When Dwarika Das Shrestha, the founder of Dwarika’s Hotel, came across a couple of woodworkers destroying an ancient carved pillar, little did he know he was looking at what would be a lifelong commitment to preserving his culture, and one that would pull in his family along with him.

It was a foggy winter morning in the early 1950s. Dwarika Das Shrestha was on his way home from an exercise session in Tundikhel, a part of his normal routine. Small groups dotted the square in Basantapur, huddled around tiny makeshift fires. Some gripped hot cups of tea while others had already started work. Dwarika was barely aware of his surroundings until his path was blocked by a couple of carpenters exerting themselves, sawing off a piece of wood and tossing it into a flame bit by bit. They weren’t doing anything out of the ordinary, but something wasn’t right. It took Dwarika a moment to realize that it was no ordinary wood they were working on; it was a pillar with Newari carvings, probably centuries old, and it was being fed to the fire. Now, Dwarika was a practical man. He was not a stickler for tradition, but he recognized loss when he saw it.

Dwarika was born in 1925 to Janak Das and Kanchhi Maiya Shrestha. He was the first of eight sons and two daughters, one of whom died young. Being the eldest child, responsibility was thrust upon him. For many, such pressures come as a roadblock in their search for individuality; it’s not uncommon to rebel under such duress. But Dwarika took on this burden wholeheartedly; it was also, perhaps, what shaped his personality. His father, the protagonist of a rags-to-riches story himself, wanted Dwarika educated; he wanted his oldest son to be in charge of the well-being of his siblings. The young boy was thus sent to Banaras in India for schooling at the tender age of eight. How he felt about it, or whether he even protested, we’ll never know, but it isn’t hard to fathom the misery that must have arisen from living far away from the warm hearth of home and the loving embrace of parents. To make matters worse, the family he lived with, relatives of his, turned out to be exceedingly strict. What the experience did, though, was instill in him a sense of responsibility, something he held throughout his life.

That morning, ironically under the looming shadow of the historic Hanuman Dhoka palace, as Dwarika stared at the charred pieces of ancient wood, he was appalled at the ignorance on display and the destruction of a culture he held so close to his heart. Carvings such as these took months to complete, and here was one being so mindlessly destroyed. Dwarika knew that change was inevitable; that modern structures would replace the old houses he grew up looking at. He was born in one, after all. It was then that the responsibility so ingrained in him came to the fore. At that moment, he made a decision that would change the course of his life. “Give me those old pillars, and I’ll give you new wood,” he calmly said to the woodworkers, the vapors of his breath giving the words added weight. As amazed as they were, and it wouldn’t be wrong to assume that they thought he wasn’t in his right mind, they agreed. Dwarika, at this point in life, could afford to replace the pillar. It was an expenditure his father would never have approved of in decades past.

The Father

The Father

Janak Das Shrestha was a product of the early part of the last century. His childhood was far from normal: at a young age, he lost his mother. Then an uncaring father and, later, an apathetic stepmother didn’t make life any easier. With the one person who could have stood as a pillar of support gone, the young boy was left to fend for himself. But what could a child do? The life he led was hollow. No amount of stitching could stop his clothes from falling apart, to hunger he was no stranger, and despair was a familiar feeling. Fortunately, the young Janak’s plight was noticed by his father’s mit(ritual friend) who insisted on the boy being placed in the care of Janak’s childless aunt.

By the time he was 13, Janak had started his own business, a shop in the house he inherited from his father who had passed away by then. The place was in Makhan Tole, a crowded business street in inner Kathmandu, which, at one time, was the departure point of the main caravan route to Tibet. Here, amidst the din and the chaos that are signs of a successful marketplace, Janak ran House Pasal, selling imported cigarettes and Barratts shoes. At 17 he married 13-year-old Kanchhi Maiya. Makhan might have been the main street of the city during that era, but House Pasal wasn’t doing very well. “My mother used to say he had nothing when she moved in,” recalls Bina Pradhan, their only daughter.

Hardship had drilled into Janak, fierce independence and pride. His uncle, the husband of the aunt who had raised him, had brought in another wife. The man was afraid Janak and his aunt would lay claim to his property, leaving his second wife and their children out in the cold. Lying on his deathbed, Janak’s uncle asked him to sign a paper that relinquished their rights to the property. Janak refused. “I don’t want anything to do with your property or your money,” he said coldly, disappointed at the pettiness on display. “I’ll support my aunt on my own.”

But pride and independence do not translate to riches. Janak’s financial situation hadn’t improved even after he had fathered three children, a fact that was a constant bother for his father-in-law, according to Janak’s sixth son, Subarna. Kanchhi Maiya was a member of a prominent Newar family, one with connections to the ruling Rana elite. Her father was Ratna Man Singh, one of four Bada Kajis, a title given to representatives of the people’s governing body during the time of Prime Minister Bhim Shamsher Jang Bahadur Rana. “It was at his insistence that my father was made the sole distribution agent of Morang Cotton Mills,” says Subarna. “Until then, he had steadfastly refused to take advantage of my mother’s connections.” Although defunct today, Morang Cotton Mills was an integral part of Nepal’s history. Along with a few other industries established in Biratnagar between the mid-1930s and the mid-1940s, it played a crucial part in accelerating Nepal’s industrial development.

Janak’s upward mobility due to his position at Morang Cotton Mills was only the start of his climb up the social ladder. With his newfound contacts, he secured the position of jeweler for Prime Minister Bhim Shamsher’s family. He also opened a furniture shop in New Road called Frame Furniture. Soon, he rose up the ranks to be given the title of Battis Kothi Mahajan, an honorific given to a select group of prominent traders. Janak was also a founding member of the Nepal Chamber of Commerce and served as its sixth president from 1961-62. Later, he was awarded the Gorkha Dakshin Bahu by King Mahendra for his contributions to business and commerce. In 1956, during the coronation of King Mahendra, Janak even had the honor of being a part of the royal elephant procession, amidst esteemed guests such as the Earl of Scarborough and Chinese Deputy Premier Ulan Fu.

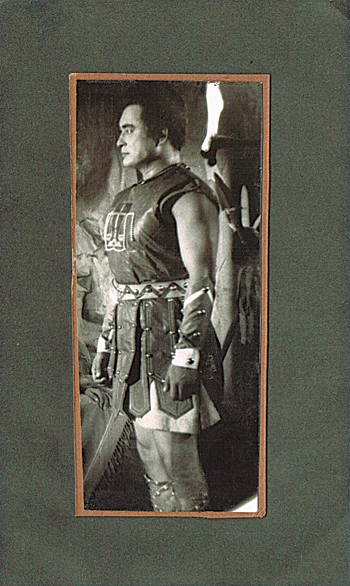

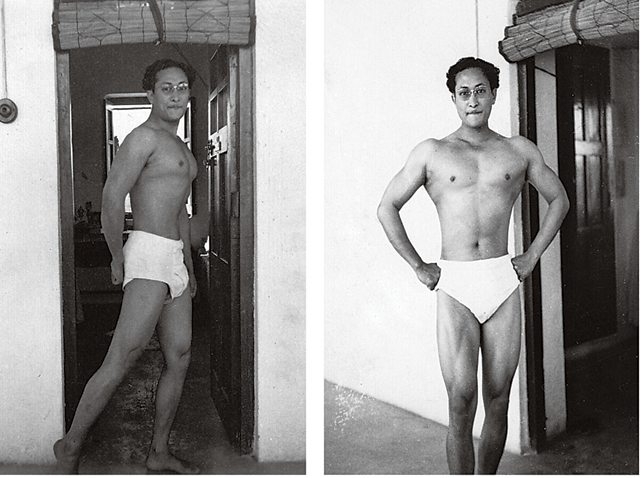

Dwarika picked up the ancient pillar effortlessly. In his early-30s, the former ‘Mr. Banaras Hindu University’ of 1947 was fit; he had been working out daily with the youngsters of the Youth League, a group he had recently founded. But to get the relic home, he would need help. So he called out to a waiting porter in the authoritarian tone of his, an intonation he had cultivated early in life. He had to if he wanted to be obeyed. As Dwarika watched the lithe man, clad in a thin sweater and daura suruwal—clothes that belied the winter chill—pick up the pillar, his eyes hovered across the square for instances of similar destruction. Satisfied with not finding anything comparable, he headed home, the porter following close behind.

Dwarika picked up the ancient pillar effortlessly. In his early-30s, the former ‘Mr. Banaras Hindu University’ of 1947 was fit; he had been working out daily with the youngsters of the Youth League, a group he had recently founded. But to get the relic home, he would need help. So he called out to a waiting porter in the authoritarian tone of his, an intonation he had cultivated early in life. He had to if he wanted to be obeyed. As Dwarika watched the lithe man, clad in a thin sweater and daura suruwal—clothes that belied the winter chill—pick up the pillar, his eyes hovered across the square for instances of similar destruction. Satisfied with not finding anything comparable, he headed home, the porter following close behind.

Dwarika Das had stayed busy since arriving home from Banaras. One of his first ventures was putting together the Youth League or Yuva Sangh in 1951, the first of its kind in the country. The Rana regime had fallen, but the citizens, so long repressed, were yet to recover. Dwarika noticed that the youth were lacking—socially and in terms of education—compared to their Indian counterparts. Seeing their general disregard for health, and an ignorance of worldly affairs, he decided it was time to bring them up to speed.With the establishment of the League, Dwarika wanted to help the youth become physically and mentally sound, one of the reasons why the group of men held exercise sessions every morning at Tundikhel.

It was Dwarika’s work with the Youth League that prompted Bahadur Shamsher Rana, a prominent general of that time, to donate four ropanis of land to him, which he decided to put into a trust. This plot, located in Jyatha, Thamel, was where Nepal Byayam Mandir, Nepal’s first gym, was established in 1953.The grounds, till then, had been used by a Jyapu farmer. Dwarika, in a fit of proactivity, called upon the League members and together they dug the foundation for the gym structure themselves.

Internal tensions

Dwarika’s return to Kathmandu led to frequent personality clashes between father and son. It was bound to happen. The two belonged to different generations, and that meant they didn’t see eye to eye on many things. As Bina recalls, her brother had become progressive, while their father was insistent on retaining traditions of old.

There comes a time in every man’s life when he realizes the need to be his own master. Knowing that the only way he could be free was by branching out on his own, Dwarika decided to open a hotel in New Road. But this was the early 1950s. Nepal was free of the shackles of Rana rule but not of the close-mindedness that defined those times. His decision to start a hotel was met with vehement objection from the family—his maternal grandfather in particular. For them, it was taint to the family name. “Do you want to sell food for a living? What’s the difference between you and a butcher?” they asked him. Frustrated with the attitude of his elders, Dwarika remained silent, but he was devising a plan to placate them. “What if I used the word ‘inn’ instead of ‘hotel’?” he asked. “A hotel serves meals but an inn honors its guests,” he explained. The plan worked. Paras Inn was established in 1951, one of the first hotels in Nepal. It became a landmark, and was a popular hub from its inception until the 1970s. It was here that pilgrims, pilots, and businessmen from India stayed, while prominent politicians of that time—such as BP Koirala and Krishna Prasad Bhattarai—arrived every evening for a cup of tea. Within a few years, the establishment had been successful enough for Dwarika to rename it Paras Hotel. This time there were no objections.

Walking away from Basantapur, Dwarika wondered about the ancient windows and pillars that had already met a fiery fate. Kathmandu, after a century of Rana rule, was opening up to modernity, and that term, to most, meant concrete houses. Dwarika, wondering why he hadn’t noticed it earlier, realized that the Valley’s culture had not been understood, and that the same ignorance was contributing to its destruction. Deep in thought, nodding to the people he passed out of habit, he wondered what could be done to preserve Kathmandu’s architecture, its heritage. He needed someone close to help him, and the first person that came to mind was his brother, Mathura.

The Brother

Dwarika had seven brothers and the one he got along with most was Mathura, the closest to him in age.

Born in 1928, Mathura, like his father, did not have a normal childhood, except in his case it had to do with the alignment of the stars. He was born on what was considered an inauspicious date, and was thus sent to live with his maternal uncle. By 18, he was back home and ready to join his brother in Banaras. However, like most people in those days, Mathura had married early and his father wanted him to get involved in the family business. Mathura wanted none of it, though. He had grown up freely in his uncle’s house, dotingly looked after by his grandmother. His father was not going to hold him back. One night, he quietly slipped out and headed towards Banaras. There, he completed his matriculation, then joined Banaras Hindu University, just like his brother. He even took up bodybuilding and went on to become Mr. BHU in 1955, exactly like Dwarika had done eight years earlier.

Mathura continued bodybuilding after returning to Kathmandu, even going on to represent Nepal in the Third International Youth Games in Moscow in 1957. He was all set to take part in the bodybuilding and weightlifting categories, and led the Nepali contingent during the opening ceremony. But, as luck would have it, he was unable to participate due to a sudden illness.

On his return, Mathura saw few prospects in the family business. He then set his eyes south towards Bombay for a career in films. It was a decision that did not go down well with his family.

Dwarika’s thoughts were suddenly broken when he noticed the porter was no longer following him. Turning back, he saw the man a few meters away, struggling to ignite a cheap filter-less cigarette while sitting on the pillar. Dwarika was a fair employer but he was also strict. He did not suffer idlers gladly. He calmly walked up to the man, gave him a hard pat on the head, and ordered him to get up. The porter was on his feet before the sentence was even completed, the smell of tobacco and guilt hanging around him like a cloud.

Dwarika had married young, but his wife had been sickly and undernourished. She had succumbed to tuberculosis, leaving behind a son. In 1955, he remarried. His second wife was Ambica, a convent-educated young woman, who he first met in Kalimpong.

Although Dwarika had found relative success on his own, with the hotel and his high post in the government, he still lived with his parents. The tensions with his father that had first surfaced when he returned from Banaras continued. As Ambica recalls, Dwarika wanted the women of his family to be educated and their health looked after but his parents were too conservative in their outlook to agree.

Bogged down by the stress of his job and problems at home, he left the family house early one morning in 1956, taking along Ambica and their year-old daughter, Sangita. Such a move was unheard of in that era, and what followed was years of hurt. The young family rented the house of a friend before saving and taking out bank loans to buy nine ropanis of land in Battisputali. The land belonged to a Rana, a wife-beating drunk who had fallen on hard times due to his drinking habit. Despite having already received payment, the man refused to leave. In a drunken stupor he challenged the person who had bought his land to a fight. As Dwarika’s bulky, barrel-chested frame entered the shadow of his crumbling house, the former owner of the plot fell silent.

Thus were sown the seeds of the Kathmandu Village Resort, today known as Dwarika’s Hotel.

Dwarika stooped down to enter the low doorway of his ancestral home in Makhan. The marketplace around the house was starting to show signs of life. Gesturing to the porter, he pointed towards a spot under the old stairs where he wanted the pillar placed. A younger sibling came by, looked at what he had brought in, shrugged it off, and ran towards whatever the next distraction was, in that hurried way children do.

Dwarika paid the porter, who then disappeared without any sort of acknowledgment. It was then that he was struck by a thought he hadn’t considered: Would his father think he was crazy to have wasted money on what he probably thought was a worthless old pillar?

Epilogue: 1991

As Dwarika looked upon what he had created, he was filled with pride. The Kathmandu that he knew and loved was being replaced, but his plan to produce a 15th century environment in the middle of a modern city was coming to fruition. But there was still a lot more to be done. In the winter of his life, he knew deep inside that he wouldn’t be able to see the completion of his hotel, but he could rest easy knowing that he was leaving his life’s work in good hands—his wife and daughter were more than capable of bringing to life what he had visualized. He had continually sketched plans, some very complex, and they would carry it out exactly the way he wanted. He knew what he had achieved would have been impossible if his parents hadn’t forced upon him the weight of responsibility.

In the four decades that had passed since he first picked up that pillar, there had been mighty highs and heavy lows. Dwarika looked back on the death of his son. The tears had dried up and the memories dimmed, but the hurt remained. Pawan, the last vestige of his first marriage, had suffered an untimely death. He recalled that terrible night in 1972 when he received the message that brought him to his knees. His son had only been 24 when he crashed his 65cc Honda motorcycle into an army truck—numbered 220—at the stretch between Gaushala and Ratopul. It had been a case of sheer negligence; the truck had only one headlight on, and Pawan had mistaken it for another motorcycle. Still, in his own way, Pawan had managed to contribute to his father’s legacy. A talented artist who excelled in charcoal sketches, he had drawn the logo of Kathmandu Travels, a travel agency Dwarika had established in 1969.

He also thought about his brother Mathura’s failed film career. Around 30 years ago, their relationship had passed through a rough patch because he hadn’t responded well to his younger brother’s plans to move to Bombay. But how could he? At that time, actors hadn’t been considered respectable people, and there was no way he would have encouraged his brother to stoop to that level. Nonetheless, he had been disappointed when the film Mathura had worked so hard on had been unsuccessful. His brother had been the first Nepali to write, direct, and act in a Hindi film. But Pahadi Jawan, which released in 1964, failed; it ran only for a day at Ranjana Cinema.Although Dwarika had not witnessed it himself, he knew people made fun of Mathura behind his back, mockingly calling him Pahadi Jawan. Mathura, naturally, had not taken it well, but all was fine between the brothers now. They had reconciled, and Mathura, as he had hoped, had been a great help in the making of Dwarika’s. He had even started a hotel of his own in the busy thoroughfare of Teku, which he lovingly named after their father.

Dwarika had been ridiculed and called crazy when he had started collecting the old carved pillars and windows.His parents had certainly not understood what he intended to do. He chuckled recalling an incident that had taken place decades ago when he had just built his new home. He had placed an old carved window in his living room, which his visiting uncle had found strange. “If you were so short on money, I would have lent you some for new windows,” he had said. All of that was in the past now. People had finally recognized the value of his obsession. The broken down ornate pillars and windows that he bought were restored, and in the process, so was the traditional Newari art of carving, which had been in its death throes then. The old pillars and windows he had so painstakingly collected over the years were now considered national treasures.

As Dwarika gazed upon the recently completed Ram Palace structure in the hotel complex for th

umpteenth time, he drew a long breath. His lungs filled with air and pride, it was at that moment that he knew, for certain, that he’d done it--his life’s work would prove invaluable for the country and the culture he held so dear.

Old photos courtesy: Bina Pradhan, Dwarika Das Shrestha's younger sister .