A chance invitation to a Newar home provides a journey back in time to a different Nepali era.

Imagine yourself taking a walk around Tundikhel in Kathmandu on a warm winter’s day. The air is filled with the sound of birds chirping, a clock strikes eight in the distance. You can smell the trees and the earth, still damp from the morning’s dew. The only sign of traffic is a young man on a bicycle peddling his way to work. Before you, the green expanse of Tundikhel, where Nepal’s former royalty liked to observe the nation’s various festivals, fills you with a sense of grandeur as the historic Dharahara tower, built by one time Prime Minister Bhimsen Thapa (it is sometimes called ‘Bhimsen’s Folly’), looms over you. Behind the field, you see hills and behind them majestic snow-capped mountains. The sight makes you feel good about everything. You take a long breath and as the fresh air seemingly expands your lungs, you feel rejuvenated. But, stop...

Today, the same walk today will leave you quite literally breathless for a far different reason (from pollution). That first description was the Kathmandu of the fifties and sixties. Nepal had only just opened up to the world and people who had heard of this romantic, utopian land started coming up. All that is nothing but a dream today, an old man’s memory at best. That was the Kathmandu people loved to be in, to visit, to make a home of, not for work but because the natural beauty and cultural heritage of Kathmandu is breathtaking.

Born in the early eighties, I missed out on actually experiencing a lot of this beauty, though I have often heard about it around the dining table from my parents. A chance visit to the Chitrakar home near the temple of Bhimsenthan in Kathmandu, a few minutes’ walk from the Basantapur Durbar Square towards Tahachal, became my unlikely passage into that almost mythic valley of yesteryear.

The name Chitrakar is a term that was coined early on in Nepal for the caste of people who made a living as artists. (Chitra is a work of art, a painting.) The ground floor of the Chitrakar residence houses the Ganesh Color Lab, established by Kiran Chitrakar’s grandfather, Dirgha Man Chitrakar. The lab was originally in their old house, the country’s first photo developing studio. A hole bored into the roof of their old house in Bhimsenthan (different from the present Chitrakar residence) served as the source of light. Dirgha Man is the son of Laxmi Lal, a renowned painter of his times. Prior to starting work for the royal family as royal painter and court photographer, Dirgha Man was involved with traditional art forms such as scroll paintings, religious paintings and decorating important religious places, a customary practice of the Chitrakars. When the then Prime Minister Chandra Shumsher Rana set a trip to England and France in 1908, Dirgha Man was allowed to accompany him. The trip gave Dirgha Man a rare opportunity to compose paintings of the picturesque cities of Europe and also to study European art. The succeeding Prime Ministers, Bhim Shumsher and Juddha Shumsher J.B. Rana kept a large part of Dirgha Man’s apparatus within the confines of the Singh Durbar where Dirgha Man worked until formally retiring at the age of 71.

The name Chitrakar is a term that was coined early on in Nepal for the caste of people who made a living as artists. (Chitra is a work of art, a painting.) The ground floor of the Chitrakar residence houses the Ganesh Color Lab, established by Kiran Chitrakar’s grandfather, Dirgha Man Chitrakar. The lab was originally in their old house, the country’s first photo developing studio. A hole bored into the roof of their old house in Bhimsenthan (different from the present Chitrakar residence) served as the source of light. Dirgha Man is the son of Laxmi Lal, a renowned painter of his times. Prior to starting work for the royal family as royal painter and court photographer, Dirgha Man was involved with traditional art forms such as scroll paintings, religious paintings and decorating important religious places, a customary practice of the Chitrakars. When the then Prime Minister Chandra Shumsher Rana set a trip to England and France in 1908, Dirgha Man was allowed to accompany him. The trip gave Dirgha Man a rare opportunity to compose paintings of the picturesque cities of Europe and also to study European art. The succeeding Prime Ministers, Bhim Shumsher and Juddha Shumsher J.B. Rana kept a large part of Dirgha Man’s apparatus within the confines of the Singh Durbar where Dirgha Man worked until formally retiring at the age of 71.

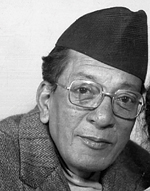

Dirgha Man’s son Ganesh Man Chitrakar learnt the art of photography besides painting from his father. Ganesh Man too followed into his father’s footsteps at Singh Durbar, as a royal painter and court photographer. Ganesh Man is credited as being the first to take aerial photographs of the Kathmandu Valley in 1965 A.D and also as the first person to develop color slides in Nepal. Ganesh Man’s cameras are still in possession of his son, Kiran Chitrakar, also a court photographer who has accompanied King Birendra on royal visits abroad besides other official trips with dignitaries. Kiran today besides working as a photographer works at the state television channel’s office and is working towards opening a museum to preserve the trove of history that is both, his heritage and responsibility.

Dirgha Man’s son Ganesh Man Chitrakar learnt the art of photography besides painting from his father. Ganesh Man too followed into his father’s footsteps at Singh Durbar, as a royal painter and court photographer. Ganesh Man is credited as being the first to take aerial photographs of the Kathmandu Valley in 1965 A.D and also as the first person to develop color slides in Nepal. Ganesh Man’s cameras are still in possession of his son, Kiran Chitrakar, also a court photographer who has accompanied King Birendra on royal visits abroad besides other official trips with dignitaries. Kiran today besides working as a photographer works at the state television channel’s office and is working towards opening a museum to preserve the trove of history that is both, his heritage and responsibility.

“I would have donated the cameras and numerous artworks that belonged to my father and grandfather readily to the government if I trusted them in being competent enough to conserve it. But look at the condition of the present museums in Nepal being look after by the government,” says Kiran of his wish to allow the public to view a piece of history through his family’s possessions. Kiran is of the sentiment that such art cannot belong to a particular person and the public have a right to it as much as he does. But Kathmandu’s earthquake prone nature and the lack of any agency showing interest in providing a premise to portray this art has stalled Kiran’s plans for the moment.

“I would have donated the cameras and numerous artworks that belonged to my father and grandfather readily to the government if I trusted them in being competent enough to conserve it. But look at the condition of the present museums in Nepal being look after by the government,” says Kiran of his wish to allow the public to view a piece of history through his family’s possessions. Kiran is of the sentiment that such art cannot belong to a particular person and the public have a right to it as much as he does. But Kathmandu’s earthquake prone nature and the lack of any agency showing interest in providing a premise to portray this art has stalled Kiran’s plans for the moment.

Three of the cameras used by Dirgha Man are prized possessions of the Chitrakar family today, souvenirs of the family’s rich artistic history. They are i) the American R.B. Graflex, patented on June 1, 1927 by the former Graflex Corporation of Rochester with a Cooks Anastigmat Lens no. 21674, 6 ½”, 165 mm, f/25 ii) the British Camper made by Houhtons Ltd of London with a CP Goerz lens and accessories from Altrincham Thronton Pickard and iii) a camera with a German lens produced by Hugo Meyer & Co., no. 464181. Aristoplanat 1:7.7, foc 17 ¾”. Ganesh Man used 1) Rolleiflex, Rollei, Franke & Heidecke of Braunschweig, Germany 2) Rolleicord, Rollei, Franke & Heidecke and 3) Ikonta M. Prontor-SV, No. 1231/1. Zeiss-Ikon of Stuttgart, Germany.

Pictures that speak

Pictures that speak

Brushing away the dust on the cameras stored inside a glass case alongside framed pictures of his grandfather, father and himself amongst royalty and foreign dignitaries, Kiran says he would not mind displaying the photographs and antique cameras to serious enthusiasts. But one can perceive from the way he looks at and explains certain photographs that he has a deep connection with his inheritance. Kiran is not one to sell his inheritance for a quick buck.

If not anything, Kiran Chitrakar has worked towards uplifting his family’s name. A winner of several medals including the 3rd SAARC Summit Medal in 1987 and Relief for Natural Disaster Medal in 1988, Kiran has covered national and international news and toured the world with the Heads of states. He has held exhibitions of his family’s and his own work in numerous countries such as France, England, Japan, USA, Switzerland and Sri Lanka.

If not anything, Kiran Chitrakar has worked towards uplifting his family’s name. A winner of several medals including the 3rd SAARC Summit Medal in 1987 and Relief for Natural Disaster Medal in 1988, Kiran has covered national and international news and toured the world with the Heads of states. He has held exhibitions of his family’s and his own work in numerous countries such as France, England, Japan, USA, Switzerland and Sri Lanka.

Talk however, eventually returns to the photographs, simply because you cannot ignore them in the Chitrakars’ living room. They are everywhere you look! Transfixed on these timepieces, my mind wanders quite naturally to the years I thought I had missed out on. Temples, people in traditional Newari clothes, a Jyapu man carrying a kharpan on which he carries his trading commodities, children playing in open spaces, landscapes of spaces that are today covered by a concrete jungle - nothing resembles the Kathmandu we see today. Kiran explains one particular picture of his grandfather, the only one he has that was taken by someone in a train station in Marseilles in Paris. The shot has been captured from the side and it shows a crowd of Nepalese in their traditional attire crouching on the streets. “The Nepalese as we know can get a little fanatic about their values. Because the French were known to eat beef, the water there was deemed impure for the Nepalese to drink. So the entourage of people that accompanied Chandra Shumsher carried 300 ghaitos (traditional copper alloy vessel used for carrying water) of water from Nepal to France!” exclaims Kiran, a smile finally breaking on his face.

Amongst the pictures Kiran generously offers to show me are really classic old black and white ones that show Nepal’s former kings and Prime Ministers busy at their favorite hobby - hunting. There are also some amazing inside shots of old palaces that no one else has today and without which one simply would never have a clue as to how the palaces of the country’s formative years looked. The black and white adds a healthy dose of nostalgia. Monochrome tends to blend people in a lot of times but in group pictures of royalty and commoners, the royalty still stands out, with their posture, their attire and the stern, proud look on their faces; the origins perhaps of the great and growing divide between the rich and the poor in Nepal. Other pictures in Kiran’s living room speak of his long-standing relationship to Nepali’s former royalty. Because of his grandfather and father’s close ties to the palace, Kiran too was very close to former royals. Pictures of him with royalty, local and foreign dignitaries fill entire walls.

Amongst the pictures Kiran generously offers to show me are really classic old black and white ones that show Nepal’s former kings and Prime Ministers busy at their favorite hobby - hunting. There are also some amazing inside shots of old palaces that no one else has today and without which one simply would never have a clue as to how the palaces of the country’s formative years looked. The black and white adds a healthy dose of nostalgia. Monochrome tends to blend people in a lot of times but in group pictures of royalty and commoners, the royalty still stands out, with their posture, their attire and the stern, proud look on their faces; the origins perhaps of the great and growing divide between the rich and the poor in Nepal. Other pictures in Kiran’s living room speak of his long-standing relationship to Nepali’s former royalty. Because of his grandfather and father’s close ties to the palace, Kiran too was very close to former royals. Pictures of him with royalty, local and foreign dignitaries fill entire walls.

For a Nepali person, the pictures tend to induce a feeling of pride, of belonging, of a connection that suddenly becomes evident through everything. These pictures should be quite easily the most honest depiction of the country. Mixed in with the flamboyance of the Rana regime, the hunting trips with dignitaries, the extravagant clothes and jewelry is the country’s heart rending poverty, its culture and an unspoiled beauty that is almost sad since the observer now knows that Kathmandu and a lot of what we see of Nepal has changed drastically.

For a Nepali person, the pictures tend to induce a feeling of pride, of belonging, of a connection that suddenly becomes evident through everything. These pictures should be quite easily the most honest depiction of the country. Mixed in with the flamboyance of the Rana regime, the hunting trips with dignitaries, the extravagant clothes and jewelry is the country’s heart rending poverty, its culture and an unspoiled beauty that is almost sad since the observer now knows that Kathmandu and a lot of what we see of Nepal has changed drastically.

For the foreign eye, the pictures are a visual treat. More than a portrayal of the photographer’s talent at his vocation, it is a stripped down look at what Nepal looked like outside the frame of postcards. Because more often than not, the pictures seem flawed by showing a little of what was not meant to be in the frame. This is the very quality that lets the Chitrakars’ pictures stand apart. For people who live here, there are quite a lot of ways to connect to Nepal’s heritage but for those of you who are just passing by; these pictures will paint you a better picture of where you have been.

For the foreign eye, the pictures are a visual treat. More than a portrayal of the photographer’s talent at his vocation, it is a stripped down look at what Nepal looked like outside the frame of postcards. Because more often than not, the pictures seem flawed by showing a little of what was not meant to be in the frame. This is the very quality that lets the Chitrakars’ pictures stand apart. For people who live here, there are quite a lot of ways to connect to Nepal’s heritage but for those of you who are just passing by; these pictures will paint you a better picture of where you have been.

Note: Many thanks to Mr. Kiran Chitrakar for graciously inviting and introducing the writer to his family and his family history.