Rijal traveled to five villages in search of the “phanderwanam” and “katwanam”, musical instruments many believed no longer existed. He had almost given up, when he met a guy at a tea shop in Haldibaari village in Jhapa district. The man took Rijal to the place he was so desperately looking for. There, he met the old man who was perhaps the last person to possess the knowledge of instruments lost to history.

In the 1950s, geologist Toni Hagen traversed thousands of kilometers across Nepal on foot documenting the beautiful Nepali culture and music. In the 1960s, it was Terence R Bech who came to Nepal as a volunteer and traveled from corner to corner carrying his tape recorder, recording traditional Nepali folk music, collecting musical instruments, and translating the native lyrics. Following in their footsteps, scholar-musician Dr. Lochan Rijal traveled to several districts, such as Bhojpur, Panchthar, Salyan, Dang, Kaski, and others for his field research. Rijal, who has a doctorate degree in ethnomusicology, has been on a quest to revive Nepali folk music and the musical instruments that have got lost in the continuum of history after modern influences distorted it.

Discovering the Magic of Music

Rijal was born in a remote village in Panchthar into a large family. His parents passed away when he was very young. He had three brothers and five sisters. His village had limited access to technology like television and the radio, so he grew up listening to folk and ritual music. He lived in Panchthar till he was nine years old, and then his siblings sent him to Biratnagar.

When he was in Panchthar, he heard a beautiful tune, a tune of a guitar. "It was A major chord" he recalls. He was fascinated by it and always wanted to buy it. The dream became a reality when he came to Biratnagar for schooling. He went to his friend Siddhartha to buy his uncle's guitar. It was an old guitar with a bent neck; he sold it to Rijal for 150 rupees and a few books. He was very lonely in Biratnagar; he had no parents or guardians, so his friends and music became his family. He became a self-taught guitarist when he was in the eighth grade. “I bought a book called 'Guitar Guide' written by Ram Thapa. I used to read it by hiding it inside the health science book whenever my brother was around, because he used to tell me to read my course books. I didn't follow any theories, but the book helped me to understand about chords.”

One day, a boy from his school discovered him playing the guitar and came up to him. Little did he know that the young boy had a band. He asked Rijal to join his band, and he accepted the offer without a second thought. “I played everything by instinct, by hearing the sound from instruments and organizing it in my head. They invited me to be a lead singer, but I started as a drummer. I began drumming by playing the Tama drums which were quite popular in those days. Sometimes I played the guitar, sometimes the drums, and other days, I used to sing.”

His teachers also had a great influence on him. He had some teachers who were from Darjeeling, India. “I remember sneaking into the playgrounds in the evening to watch them sing and play guitars. They provided me with guidance, as well.”

Taking the First Steps

Rijal enjoyed the process of converting his thoughts into words and then bringing those words to life by adding music to them. He started writing his own music and compositions, and wrote 8 to 10 songs at the time. But, it wasn't until the 10th standard that he really started making some serious music after he and his friends formed a small band called The Steps. “We were a young band. I was just 15, and I enjoyed the experience to the fullest. Our band traveled around with the little pocket money we had and felt like we had become rock stars.”

It was the time when the trend of forming a band was increasing among Nepali youth. He utilized the popular music trends of the time to record his first ever song in a studio in Dharan. “We headed to Dharan full of anticipation. The song was recorded in an old school four-track recorder, and the studio charged us only 800 rupees for the recording. I don't have the song with me right now. I have no idea where the audio is. It was a simple soft rock song about a love story. We thought it would be commercially successful, because romantic songs were trendy at the time.”

Rijal was gifted, but kept his talents hidden from his family. He buried the little treasure in the ground, to keep it safe. One day, his elder brother arrived while Rijal was playing the track in a tape recorder, and after hearing it, he asked Rijal about the song. He was surprised when Rijal told him that it was a song recorded by him and the band.

“He gave me the money when I told him about the cost. We still argue about this story, because he reminded me just yesterday that he gave me 900 rupees, not 800!”

Little did Rijal know that this secret talent could lead him on a career path and the road to success. Although he started as a drummer in a small band, he went on to record numerous songs. His songs even became chart toppers, especially songs from his album, Coma, which he recorded with Samjhana Audio Visual. The album won numerous national awards and topped many charts.

Changing Tracks

Rijal majored in science in Nepal Police School during his high school and prepared for the medical science examination, because he always wanted to be a medical doctor. But, fate had something else planned. Music left such a lasting impression on his life that he decided to join Kathmandu University to do his bachelors, and then masters, in ethnomusicology. He was absent from the music scene while pursuing his degree, and by the time he completed his research, he had become a completely new individual. His academic research had shaped his music in a way he had never anticipated. He wanted to learn more about folk music, he wanted to learn to play new instruments and compose songs using them. That was also the time when his love for the sarangi grew. Teaching music at the Nepal Music Center and Unique International School had instilled the desire in him to learn more about music, and he decided to pursue a doctorate degree in ethnomusicology. But, there was no provision to do PhD in music in Nepal, so he looked for scholarship opportunities abroad.

“I got a scholarship to the University of Massachusetts. My thesis was titled, ‘Transmission of Music in Nepal’, and it focused on the music education database in Nepal. It aimed to make a curriculum for music education and to contemporize endangered music traditions. I took the preparatory classes in the university and later enrolled in Kathmandu University. I collaborated with the university to do field research in several districts. I basically worked with Gandharva musicians. I did documentation, processing, analysis, and application model of the folk music in those districts and studied how it transmitted from one generation to another.’’

The Lure of the Local

He was attracted towards local instruments since his childhood. The sound of his sister Roja'smadal, a popular hand drum in Nepal, and the sounds of the shehnai, a tubular instrument played during marriages and processions, and narshima captured Rijal's imagination. But, it was when he came to Kathmandu University and met the head of department—German drummer, pianist and ethnomusicologist Dr. Gert-Matthias Wegner—that he really got into local instruments, Western classical music, and South Asian ‘ShastriyaSangeet.’ He also became very attracted to ethnic traditions like those of the Newars.

“I started playing various instruments like the dhime, the traditional drum of the Jyapus; the tabla, a membranophone percussion, classical guitars, and sarangi, a popular musical instrument in the western part of Nepal," said Rijal. In 2010, he started making arbajo, the male counterpart of sarangi, by collaborating with Hari Gandharba, a musician from Kaski. Arbajo has been very popular among Gandharva musicians since ancient times. They considered the sarangi a feminine instrument, since its sound was as compassionate as a woman, whereas an Arbajo was considered to be the male counterpart of the sarangi, since its tone and texture sound is lower in frequency. The arbajo is bigger in size and difficult to carry. “Arbajo was more rhythmic, while sarangi was more melodious. They used to be played together in the past,” he explained.

Folk music is the music of all the people of all the times, according to Rijal. For him, it's more like a language. “Folk music is used to narrate folklore, stories of a local community, the sadness and ecstasy. It is the music that preserves history by promoting culture and reflecting society. It is the national identity of our country.”

Winner of the best South Asian musician award in the South Asian Music Festival, he says that although he is a musician and not an activist, he believes the sound of musical instruments can raise awareness on various issues. “Music can be a very powerful tool to tell stories. ‘The Death of Emmett Till,’ a song by Bob Dylan, tells the story of events in 1955 when 14-year-old Emmett Till, an African American from Chicago, was murdered. “It’s amazing how Dylan used a song to tell a story on racial inequality present at the time.”

During the process of teaching and preparing the curriculum, Rijal realized the significance of Nepali musical heritage and its application. “I was very vocal about making music part of formal education. I even prepared the first draft curriculum and defended it when working with the government.” He realized that it could play a significant role in bringing different castes and ethnic groups together to contribute to the nation's development. Before television and radio arrived in the country, Nepali folk musicians were the newscasters for the country. To preserve and promote folk music, it should be part of the education. Kathmandu University has been bringing in local folk musicians into the faculty recently. The idea is to bring intangible knowledge to university academia. It also gives job opportunities to the singers, as well. “Musical instruments like naumatibaja, played by the Damaimusicans, needs to be integral in our education system.”

Enduring Sounds

Rijal gets introduced to musical instruments whenever he travels to new places. "I went to Korea to give a talk as a guest lecturer and also to perform in a concert. That is where I was introduced to traditional Korean musical instruments. I really liked the sound of the janggu, a slim waist drum that is the most popular drum in traditional Korean music, and started learning it. I am engrossed by all types of musical instruments. Understanding them gives me a lot of pleasure.” He feels life is meaningless if you don't discover and learn new things every day. On one occasion, when he went to Bangkok for a lecture, he carried some musical instruments with him just in case they wanted him to play. “There were instruments everywhere, from the gardens to the kitchen. The auditorium was so good that I didn't want to leave. I played the sarangi and everyone was in awe. They asked me if they could come to Nepal to play.”

Sound for Rijal is anything that alerts or triggers the human senses. He considers it an integral part of the universe. “Without sound, we wouldn't have ears.” Composing music comes naturally to him on some days. He fondly recalls a recent recording, where he had to play a flute although he doesn't consider himself a flute player. “I chose to play the murali, which is played like a trumpet, instead of the bansuri, which is a side-blown flute, and I was surprised how spontaneously I kept on playing it. But, when I base my composition in a concept or theme, it takes a lot of time for me.”

He sometimes prefers to work in isolation, in his room or veranda. But, he likes being with friends more, because he tends to overthink when he is in isolation, and he draws inspiration from people. “When I make music, I want to make music that can last one or more lifetimes,” he told me.

He has had several influences throughout his career: ‘Sawari Mero Railai Ma’ by Melava Devi has been a huge inspiration for him, since she is considered to be the first recording woman artist of Nepal. “I have listened to the music collected by Terence R. Bech at Madan Puraskar Pustakalaya (MPP) in Patan that mostly consists of the music of Karnali, which is something special. I have also watched the recordings of Toni Hagen, whose documentary had a lot of music. Ingemar Grandin and Dharma Raj Thapa are other individuals whose works have influenced me.”

Various Nepali musicians have inspired him, as well, and among them, Hari Maharjan stands out. “He has to be one of the best guitarists I know. He thinks guitar, doesn't just play it. I like Nabin Bhattarai a lot when it comes to pop music. He is like a brother to me.” Rijal has also been enthused by Nepathya and Kutumba, who have been promoting local instruments. “I have collaborated with them in many ways. I have had the opportunity to perform with Kutumba and write harmony score for Nepathaya, too. I get goose bumps when listening to musicians like Deepak Kharel, Deep Shrestha, Phatemaan Raj Bhandari, Tara Devi, Aruna Lama, Om Bikram Bista, Natikaji, and of course, Narayan Gopal.”

He also believes that singers don't need to have recordings, or have their songs played on the radio, to be great musicians. “The local musicians, who are self-taught, are world class musicians. The ones who inherit music, like Badi Gandharva from Salyan and the late Mohan Gandharva from Kaski, who used to sing songs on historic events such as Junga Bahadur Rana's visit to Britain or about the time when the Singha Durbar caught fire. The Santhals and the Limbu musicians have broken various barriers like caste, ethnicity, and politics to produce music worthy of awards like the Grammys.”

Although he likes performing live, he believes his music is bit more applied, or scientific, and prefers performing in front of a limited number of people, though he has enjoyed performing in front of large crowds in the past. “I remember a concert in Basantapur on climate change. It was the first time I played in front of a large crowd. There were other artists like Hari Maharjan, Mukti and Revival, and Jindabaad. My hands were shaking when playing the sarangi, because it was the first act of the concert. There was an old man staring at me, who I thought was a sarangi player, later I found out he was an instrument maker. The crowd later started cheering, which was a huge relief. After that concert, he and the other performers went to a restaurant for a jam session. His fellow musicians wanted him to sing, as well. He was on the guitar. “I don't know what happened to me, but it was like I was blessed with creativity. I went on a musical marathon, narrating freestyle stories like the Gandharva musicians, singing till the early hours of the morning.”

He feels that knowing one’s sound is the most difficult thing in music, and thinks teaching is a difficult job, since one has to be very subtle when doing so. But, it complements his work, because he says he learns from his students, too. Apart from teaching, he has also been involved with other work. The music department was affected by the recent earthquake, so he has been working closely with the university to get things back on track. The rebuilding of heritage sites in Tripureshwor is also taking his time. Implementing the project, co-coordinating with the architects, have been completely different experiences for Rijal. “I have to visit ministers, administrative officers, and senior civil servants of the Government of Nepal, which require a lot of patience.”

Inspiring Future

According to him, the way Kutumba has contemporized folk music has given hope that the future of folk music is bright. He has high hopes for his students; some of them have performed at the Soaltee Hotel, along with representatives of universities from around the world. Their performance was like a dream, according to Rijal. “One of my students, Sudhir, is such a wonderful tabala player that I requested him to play in a concert with me. He was very young at that time. He reminded me of my youth. We practiced for just 30 minutes before performing together. I enjoyed collaborating with him. Now, he is a drummer in the Night Band and plays in festivals all around the world.”

Recently, he has been busy with his new project titled,’ Nepali’. “I have written and composed the song and played seven instruments.” The aim is to showcase Santhal, Limbu, and Damai musicians. Musicians from Jhapa, Panchthar, Kathmandu, Terathum, Taplejung, and Dhading have come together for the song. Rijal had set out for a research on inclusion in Nepal. He took a mini studio with him to the field to record the music, and recorded visuals as well. “You can say I became a cinematographer for the first time. Neptunes Records helped me a lot, along with Leon Jervis.”

The intriguing thing is the use of the sitara/ektare, a rare Limbu instrument used in the song. Limbu musicians have used the instruments to sing Mundhum, their ancient folk literature. Damai singers have played narsimha in the song. The Damai musicians, without whom the royal ceremonies and traditional Nepali weddings weren't possible, have also played their music in the song.

“I have used a bow from a sarangi to play a Fender Jimi Hendrix guitar to give that dramatic touch,” said Rijal with a smile.

Discovery and Excitement

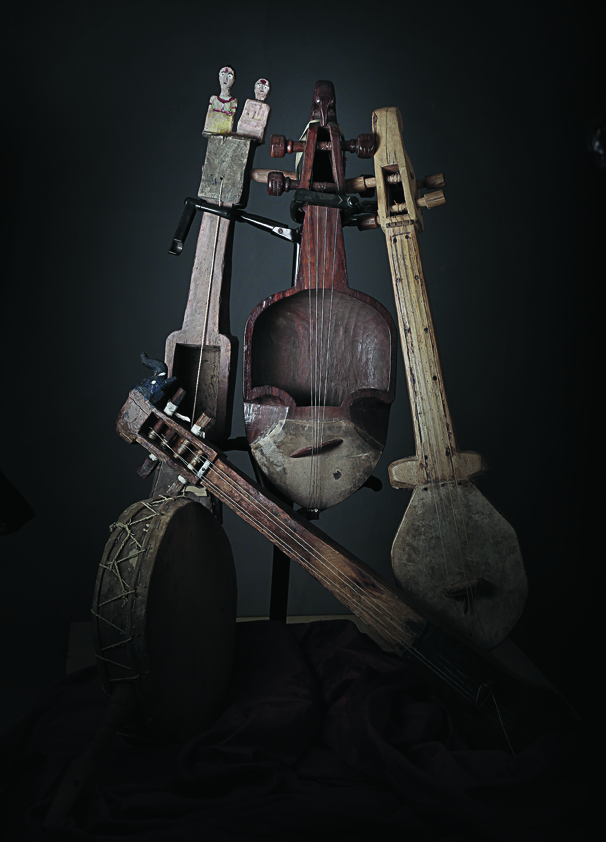

But, the most exciting part of the trip for Rijal wasn't the coming together of different musicians, as important as that was. It was the discovery of two musical instruments that people thought no longer existed. Many scholars who had studied and done research on folk music believed that the musical instruments phanderwanam and katwanam were now extinct, which made Rijal's discovery entrancing, and a fascinating story.

While recording with the Santhal musicians for his song in Haldibaari village in Jhapa district, one of the musicians talked about an old man who was in the construction business, but was also an instrument maker, and said that he could build a phanderwanam and katwanam.

Rijal traveled to five villages in search of this maker of musical instruments many believed no longer existed. He had almost given up, when he met a guy at a tea shop. He said that he knew the instrument maker. Rijal got on the man's motorcycle, and they drove to the place. There, he met the old man, who was perhaps the last person to possess the knowledge of instruments lost to history. When asked about the instruments, the old man went inside his house and brought out two musical instruments that were in a sorry state. After Rijal asked him, the old man somewhat restored them.

“He said he used to receive orders to make them in the past. I asked him if they were for sale. He was ready to sell it for 400 to 500 rupees, which was a sad reflection of the life of the instrument makers in our country.”

Phanderwanam and katwanam belong to the Chordophones family, which is a family of instruments that use vibrating strings to create sound. Chordophones are divided into different types, such as harps, zithers, lutes, lyres, and musical bows. They are defined by the bond between the strings and the resonator. Their history stretches back to medieval times, when minstrels performed songs using these instruments. Their songs narrated stories about far-flung places, or about real or imaginary people. Phanderwanam and katwanam were played mostly in the Middle East, Far East Asia, and Central Asia. In Nepal, they mostly came from the Hindu Kush region. A small section of the Santhal community migrated from Jharkhand and settled in Jhapa. They lived like nomads, traveling to different places, playing their traditional music and singing songs. They probably couldn't fit into the traditional definition of Nepali music, and so gradually disappeared.

A phantarwanam looks a lot like arbajo, smaller in size, with four strings made out of single piece of wood. It has an elephant carved at the top. The elephant probably signifies the Santhals’ closeness to nature. Katwanam has just one string, but looks like a sarangi, with a figure of a couple at the top belonging to the Santhal community. Rijal has used these instruments in his song ‘Nepali,’ too, but believes there is a long way to go in order to revive such rare instruments.

“I feel happy that I went to the community, did field recordings, and created some beautiful music. The instruments shouldn't be simply showcased in museums. They should be used for scholarly study. Their application should be recorded.”

Dr. Lochan Rijal, now a married man with a daughter, says a long difficult road lies ahead. “My dream is to collaborate with musicians from the 125 castes and ethnic communities all across Nepal. I want to do it in my lifetime. I also want to collaborate with world class musicians from across the world like I recently collaborated with Leon Jervis for my album KaachoAwaz.” Rijal believes the songs he has written and composed, about things he has envisioned or witnessed, define his life.

He believes the highlight of his career was the day he discovered that he did not know much about music, because it was the day he learned that he needed to explore music. Back in Kathmandu, he gently plays the instruments once broken and forgotten, a high tone rising and falling, as Rijal’s fingers move along the strings, creating sound not many have heard, a sound impossible to explain, but really worth listening to, and once heard, impossible to forget.