali poem in free verse made its first appearance in Gorkhapatra in 1935.

Gorkhapatra with its very unlikely beginning and decades long history under suppression remained the leading news publication in Nepal through the first half of the 20th century. It was the chronicler of Nepal’s modern and early modern history, and the precursor to the information age that we are relish today with hundreds of dailies in print and minutely updates through millions of news sources online. For many of our elders, the word ‘gorkhapatra’ is still synonymous with a newspaper. But it wasn’t just a newspaper. It was a telescope with views of the world beyond the towering hills, a venue for young graduates to announce their talents, an avenue that brought early peeps of literary awakenings to public ears, and probably the only guiding light for the general public towards literacy.

Rising from the Ashes

Rising from the Ashes

Change often comes not as a breeze but as a storm. History is witness. The late 70s were tempestuous years in the kingdom of Nepal, for the king as well as the people. Those times were filled with events that culminated in a referendum on May 2, 1980. They were the years of protests with anger in the air, and hopes and fears under the breaths of those who were fighting for change.

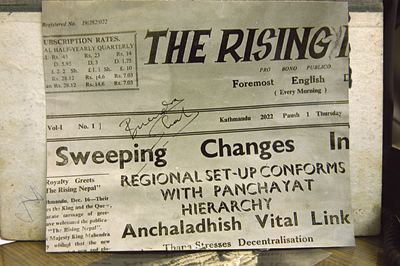

On the evening of May 24 1979, King Birendra made a historic announcement on Radio Nepal. Through a referendum, people would be allowed to decide the nature of their government: either a reformed Panchayat system or a multi-party democracy. The previous night, Gorkhapatra Sansthan was literally on fire. Papers were reduced to ashes and the printing equipment sustained severe damages and were in no condition to print. Yet, there was a government directive to the editors to publish both dailies, Gorkhapatra and The Rising Nepal in order to deliver the significance of the announcement to the nation.

“ We were summoned to Singha Durbar on that day,” recalls Mana Rajan Josse, who was the Editor-in-Chief of The Rising Nepal at the time, “and told to prepare editorials for the next day’s issues.” The proclamation meant critical changes in the political climate of the country. Two clear pathways were now open to the people. An absolute monarchy in the name of Panchayat wasn’t the only option any more; the power in the figure of the monarch had now diminished. It was a dawn of political freedom. “His Majesty and His Majesty’s Government were no longer the same thing.” says Mr. Josse, “So I wrote the editorial keeping this in mind that two possibilities existed and as a newspaper we had to be fair to the both sides.”

We were summoned to Singha Durbar on that day,” recalls Mana Rajan Josse, who was the Editor-in-Chief of The Rising Nepal at the time, “and told to prepare editorials for the next day’s issues.” The proclamation meant critical changes in the political climate of the country. Two clear pathways were now open to the people. An absolute monarchy in the name of Panchayat wasn’t the only option any more; the power in the figure of the monarch had now diminished. It was a dawn of political freedom. “His Majesty and His Majesty’s Government were no longer the same thing.” says Mr. Josse, “So I wrote the editorial keeping this in mind that two possibilities existed and as a newspaper we had to be fair to the both sides.”

Small pocket size newspapers were published in the name of The Rising Nepal and Gorkhapatra from the government press at Singha Durbar the next day. But they signified big changes in the course these newspapers would take in the following years. Although the publications were under the government’s jurisdiction, according to Mr. Josse, he and his team worked hard to be increasingly fair over a period of time. “After 8 or 10 days, the printing machines at Gorkhapatra Sansthan were restored, so we reverted to our old work place but with new mind set,” Josse recalls, “Preparations for the referendum were on full swing.

Political campaigns by parties for and against the Panchayat were being held all across the country. Our major concern was to cover both campaigns equally.”

Mana Ranjan Josse joined the first editorial team of The Rising Nepal in 1965 with barely any professional training in journalism but with solid academic background in International Relations. Josse later became the Editor-in-chief of The Rising Nepal and led the editorial for several years during the Panchayat Era. He recalls his time in Rising Nepal with a bit of pride and a bit of nostalgia. “Although the government did try to interfere with our work at Rising Nepal, we did our best to work our way around to deliver impartial news to the public,” he says.

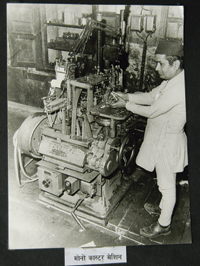

During his time, the publication used lithograph press which was tedious, time consuming and very prone to typos. Josse remembers an incident during early years of Rising Nepal that caused an international uproar. The paper had mistakenly published “late Zakir Hussain” in a news about the then Indian President Dr. Zakir Hussain’s visit to Nepal. Indian presses exploded with criticism directed at the newspaper and the Nepali government until the president himself took notice and dismissed it as an accidental blunder.

After the referendum, The Rising Nepal was recognized by the US State Department for its impartial coverage of news while the country was preparing for the referendum. But Josse most vividly and joyfully recalls a conversation he had with BP Koirala during his visit to India: “I asked him what he thought of the coverage during the referendum era, and he replied right away, ‘You’ve been more than fair.’