Someone came into the room where my cousins and I were getting ready for the ceremony and gave to each one of us a rectangular piece of yellow cloth a little smaller than an A4-size sheet of paper. Strings several inches long were sewn on each corner of this piece. This, we were informed, was our underwear for the day. We were not amused; in fact we were aghast at the size and shape of the thing—at least I was. “I am not wearing a thong,” my eldest cousin said, and he pretty much spoke for all of us. We were having our upanayan that morning. I was eighteen. This last bit of apparel for the day was too much. We would be having our heads shaved and wearing a silly dress in front of dozens of relatives and acquaintances. Wasn’t that enough humiliation for a day? We passed on the something-B.C. design underwear, but we followed every other ritual as directed by the priest.

Most of us who have undergone the Hindu initiation ritual of upanayan, remember it as a day of unprecedented activities. It is meant to be that way, for it is believed that this ceremony marks the beginning of a Hindu male’s life as a member of his society. After the completion of upanayan he has to take on – or at least is thought to be prepared to – new roles and responsibilities. Most of us go ahead with the day and do what we are asked to do. But whether we agree or refuse to do something, most of us don’t question the relevance of the rituals we perform. What is the message behind the routine, archaic, or seemingly absurd acts that need to be performed during upanayan?

Most of us who have undergone the Hindu initiation ritual of upanayan, remember it as a day of unprecedented activities. It is meant to be that way, for it is believed that this ceremony marks the beginning of a Hindu male’s life as a member of his society. After the completion of upanayan he has to take on – or at least is thought to be prepared to – new roles and responsibilities. Most of us go ahead with the day and do what we are asked to do. But whether we agree or refuse to do something, most of us don’t question the relevance of the rituals we perform. What is the message behind the routine, archaic, or seemingly absurd acts that need to be performed during upanayan?

Rudolf Högger’s book The Sacred Thread explores that question. To investigate the hidden meaning of rituals observed during upanayan, he draws from sacred texts, scholarly works, mythology and religious and cultural beliefs. What makes the book especially interesting is his usage of concepts expounded by Carl Gustav Jung to shed light on the psychological aspects of the rituals.

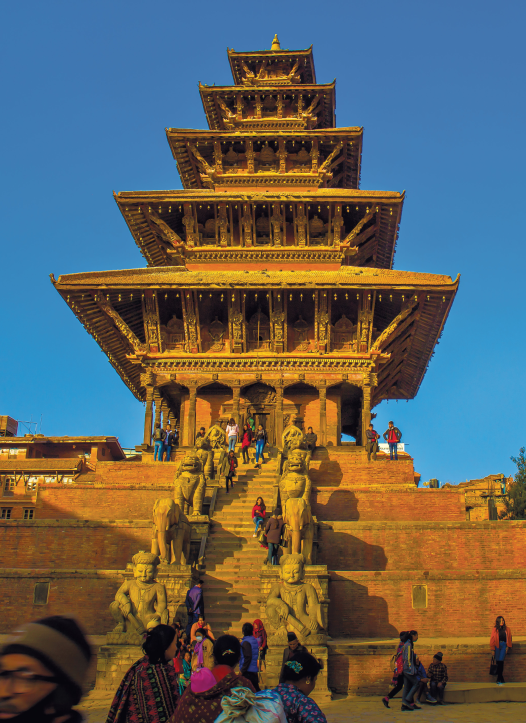

The book is based on Högger’s experience of attending a friend’s son’s upanayan. The author is not just another invitee to the ceremony; he has to play the role of the boy’s mama (maternal uncle). Högger, understandably, is eager to know more about this ceremony’s significance. Even as he assumes the all important role of mama and performs all the tasks it entails, he maintains a researcher’s objectivity and keen observation, minutely examining the events unfolding before him. He delves into the hidden meaning and deeper significance of most things, from objects to the site of the sacrificial fire to the act of changing into new clothes to begging for alms. Rituals are explained citing ancient scriptures like the Upanishads and Vedas. The author also uses Hindu art and architecture to elucidate a point. The conclusions or answers thus attained are then seen through the eyes of a psychologist (the author is a psychologist by training), using C. G. Jung’s concepts of individuation, collective unconscious and archetypes.

“What inner process is being mirrored in such a ritual?” the writer asks himself at one point in the book. It is the question the author attaches to every single ritual performed during the ceremony. The answer to this central and repetitive question, which the writer diligently seeks, results in a deeper understanding of the ritual and, through it, of inner aspects of human life. The writer does not, however, understand these deeper meanings as belonging to any one culture, creed or society alone. On the contrary, he says, “their significance seems to extend beyond any specific religion or creed, and they can be found in the most distant cultures of our globe.” Similarly, the scope of the book, although it illumines a Hindu religious ceremony, is not limited to it. It will be of particular interest to those who have undergone upanayan, but it is equally a work for anyone wishing to better understand the fundamental questions of

human existence.