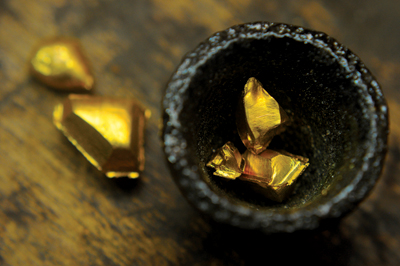

Gold represents prosperity yes, but also a way of life and continuity of family traditions for the Newars of the Kathmandu Valley.

It all started with a wedding. In Syamukapu, D.S. Kansakar Hilker writes, “Around the early 7th century A.D., the Lichhavi king of Nepal, Amsuvarma had his daughter Bhrikuti married to Srong Tsang Gampo, the king of Tibet, and as part of her dowry, a troupe of skilled craftsmen travelled with her to Tibet.” Some historians state that there were traders along with the artisans that were sent off to Tibet with the Nepalese princess.The marriage was performed to benefit the diplomatic relationship between the two countries.However, the Tibetan king also married a Chinese princess since he had to be friends with China as well.Due to this, trade also developed between Nepal, Tibet and China, with Nepali merchants going to China via Tibet and vice versa.

In Jewels of Newar Art, Dina Bangdel writes, “By the Licchavi period (4th-9th century), Nepali craftsmen had developed distinctive stylistic and aesthetic conventions in both metal and stone sculptures, rivaling their Indian counterparts of the Gupta period. These masters – the Newar artists of the Kathmandu Valley – quickly achieved international repute throughout Asia, and were acclaimed as world class painters and sculptors with unparalleled skill and iconographic expertise.” The most famous Newar artist is perhaps Arniko. He was first invited to go to Tibet in 1260 to build a golden stupa in Tibet with a team of 80 artisans. In 1482, a trade treaty was drawn up by which the traders of the Kathmandu Valley were permitted to open business houses in Tibet and also to settle there. It also stated that all the trade between India and Tibet be routed through Nepal.

In Jewels of Newar Art, Dina Bangdel writes, “By the Licchavi period (4th-9th century), Nepali craftsmen had developed distinctive stylistic and aesthetic conventions in both metal and stone sculptures, rivaling their Indian counterparts of the Gupta period. These masters – the Newar artists of the Kathmandu Valley – quickly achieved international repute throughout Asia, and were acclaimed as world class painters and sculptors with unparalleled skill and iconographic expertise.” The most famous Newar artist is perhaps Arniko. He was first invited to go to Tibet in 1260 to build a golden stupa in Tibet with a team of 80 artisans. In 1482, a trade treaty was drawn up by which the traders of the Kathmandu Valley were permitted to open business houses in Tibet and also to settle there. It also stated that all the trade between India and Tibet be routed through Nepal.

The treaty was renewed from time to time and it was the result of one of those treaties that caused the inflow of Tibetan gold and silver into Nepal. Newar traders exported finished products from Nepal and India to Tibet and brought back goods from Tibet and other parts of Central Asia. The middlemen for all this trade were the Newars of Kathmandu; people with surnames like Kansakar, Tamrakar, Vajracharya, Tuladhar, Shakya, Dhakhwa and Shrestha, who established themselves in Kalimpong and Lhasa. On their return journey, the mule trains brought back yak tail, yak wool, silver bars, gold dust, Tibetan block tea, carpets, thangkas, Chinese silk, chinaware and semi-precious stones. Gold was found in the rivers of Tibet and even on the surface in some areas. Dinafurther writes, “For the Buddhist clientele, the Newar Buddhist caste groups of Vajracharyas and Shakyas were the Valley’s craftsmen: carvers of stone, wood and ivory; painters; and highly skilled metalworkers, goldsmiths, and silversmiths. These occupations led many members of these caste groups to serve as itinerant artists in Tibet, commissioned to work for monasteries throughout central and southern Tibet.”

Cultural and contemporary value

It is believed that to the Newars, jewelry is a form of amulet, worn to strengthen their health and fate. Sushila Manandhar writes in Supernatural Power of Body Adornment: Beliefs and Practices among the Newars of Kathmandu Valley (Nepal): “Newars utilize amulets jantara or yantra (lit: tool) for relief from sickness to protect themselves against evil spirits or to accumulate divine power. Those amulets contain either an image of a deity or it’s ‘charms’, mantras. Pyucha, a pair of gold bracelets, worn by Newar children is believed to fortify and protect the soul of the child.”Also, gold itself is supposed to work as an antiseptic. Furthermore, Manandhar explains, “Newars use a tiny cylindrical locket, called tayo for relief from mental and physical illness. A cylindrical shaped gold locket called the pragyaparamita jantar is very popular among the Buddhist Newars. It is believed that the person who wears it gains knowledge and wisdom. Most of the material used in making ornaments and jewelry is supposed to possess divine power and represent the deities or planets. Sometimes the motifs depicted on them play a vital role in providing such power.

These adornments look good on one hand and also provide strength, health and protection against evil spirits on the other. It is believed that by wearing them, people can accumulate extra energy.” In Nepalese Culture in a Nutshell, Dr. Ram Dayal Rakesh writes, “The link between ornaments and religion is strong. Hindus associate gold with Lakshmi, the goddess of wealth and others perceive it as a symbol of the sun. Like the sun, gold too is held to be immortal and sacred.”

In The Power of Gold, The History of an Obsession, Peter L. Bernstein stresses how people have become intoxicated, obsessed, haunted, humbled, and exalted over pieces of metal called gold. From poor King Midas who was overwhelmed by it to Aly Khan who gave away his weight in gold every year, gold has held everyone captive.

Moreover, gold is imperishable. Its radiance is forever. The density of gold means that even very small amounts can function as money of large denominations. Gold is taken as a store of monetary value. It is a good source of investment, a symbol of beauty, and an indicator of the socio-economic status of the wearer.

Before and Now

Before and Now

“Because the gold traders didn’t have many clients inside the valley and the clientele was saturated, the situation necessitated the Valley’s goldsmiths to find new customers, so they went far and wide,” informs Rabindra Bajracharya. Also, some would travel during particular times of the year with the ready-made designs, make the sale or take orders and come back home. Rabindra’s grandfather however, went to Trishuli leaving their ancestral house in Patan. It was only in 2000 that the family resettled in Patan. Rabindra Bajracharya’s family has been involved in this business for as long as he can remember. After the death of their father, he and his younger brother now run Lalitpur Ornaments in Patan’s Gabahal.

“We are originally from Banepa. I started this shop here in 1994,” says Amogha Ratna Shakya about his shop in Kathmandu’s Kalimati. He informs that there were just two other goldsmiths when he opened shop here. “There is not a place inside the country where the valley Newars have not been,” he adds. In Newar Society, City, Village and Periphery, Gerard Toffin writes, “It is worth noting that many Newars have left the Kathmandu Valley over the centuries and have long lived in other parts of Nepal, especially in towns that are marketplaces, to the east, the west and the south: Dolakha, Tansen, Pokhara, Bandipur, Nuwakot-Trishuli, Bhairahawa, Dhading. Some Newars also live in Tibet (Lhasa, Shigatse), Sikkim, Darjeeling, Kalimpong, Dehradun, and other parts of North India.”

“There were goldsmiths only in Hakha and Gabahal of Patan but now there are more than I can count,” says Uttam Raj Shakya about a profession that has flourished over the years. The job earlier designated only to Shakyas and Vajracharyas is now adopted by practically everyone who shares the business acumen.Earlier ornaments were made only ‘on order’. There were no fancy shops. Goldsmiths worked from their homes and entertained their customers from the comfort of their house. According to Amogha Ratna Shakya, the display culture started from the capital. Before, everything was done by hand. Machinery hadn’t gotten here yet. Every piece spoke volumes of the artistry of the goldsmith, told a story and wasproof of the supremacy of the makers.

Such was the prowess of Nepali craftsmen that Berenice Geoffroy-Schneiter in Asian Jewellery writes, “By the early 1960s the shops in New Delhi, Kathmandu or Kabul were like Ali Baba’s cave: fibulae, wedding headdresses, torques and bracelets were displayed before the amazed eyes of the travelers. But only a few were capable of recognizing in these jewels, seeming to come down from Antiquity or the Middle Ages, the symbolic value of their materials and their decoration, the extraordinary graphic beauty of their arabesques or scrolls.”

After the invasion of modernity, customers and makers both forsook traditional designs. Buying and selling of designs from borrowed cultures became a trend. People started selling their grandmothers’ jewelry and instead collected ornaments with new designs. The cultural significance of the designs were ignored, forgotten even to some extent.

Taking hints from the high cost of gold, people look for designs that are a combination of gold and pearl, gold and diamond, or gold and any other stone. Compared to the past, people these days opt for 22K and 18K gold designs. As far as Uttam Raj Shakya’s memory goes, the lowest and highest prices for a tola (11.66gm) of gold has been Rs.200 Rs.63000 respectively. However, even that didn’t dampen the mood of the people from buying gold. Such is the craze.

It is interesting to note that much of the new-age jewelry that we use today is actually made by skilled Bengali craftsmen employed by many goldsmiths. “They are good at their job, they meet deadlines and they have trained hands,” echo Kathmandu’s gold merchants. Take for example Tappan Kumar Maiti, who came to Nepal with his brother-in-law.The Bengali artisan has been working for 22 years at Uttam Raj’s shop. Indian designs are in demand in the market and thus the popularity of the Bengali artisans.

Resurrection of the traditional

Tides are turning though. There has been a revival of sorts concerning old ornaments like the Chandrama clip (moon-shaped hair clip), Charpate Jantar (the rectangular talisman) and the Chandra Haar (moon shaped necklace). An interesting cultural development is that many of the designs that were only worn by people of a certain caste before are now worn by all. If you can afford to buy it, you can wear it, seems to be the message. The cultural segregation is largely absent today. Rabindra Bajracharya attributes some of this as the revival of old designs, for the love of their roots by the Nepali diaspora. However, he is quick to add that the old designs are now revised, often infused with a contemporary touch. Along with this change in taste, is the change in how these pieces are being made.

Bijendra Shakya, Uttam Raj’sson, took me to his small factory where one wall was lined with small boxes. They each contained casts for jewelry. “It has been some time since I started delving in casting. It is easy and cost-effective. All you need to do is work on the finishing.” Amogha opines that the casting trend is profitable only if mass production is the target. “What will you do with hundreds of designs of the same kind? Until and unless you supply the design to others merchants, I don’t see a rationale behind it,” he says.

Like any other sector, there are uphill challenges in the trade and making of gold jewelry. From demands for increase in imports of gold that have landed on deaf ears to the black market that has taken root because of gold shortage, all of it hints at a decline in the trade of hand made gold jewelry. The loss would be of not just ornamVvents, trade and finances but also of an art form that symbolises a way of life and a level of craftmanship that has been cherished and respected the world over.

The Legacy Continues

Amogha Ratna Shakya was 14 when he started helping his father in his trade. His father came to the capital because of the business prospects it promised and also because he wanted to give his two sons a good education. Pancha & Sons, Amogha’s jewelry shop, echoes the strong sense of family and tradition through its name by mentioning that the business is run by the father and his children. Amogha has two sons: one who handles the major responsibilities of the shop now and a younger son, who is a software engineer and works at a software company. Had Amogha’s eldest not shown any interest in the family business, he would have had to sell the shop eventually. It is a business whose base is trust; understandably it is largely a family business still.

The culture of passed on business acumen and skills is something very close to the Nepali identity. It is about family and society; it even defies ‘modernity’ to some extent. In today’s world, where fathers and sons hardly spend much time together, the two generations at least exchanges remarks and share the same emotions even though with the pretext of the business. Because he walked the same path, the father can easily relate to the son’s problems and take pride in the fact that it was he who taught his son the tricks of the trade. All this allows the duo and their community to stay connected to their roots.

At Bijendra’s place, Uttam Raj & Sons, even if the shop boasts of catalogues of modern designs, he searched for designs by his father. The pride in his face is unmistakable. Uttam Raj Shakya started working at the age of 15; he is 72 now. He grew up observing his father play with the shining yellow metal. He learnt the tricks of the trade from his father and he instilled the same to his 29-year old son, Bijendra. It is crucial that the next generation shows interest in the family business;it shouldn’t die.If it does, with it a part of our culture too will see its demise.