Barbara Adams and I were friends for more than 30 years until her death in Kathmandu in April 2016, two days shy of her 85th birthday. She was 13 years my senior; I called her Barbara Didi. Wags called her the Kanchi Maharani (the Junior Princess) and much later, in her “Maoist period,” the Kanchi Lal Maharani (the Red Junior Princess). She had lived in Nepal since 1961, six years before my own arrival in what was then the world’s only the Hindu Kingdom. Although our worlds eventually became tangled up together, our original paths to Nepal and through Nepal hardly ever crossed and could not have been more different.

I was a Peace Corps Volunteer (PCV) from 1967-70, a Junior Technical Assistant, posted near Janakpur and later in Nuwakot, laboring in His Majesty King Mahendra’s Agriculture Department. I’d heard tales about the glamorous American woman who’d come to Nepal and become the lover, or mistress (sophisticates referred to her as “the consort”) of Prince Basundhara, the youngest brother of King Mahendra, then Nepal’s absolute monarch. Word was that this American and her prince lived in a palace, hosted glamorous parties for diplomats, spies and royalty and knew everybody who was anybody. Her name, I would later learn, was Barbara Adams and her “palace” was actually a new house in Tahachal designed by the Swiss architect Robert Weise. But no matter, we might as well have lived on different planets.

I was a Peace Corps Volunteer (PCV) from 1967-70, a Junior Technical Assistant, posted near Janakpur and later in Nuwakot, laboring in His Majesty King Mahendra’s Agriculture Department. I’d heard tales about the glamorous American woman who’d come to Nepal and become the lover, or mistress (sophisticates referred to her as “the consort”) of Prince Basundhara, the youngest brother of King Mahendra, then Nepal’s absolute monarch. Word was that this American and her prince lived in a palace, hosted glamorous parties for diplomats, spies and royalty and knew everybody who was anybody. Her name, I would later learn, was Barbara Adams and her “palace” was actually a new house in Tahachal designed by the Swiss architect Robert Weise. But no matter, we might as well have lived on different planets.

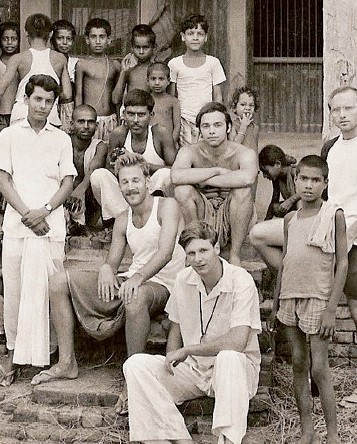

As a PCV, I was intent on ‘gettin’ down with the people,’ so I ate only by hand, wore rubber chappals (purchased from the Bata store on New Road, the only place in the kingdom that sold shoes big enough to fit me) and affected a bizarre combination of western and Nepali village dress – flared khaki shorts or pajamas and khadi kurtas. I seldom visited Kathmandu. When I did come to the capitol, I would hang out in Maruhiti Tol, or at the old Peace Restaurant on Lazimpath, Nepal’s first Chinese restaurant. In those pre-terrorized days, when all you needed to get into the American Embassy was to flash your US passport, the closest I ever got to an elite party was the annual 4th of July picnic at the American Ambassador’s Residence in Kamaladi. I would eat hot dogs and potato chips and drink Buds there along with other PCVs and miscellaneous American citizens before being cast out again into the streets of Kathmandu.

Barbara Didi’s world of glittering parties, diplomatic soirées, palace intrigue, tiger hunts and pig sticking and my gaunle world of the 1960s did intersect just once in 1967. I was in Kathmandu for a workshop and one foggy winter morning I saw her riding a fine white horse down the dirt road that leads south from the gates of Narayanhiti Palace. ‘Wow,’ I thought to myself, ‘Ain’t she somethin’?!’ However it wasn’t until about 1983 that Barbara Didi and I met in person and became friends. Kathmandu no longer seems to have foggy winter mornings and that dirt road, now paved and lined with luxury shops, is known as Durbar Marg.

Our friendship had its ups and downs. We had quite different backgrounds and temperaments. But at the end of the day, we managed to keep it going, perhaps because our politics overlapped – at least in principle – but more importantly because of our shared love for Nepal. Also because over the years our very lives became intertwined, like braided rivers, in two magical worlds: Nepal and New York, specifically the North Fork of Long Island, a picturesque seaside community three hours east of New York City.

Our friendship had its ups and downs. We had quite different backgrounds and temperaments. But at the end of the day, we managed to keep it going, perhaps because our politics overlapped – at least in principle – but more importantly because of our shared love for Nepal. Also because over the years our very lives became intertwined, like braided rivers, in two magical worlds: Nepal and New York, specifically the North Fork of Long Island, a picturesque seaside community three hours east of New York City.

Due to some strange alignment of the planets, it so happens that the North Fork was not only Barbara Didi’s American home, but also my sasurali, my wife Barbara Butterworth’s family home and also that of Pam Ross and Charles Gay, another couple of long time residents of Kathmandu. My wife Barbara’s and Pam’s families were among the original English settlers in the New World, arriving on the North Fork in the 1640s. Barbara Adams’s roots on the North Fork were rather more recent, dating to 1910.

In that year Barbara Adams’s great-grandfather and several New York artist friends with whom he had studied at the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris “discovered” the North Fork. They built houses and studios and spent the summers there picnicking, sailing and, most notably, painting. Collectively, they became known as the Peconic Bay School, essentially American impressionists and post-impressionist painters whose work is now much prized. Barbara Didi spent her childhood summers there and in the 1970s she inherited a little cottage that had been part of her great-grandfather’s property. It was an art-filled, witty, utterly ramshackle place that stood on a wooded lot on a bluff above Peconic Bay. During her last decades she held court there for a month or two each summer.

In that year Barbara Adams’s great-grandfather and several New York artist friends with whom he had studied at the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris “discovered” the North Fork. They built houses and studios and spent the summers there picnicking, sailing and, most notably, painting. Collectively, they became known as the Peconic Bay School, essentially American impressionists and post-impressionist painters whose work is now much prized. Barbara Didi spent her childhood summers there and in the 1970s she inherited a little cottage that had been part of her great-grandfather’s property. It was an art-filled, witty, utterly ramshackle place that stood on a wooded lot on a bluff above Peconic Bay. During her last decades she held court there for a month or two each summer.

I have been summering with my wife Barbara on the North Fork since 1982 and we now live there full-time. Our home, Pam and Charles’s home and Barbara Adams’s cottage are sprinkled along the same shoreline of Peconic Bay and it was there in 1983 that Barbara Didi and I finally met in person, more than a decade after that foggy morn when I saw her on her cantering along Durbar Marg. Our friendship deepened after my wife Barbara and I returned to Nepal in 1986. We entertained each other frequently in Kathmandu and during the summers in New York. My Barbara and I would often invite Barbara Didi to go sailing with us, and Pam and Charles would often join us. Afterwards, we would go to Barbara Didi’s cottage, sip gin and tonics on the bluff overlooking the bay and end up at our house for dinner. We rarely ate at her place, since Barbara Didi could barely boil water, much less cook anything palatable.

In notes for an unpublished memoir, Barbara Didi recounts her arrival in Kathmandu in February of 1961, ostensibly to write a story for an Italian magazine on Queen Elizabeth’s visit to Nepal. For whatever reason, the Queen Elizabeth story was never written, but another kind of royalty awaited Barbara Adams in Kathmandu. Not long after her arrival, she was invited to the Yak & Yeti one night by:

. . . two Texas millionaires . . . both self-proclaimed big-game hunters. It was at the Royal Hotel's famous Yak and Yeti bar . . . that . . . picturesque, cozy, uniquely Nepali drinking lounge, that I first met Prince Basundhara Bir Bikram Shah Dev, otherwise known as Kancha Sarkar, or the Third Prince . . . After dinner with my Texas millionaires, we all trekked down the marble corridor to a wonderful, softly lit room . . .

This Yak & Yeti Chimney Bar, inside the old Royal Hotel on Kantipath, is to be distinguished from today’s five star hotel of the same name, which was built only in the 1980s. The Royal Hotel was converted in 1951 from Bahadur Bhawan, a former Rana palace. From the 1950s until the late 1960s, when the Hotel de L’Annapurna and shortly afterwards the Soaltee were completed, the Royal was Nepal’s sole international standard hotel. Its Yak & Yeti Chimney Bar was the watering hole for Nepali aristocrats, the diplomatic corps, spies and the few well-heeled travelers who made it to Nepal in the days before the advent of industrialized, mass tourism.

The Royal was owned by Prince Basundhara and managed by the legendary Boris Lisanevich, a White Russian émigré and onetime Ballet Russe dancer who had run the famous 300 Club in Calcutta, a nightspot favored by the subcontinental princely class. There, Boris had befriended King Mahendra’s father, King Tribhuvan. With the restoration of monarchical rule and Tribhuvan’s return to the throne in 1951, Boris came along to Kathmandu as Mahendra’s chef de protocol. The Royal Hotel is long gone, but the building still stands and now houses Nepal’s Election Commission.

The Royal was owned by Prince Basundhara and managed by the legendary Boris Lisanevich, a White Russian émigré and onetime Ballet Russe dancer who had run the famous 300 Club in Calcutta, a nightspot favored by the subcontinental princely class. There, Boris had befriended King Mahendra’s father, King Tribhuvan. With the restoration of monarchical rule and Tribhuvan’s return to the throne in 1951, Boris came along to Kathmandu as Mahendra’s chef de protocol. The Royal Hotel is long gone, but the building still stands and now houses Nepal’s Election Commission.

Barbara’s memoir notes continue:

I sat by the fire with my companions . . . Suddenly someone plunked himself down in the empty chair across from me, and started to talk about something about which I could never have known or discussed. Seeing my startled look, he said: "Oh I'm sorry! I thought you were someone else!" It seems that while he had gotten up and gone to the men's room, the woman in the chair opposite had left. He somehow didn’t realize, in that candle and firelight lit room, that I was not the same Memsahib, and went on talking as though I were she!! . . . Anyway the conversation bloomed and turned to tiger hunting, which I remember as being both disturbing and exotic . . . Tiger hunting was almost the national sport in which the Royals and the Ranas enthusiastically indulged . . . Awareness of [the] need to protect "endangered species" had not yet entered public consciousness and talk of tiger hunting began to seem perfectly natural. Participating in one came a few years afterwards!

Following after-dinner drinks at the bar, Barbara and her millionaire big game hunter companions were all invited for more drinks and conversation at the Prince’s home in Kalimati. At evening’s end she was:

. . . deposited at the unprepossessing Imperial hotel and I somehow found my way through the sweet smelling darkness to my room, where I lay awake, my head full of images, fragments of conversation, and above all questions about the perceived loneliness of a Prince who appeared to have everything!

No doubt Barbara believed that this ‘lonely’ prince with his classic pickup line about mistaken identity “who appeared to have everything,” lacked only a good woman who could truly understand and love him as a man, not merely a prince! (Perhaps . . . she must have thought, she might be that woman!) In the event, one thing soon led to another and within months, after a clandestine trip to Hong Kong, Barbara and her prince returned to Kathmandu as a couple.

So life went along . . . lots of picnics, lots of parties, lots of meeting new people and lots of nervousness when actually confronted with, or having to plan on meeting, members of the Royal family . . .

Although Barbara and Basundhara may have been, as she puts it, “treated like a married couple” by their friends, they never formally tied the knot. Basundhara had already been married at least twice (possibly thrice), before he happened upon Barbara at the Yak & Yeti. Not surprisingly affairs among the aristocracy were common. In her notes, Barbara writes:

Although Barbara and Basundhara may have been, as she puts it, “treated like a married couple” by their friends, they never formally tied the knot. Basundhara had already been married at least twice (possibly thrice), before he happened upon Barbara at the Yak & Yeti. Not surprisingly affairs among the aristocracy were common. In her notes, Barbara writes:

The improbable alliances and misalliances were so frequent, so visible . . . I frequently speculated on what the reaction would be among Nepalis if someone should write a Nepali version of the much talked about Peyton Place, then a hit in America. Could it be called Kathman do or don't! or naughty in Naxal? etc. etc.

The British writer and barrister Neville Sarony lived in Kathmandu during this period and knew both Barbara and Basundhara well. In “Counsel in the Clouds,” his marvelous new memoir, he describes tensions between Barbara and Basundhara even in the late 1960s. Nonetheless, she and the prince remained together for at least a decade, when he left her for another woman. He died in 1977. Whatever the truth was about their relationship and its end, Barbara prominently displayed photographs of Prince Basundhara in her homes in Kathmandu and on Long Island until the day she died.

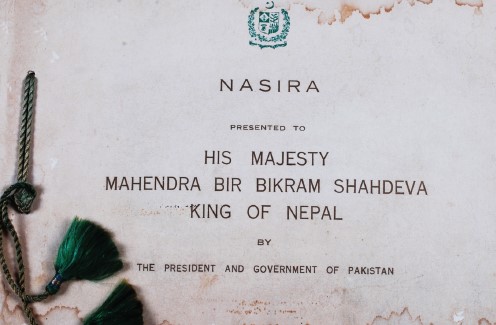

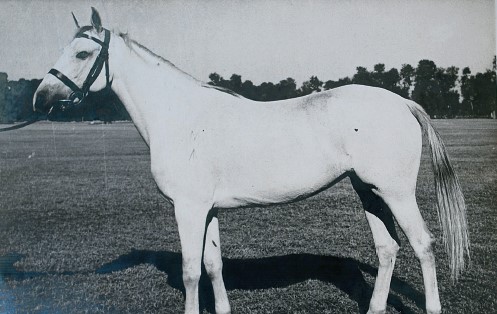

A few years before she died, Barbara Didi told me about that white horse. She was an Arabian mare called Nasira, a gift from Ayub Khan, then the President of Pakistan, to King Mahendra. Fortunately for Barbara, however, the king’s astrologers, citing some inauspicious markings on the beast, advised him not to keep the animal. So Mahendra passed Nasira on to Prince Basundhara, who in turn gifted her to Barbara. It was an entirely appropriate gift, because Barbara Didi was an accomplished equestrienne. Barbara’s favored vehicles included not only the mare Nasira, but also a sporty white Sunbeam Alpine two-seater, another gift to her from Basundhara, that she would drive through the city with her long hair flying in the wind.

The Shah kings were believed by some to be Lord Vishnu incarnate. As someone who was associated with Nepal’s royal family, it is perhaps fitting that some of Barbara’s baahans, or vehicles, were famously associated with her, much as Vishnu has Garuda, Brahma his seven swans, Durga her lion and Lord Ganesh, rather incongruously, a shrew.

The Shah kings were believed by some to be Lord Vishnu incarnate. As someone who was associated with Nepal’s royal family, it is perhaps fitting that some of Barbara’s baahans, or vehicles, were famously associated with her, much as Vishnu has Garuda, Brahma his seven swans, Durga her lion and Lord Ganesh, rather incongruously, a shrew.

Alas, Barbara’s final baahan was neither a prancing Arabian nor a spiffy two-seater, but rather quite prosaic 21 year-old Suzuki jeep. I know about that car only too well because after she died, I sold it. But that story comes a bit later in my little tale.

My wife Barbara Butterworth was also a Peace Corps Volunteer in Nepal in the 1960s, but we met only in 1982, in California. By 1984, when we married and both of us had earned doctoral degrees, in law and education, we were eager to return to Nepal together. We moved back to Kathmandu in late 1985. Barbara worked as a USAID advisor to the Ministry of Education and I as a consultant at New ERA and at Nepal’s Women’s Legal Services Project. My work in Nepal’s legal system brought me into contact with a number of Nepali lawyers and activists who were more or less openly working to overthrow the one-party Panchayat system and reestablish parliamentary democracy, a goal with which I sympathized. We took a house in Bishalnagar, not far from Barbara Didi’s home in Hattisar, which really did qualify as a palace. We saw Barbara Didi often, especially when we hid her in our house from the Queen. But before I get to that, we need a bit of history, both American and Nepali.

Barbara Adams came from a family of New York City and Washington DC Democrats with liberal, if not progressive roots. Her economist father had worked in FDR’s administration and had played a key role in developing evidence to prosecute Nazis in the Nuremburg Trials. So it was unsurprising that Barbara experienced some guilty discomfort about certain aspects of her “royal” life. In her journal she wrote:

When people ask me how an American as intrinsically democratic as I could have spent so many years with Basundhara, I always reply that he was in his own way, as democratic as I. He had no pretenses, was friendly with everyone, stood up whenever any new person entered the room . . . and generally treated everyone as equal . . . Looking back it seems that the life we were leading was almost immoral in its luxuriousness and the ease with which we found people to do all the hard work, but I did not openly question then. I kept my questions and my feeling of guilt to [myself].

Now fast forward again to the late 1980s. Nepal, along with much of Eastern Europe, was boiling with political ferment. After Basundhara’s death, Barbara Didi’s politics had shifted back from quasi-royalist to liberal-progressive, eventually becoming even fashionably quasi-revolutionary. Somewhat incongruously, given her declared politics, Barbara continued to live in royal style in a large and beautiful Rana era home in Hattisar. The place was a veritable museum. Barbara had exquisite taste and she combined gifts from Prince Basundhara with her earnings from the travel business (she was one of the early promoters of high end tourism in Nepal), journalism and an inheritance from her father to amass a formidable art collection of traditional and modern pieces by Nepali artists as well as hundreds of Bhutanese textiles. Many of these works were on prominent display in her Hattisar home, where she lived for almost the entire last 30 years of her life. Her Hattisar palace also had one of the most beautiful gardens in Kathmandu, a perfect venue for her salons and garden parties. She seemed to know every ambassador in town and for years she entertained the Who’s Who of Nepal’s artistic, intellectual, political, diplomatic and expat communities.

By the late 1980s, Nepali democrats’ calls for an end to the Panchayat system had become increasingly open and bold. King Birendra was not nearly as clever, ruthless or as determined as his father Mahendra had been in stamping out the democratic political opposition, which went from strength to strength. As this democratic movement began, the American Embassy’s position on supporting these developments was rather timid at best, but Barbara Didi was right in the thick of calling for restoring multi-party democracy and a shift to constitutional monarchy.

Barbara had dabbled in journalism throughout her adult life and by the late 1980s she was writing about, meeting with and encouraging the young (and not-so-young) Nepali democrats – lawyers, journalists, politicians and human rights activists who wanted to overthrow the Panchayat system. Her journalistic and other activities put her at odds with the palace, especially Queen Aishwarya, who seemed to have a particular dislike of her, perhaps dating back to her scandalous affair with Kancha Sarkar. In any event, in 1988, Barbara Didi crossed some invisible line and the Queen ordered that she be put under house arrest and deported.

A week or so after Barbara was put under house arrest, a stranger showed up one Saturday morning at the house in Bishalnagar that I shared with my wife Barbara and our infant son Peter. The stranger’s head was crowned with a towering blonde bouffant hairdo and she wore a short pleated skirt, saddle shoes and sunglasses. An ancient Leica camera dangled from her neck and jiggled over her ample bosom. She looked like a cross between a deranged tourist and an aged American high school cheerleader. Without so much as a by-your-leave, she barged into our house, tore off the bouffant wig and breathlessly poured out the story of her outrageous (as she saw it) persecution by the Queen. It was of course Barbara Didi.

She spent the next week in hiding at our house, refusing to even go into the garden for fear of being seen and recognized, banging out petitions to the King on our primitive desktop computer, and beseeching her old friend Rishikesh Shah, the aristocratic diplomat, scholar and human rights activist, to see if he could have her arrest quashed. Her entreaties were unsuccessful, but when at last she was finally deported, it was done in style. Milton Frank, a notorious American ambassador, drove her to the airport in his Ford Thunderbird and personally escorted her onto the Delhi flight via the VIP lounge. That was Barbara Didi’s first forced exile from Nepal.

After the First Jan Andolan and the restoration of constitutional monarchy in 1990, Barbara was let back into the country through the intercession of powerful friends and after promising to “behave herself.” There would be another deportation, in 1998, this one during one of the Congress governments of Girija Prasad Koirala, as Barbara’s occasional columns in Jan Astha became more and more sympathetic to the Maoists. Finally, however, in 2009, after the Maoists won a plurality in the elections and formed their first government, Barbara’s long-standing wish to become a naturalized Nepali citizen was granted. She died a proud Nepali citizen in 2016.

After a few years back in the US in the early 1990s, my wife Barbara and I returned to Kathmandu in 1998. I served as the Executive Director of the Fulbright Commission and Barbara as Director of Lincoln School. Even after our formal work in Nepal ended, we returned to Nepal every winter for 3-4 months. We remained close to Barbara Didi, seeing her often, both in Kathmandu and in New York.

A couple of years before Barbara Adams’s death, I learned from a mutual friend that some years earlier, without consulting me, she had named me in her will as her executor. (Under American law, the executor has the often-unenviable responsibility of wrapping up the deceased’s financial affairs, disposing of her property and ensuring that the proceeds are distributed according to her will.) Barbara Didi’s personal affairs were complicated, to say the least: art collections in Nepal, more art and houses in New York and Washington DC. I was furious that she had foisted this responsibility on me without the courtesy of even asking me whether I was willing to do so. Alas, that was rather typical of Barbara. For months, I wrestled with telling her that she should find someone else to take on the job. Suddenly, in February 2015, she suffered a major heart attack and then it was too late for me to change my mind.

Ironically, Barbara’s good luck and panache extended even to her sudden illness. Her heart attack occurred at a book launch to celebrate the publication of “Himalayan Style,” Thomas Kelly’s and Claire Burkerts’s lavish coffee table book. Among other homes, the book featured Barbara Didi’s own Hattisar Durbar. She was also fortunate to have collapsed into the arms of a good friend and that the American Ambassador was also in attendance, as were two wonderful US Embassy nurses, who immediately deployed the Ambassador’s AED device to jolt her back to life.

Her recovery, however, was horrendously difficult. Two months after her heart attack, the April 2015 earthquake struck when she was still in the ICU at Kathmandu’s Grande Hospital. She spent several nights in the hospital’s parking lot before being medivacked by air ambulance to New Delhi, where she remained in hospital for another three months. During this entire time, her daily needs were looked after by her two long-term household staff, Johnny Karki and Maya Gurung. Although much diminished physically, including loss of sight in one eye, Barbara eventually returned to Nepal and made the most of her last 14 months of life in her adopted country.

I was in New York when the news came of Barbara Didi’s passing. I flew to Kathmandu a week after she was cremated at the new electric crematorium at Pashupatinath. (Environmental advocate that she was, Barbara Didi would have been proud to know that she has the distinction of being the first non-native of Nepal whose remains were so disposed of.) Half of her ashes were scattered on the Bagmati and half on her beloved Peconic Bay off Eastern Long Island.

Barbara Didi’s will directed that all proceeds from her estate be distributed among two long-time servants and two foundations that work in Nepal. Fittingly for someone who loved Nepal as much as she did, every rupee, mohar, paisa and sukaa has, or will be, repatriated to Nepal.

With the invaluable assistance of Barbara’s household staff and several of her old friends, especially Maya Gurung and Frances Howland, I obtained death certificates from the government of Nepal and the US Embassy and attended memorial gatherings. We took stock of her all of her possessions and art collection in Nepal and over the next year, we sold it all, including that Suzuki jeep, Barbara Didi’s last baahan. Barbara’s affairs in the US remain to be settled. But in Nepal at least, however reluctantly, I have done my duty and our intertwining paths through Nepal have come to an end.

USA vs. USSR?

In 1963, John Kenneth Galbraith, the Harvard economist whom President John F. Kennedy had appointed as US Ambassador to India, traveled to Kathmandu to visit his friend Henry Stebbins, the first resident American Ambassador in Nepal. Galbraith was already acquainted with Barbara Adams, probably through her father, an economist who held a string of high-level government positions in several Democratic US administrations. Barbara had apparently also met Galbraith in Rome, where Barbara was briefly married to an Italian dentist, before coming to Nepal in 1961. In his “Ambassador’s Journal,” Galbraith’s own memoir of the period, he writes of meeting Barbara in Kathmandu on April 5th 1963, at a dinner in Singha Durbar:

Barbara Adams, a charming friend whom I had not seen for several years, is here in Kathmandu. She is a handsome, intelligent girl in her late twenties (in fact she was then 34) who arrived here a couple of years ago with her Italian husband. They were later divorced and she, in turn, settled down as a member of the royal family. Stebbins [the American Ambassador] considers her a fine influence.

The Italian marriage was apparently a short one and ended with a Nevada divorce decree not long after Barbara’s arrival in Nepal. In her memoir, “the Italian” receives nary a word of mention. A year before she fell ill, I asked Barbara about this entry in Galbraith’s journal. Her only response, before abruptly shifting the conversation to another topic was: “I wish Galbraith hadn’t mentioned the Italian.” It’s anyone’s guess what Ambassador Stebbins meant by his comment regarding Barbara Didi’s salutary “influence.”

The Italian marriage was apparently a short one and ended with a Nevada divorce decree not long after Barbara’s arrival in Nepal. In her memoir, “the Italian” receives nary a word of mention. A year before she fell ill, I asked Barbara about this entry in Galbraith’s journal. Her only response, before abruptly shifting the conversation to another topic was: “I wish Galbraith hadn’t mentioned the Italian.” It’s anyone’s guess what Ambassador Stebbins meant by his comment regarding Barbara Didi’s salutary “influence.”

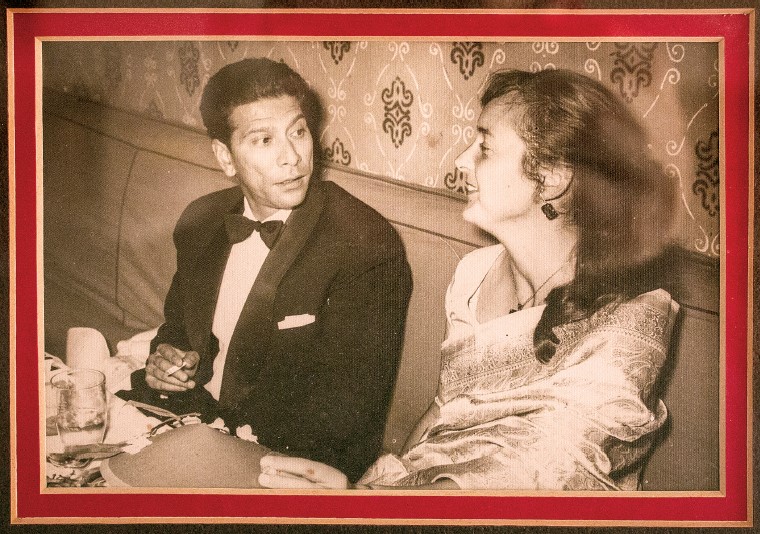

Barbara Didi described herself as a “painfully shy” teenager, but judging from photos of her taken in the 1960s, any signs of awkwardness had by then long disappeared. One of my favorites shows her in a fine sari, a strikingly handsome woman, with her prince by her side, chatting with the military attaché from the Soviet Embassy. I wonder if the Russians also thought of her as a “fine influence” on the House of Shah.