After the must-sees and must-dos in Pokhara: From visiting Mahendra Gufa to boating on Phewa, or a jump from the top of Sarangkot on a Para-glider to zip flying (fastest, steepest and longest in the world), hurtling down at 140 km plus to send your adrenalin pumping like mad, it seems the only thing left to do for a holiday maker is to hang out in the chic touristy lake front, kill time gazing out over the serene lake from a terrace restaurant—and guzzle beer.

Hang on … the ‘Lake City’ still holds a surprise for you. Go exploring the river Seti (white river) as it winds its course right through the city core. The mystery deepens when the wide boisterous river enters dark gaping holes in the face of hills—and vanishes. You are left open-mouthed, disbelieving—and out of your depths. And then after a brief journey into the unknown, the Seti dramatically reappears. It’s magic.

The glacier-fed river Seti (Gandaki) that has dug deep subterranean tunnels into the city has long since mystified the people of Pokhara. The local elders believe and fear that the entire city floats on the waters of the Seti. Porous underground, a maze of caves and chasms, the Seti water flowing more than 50m, deepest 80m, below the street level, is something of a geological enigma, which has led to this local myth.

“An entire truck, parked in a street a night before at Archal Bot (near the Bindyabasini temple) sank into a cavernous pit, literally buried, the next morning. That happened some four years ago”, says Purna Bahadur Jwarchan, an environment engineer from New Road, Pokhara. “Cases of such subsidence have been recurrent in and around the city, some alarming. Few come to notice but most go unreported”, adds Jwarchan(Jwarchans are ethnic Thakalis from Marpha, Mustang).

The findings made by the Chinese contractors during construction of the Nayapul(literally new bridge), near Prithivi Chowk, were no less alarming.

The Seti had scoured out hollow spaces on its sides as deep as 250m at some places. “Statistics show that Pokhara has the highest precipitation (3,350 to 5,600mm/year) in the country. But even the heaviest rainfall doesn’t lend the Pokhara streets waterlogged for the water gets sucked below ground in no time”, Jwarchan adds.

The Seti had scoured out hollow spaces on its sides as deep as 250m at some places. “Statistics show that Pokhara has the highest precipitation (3,350 to 5,600mm/year) in the country. But even the heaviest rainfall doesn’t lend the Pokhara streets waterlogged for the water gets sucked below ground in no time”, Jwarchan adds.

Geologists believe that the Pokhara valley is nothing but gravel mass filling brought down by the catastrophic Seti flash floods, triggered off by an earthquake in the high Machapuchare and Annapurna region. In its wake, the river is also said to have worked up extensive terraces, lakes (seven), caves and gorges in the valley.

And there is GLOF (Glacial Lake Outbursts Floods) to consider. A GLOF is said to have occurred 450 years ago with an area of 10km2 located behind the Machhapuchare , an ice-cored moraine collapse that brought down 50-60m thick debris into the Pokhara basin( Ref: T. Yamada & C.K. Sharma).

Referring to the disastrous Seti floods of May2012, Kunda Dixit writes: “The Seti has seen much bigger floods in its history, one of them occurring about 800 years ago, which was of biblical proportions and brought down a wall of debris 100m high to what is now Pokhara city”.

The trail of the Seti gorge is best explored on foot or on a bicycle, better still on two wheels as you can cover more ground in less time. Mountain bikes can be hired from quite a number of shops at the lake side (try Hallan Chowk). The asking price for the day at rupees 800 to 1000 may vary between shops; I got one for 700—it took a mulish haggling though.

The trail of the Seti gorge is best explored on foot or on a bicycle, better still on two wheels as you can cover more ground in less time. Mountain bikes can be hired from quite a number of shops at the lake side (try Hallan Chowk). The asking price for the day at rupees 800 to 1000 may vary between shops; I got one for 700—it took a mulish haggling though.

Don’t forget to ask for a helmet, a bicycle lock and a hand pump, included in the price. And if you can manage, carry a raincoat—just in case. I wouldn’t be surprised if you get caught up in one of the vagaries of Pokhara weather. I was. It was sunny, way too warm, when I started but the afternoon suddenly took a mood swing—first it was a dust storm and then a lashing downpour. Apparently, as unpredictable as the Seti, the weather of Pokhara can be notoriously fickle, anytime—it’s anybody’s guess.

All set? If you want to make a good start, begin from the beginning. First ride to Mahendra Pul(bridge), located in the downtown part of the city, crowded but fascinating as the old bazaar hub, which it still is. It takes 25-30 minutes from Mahendra Pul to the K.I. Singh Bridge—the river mouth where the Seti makes it first entry into a dark narrow crevice in a rocky outcrop.

I bicycle around Kathmandu quite often and every time I hit the streets, I get the gut feeling that I’m going to get knocked down either by a speeding microbus giving chase to another, a cab in feverish haste to drop off a passenger, pick another, or a reckless motor-biker trying to beat the clock.

With no traffic stress, no obnoxious honking, and none of the choking exhaust fumes and dust (the latest scourge brought down by the road-expansion in Kathmandu), you feel an incredible sense of relief once you land in Pokhara. Cycling? It’s like riding in your own backyard!

With no traffic stress, no obnoxious honking, and none of the choking exhaust fumes and dust (the latest scourge brought down by the road-expansion in Kathmandu), you feel an incredible sense of relief once you land in Pokhara. Cycling? It’s like riding in your own backyard!

As you leisurely pedal by Bhimsen Tole (street) to Bindyabasini( a Hindu shrine dedicated to Goddess Bhagwati located on top of a wooded knoll), much revered by the Pokhrelis(people of Pokhara), you will notice between rows of modern houses some very old ones too—reminding you that the street must have been once an old locality.

So it was; history of Pokhara has it. Highly impressed by Kathmandu valley’s culturally rich and ornate architecture, in 1752 AD, the King of Kaski (then a Chaubise Rajya: a principality; now a district with Pokhara as headquarters) decided to invite ethnic Newar craftsmen and artisans from the Nepal Valley, cities of Kathmandu, Patan and Bhaktapur. Most went back but some took up permanent residence in Bhimsen Tole. Although languishing in obscurity and neglect amid burgeoning concrete structures, a handful of these old houses still retains the last vestiges of the borrowed Newari heritage and craftsmanship.

Streets (in late June) mostly lined by shops and few eateries, appear half-empty, with businesses in a relaxed ambience. Keep an eye open for children and dogs however, which might dart across the road, unawares. In a few moments you will reach the uptown bazaar called Bagar. From there, it’s just spitting distance to the K.I. Singh Bridge. Right next to the bridge, an entrance gate reads: Seti Gorge, K.I. Singh Pool (bridge). A five rupee ticket will let you in.

As you take the flight of steps down a small park with benches around, the deep rumble of the gushing water reaches your ears. A roughly 15m long bridge spans the gorge; an irrigation canal runs right through the middle of the bridge and enters a tunnel before disappearing into the wooded hillside.

You can peer down from the bridge on both sides for a giddying view. With overhanging brush, the steep side walls slide down some 40m into a gully of rushing water that looks like milk being churned to make butter. Incredulous, you can’t help wondering how come the river so big and wide only a few hundred meters north could squeeze through that crack a little over a meter wide—and disappear into the hills.

Try next the Prithivi Narayan Campus, hardly ten minutes away from the bridge. As you go around the back of the campus premises, a complete change of scenery appears before your eyes—beautiful, if not spectacular.

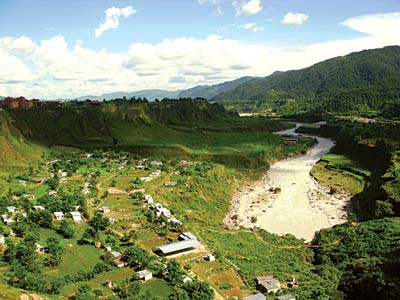

The Seti that disappears into a rocky cleft at the K.I. Singh Bridge exits here at the base of a hill into an almost 400m wide canyon. More than 100m high embankments tower over the river. From the ridge, you can see way down a rivulet, Kali, which joins Seti at the foot of a hill as the towering Kahun Danda(hill) soars into the eastern skies. On the other side of the ridge across a suspension bridge, you can make out a cluster of buildings: the Manipal Hospital.

Now, a little adventure! You need to dismount and walk your bike—and lug it too briefly (like I did) for the single track twists and turns sharply down to the suspension bridge. “That was tricky”, you’ll say to yourself later, enjoying however the little exercise all the same. After crossing the bridge a paved road parallel to the hospital’s compound goes north—follow it. Some 10 minutes will bring you to a fork. Take the stony dirt road that goes down to the Seti-Kali confluence.

If the Seti (in late June) water looked like milk coffee, the lesser Kali, which could be waded through, appeared light blue. The rivulet appeared busy: Men bathed; women washed clothes and kids frolicked in the cool clear water. The Seti surged out of a cavernous hole in the face of a hill with overhanging brush. Looking like the mouth of a cave, it reminded me of an entrance to my childhood comic hero, Phantom’s den. Now, you wouldn’t like to miss taking a few photographs after all the trouble.

Pedal back the road you came, and instead of turning left towards the hospital take the right one, a dirt road along the Seti embankment that goes to a place called Fulbari. After having continued south for a kilometer through a wide canyon, the Seti here confronts again a wooded cliff. A flight of steps takes you down to the river but care should be taken as it’s steep and could possibly be slippery. The opening in the hill resembles the one at the Seti-Kali confluence. A Narayan temple stands high up on the opposite embankment. The river disappears again into the hill with an intimidating roar.

Next head back to the bustling Mahendra Pul(bridge), 20 minutes away. Here, most visitors to Pokhara get their first glimpse of the narrow Seti gorge. As you peer down to look at the Seti, you’ll shake your head and snort like an enraged bull, apparently disapproving of the piles of filth dumped in there.

Next—Ramghat , the cremation grounds of Pokhrelis. Take the road that goes west from Mahendrapul, past a Ram temple; if confused, ask around. For the third time, you will be crossing a bridge over the narrow gorge. Here the Seti exits the fissure and bursts out into an amazingly wide expanse with vast sand banks while high embankments flank the river; Ramghat is on the other side of the canyon.

Follow the slope past houses and some greenery that extends down to the high embankment of the Seti. You can see the river on your right as you free-wheel down the paved road. After something like one-half kilometer, take a right curve to arrive at a hospital. A gravel road on your right goes down to Ramghat.

The Seti can be a frightening spectacle during the monsoon. The river does not follow a strict pattern however, and can turn most unpredictable—and devastating—monsoon or otherwise. Heavy rains, landslides, or snow avalanches in the high Annapurna region trigger off floods even in normally calm months. The havoc and loss of lives caused by the recent Seti flash floods that unexpectedly hit the Pokhara valley in May this year bears testimony to this fact.

At Ramghat, the Seti(late June) was flanked by large sand banks that stretched out to the foot holds of the high embankments. With hordes of sand miners working close to the water, the river looked like a trickle. For the third time the Seti enters the gaping mouth of a hill here. During monsoon, the water level rises and covers almost the entire sand banks.

Take a break, have a refreshing cup of tea, a snack at one of many shops that you will come across. Strike a conversation and the shopkeeper might have some interesting things to tell you about the Seti, or of Pokhara life in general.

After Ramghat catch the highway at Buddha Chowk, onwards towards Prithivi Chowk, the busy intersection that reminds one of Kathmandu’s nasty gridlock. On the way stop by the China Bridge or Naya Pul, as it’s called, and take a look down the narrow gorge.

Now for the final leg, turn left from the Bus Park at Prithivi Chowk and head south on a gravel road into the outskirts. Shortly, the slums begin. Take the left turn that leads down to a wooden bridge over the Seti, passable only for pedestrians and bicycles. With shrubs and dense undergrowth, you could be lucky to see the waters of the Seti down the narrow gorge.

The Seti continues its journey through the chasm, to the southern ramparts of the Pokhara valley. As you proceed on the paved road to Naya Gaun(new town), you will come to another bridge, a vehicular one this time. Take a breather, peer down off the bridge. With newer settlements dotting the landscape, it seems that the pristine farther reaches of southern Pokhara valley have also been encroached.

After something like 20 minutes, you arrive at the IMM (International Mountain Museum), the place called Ratopahire or Gharipatan—a good vantage point that commands a spectacular view in the north of the Machapuchare, the Annapurnas, Manasalu, Lamjung Himal and to the extreme left, the Dhaulagiri. Here, the Seti exits the chasm and can be seen winding its way down between boulders, getting steeper and rockier.

Continue on the paved road on a slope, till you reach Dhunge Sanghu, where the Seti for the last time enters the chasm with a deafening roar. Dhunge Sanghu, literally a stone bridge, may sound a misnomer to you, for the bridge looks nothing but concrete. It used to be but a stone bridge, the locals say.

Dhunge Sanghu makes a compelling view of the river and the surrounding countryside. Being on an elevated land, you can make out the dark outline of the lush wooded gorge from above as craggy walls with undergrowth flank it. The eastern skyline is dominated by a red building of the Fulbari Resort, perched high on a ridge. Some 200m way down you can make out a small bridge that spans the gorge. That’s Sita Paila, beyond that the Seti spreads out into a wide canyon, totally free after this point, as it winds its way south and is lost in between lush green hills.

From Dhunge Sanghu, Sitapaila is about 200 yards, downhill. A shrine of Shiva is located at the high banks of the river that is accessible by stone stairs. Normally, a secluded spot most times of the year, the shrine is thronged by devotees by the thousands on the first day of Magh(Dec-Jan) as the place buzzes from dawn till dusk to celebrate the annual mid-winter mela(fair).

Your adventure ends here. Guess what! You’ll have covered the entire length of Pokhara city, crossed the Seti gorge no less than nine times—and explored nothing short of a mystery trail. It’s time for you to pedal back—happier and wiser. You can round off the trip perhaps with a chilled mug of beer or brewed coffee in a lake front restaurant. Cheers!